James Hannaham

James Hannaham

Crawling Broadway, eating the Wall Street Journal: the performance artist gets a MoMA retrospective, and more.

Pope.L, The Great White Way: 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street, 2001–09. Performance. © Pope.L. Courtesy the artists and Mitchell–Innes & Nash.

Pope.L: Instigation, Aspiration, Perspiration, Public Art Fund (curated by Nicholas Baume with Katerina Stathopoulou), September 21, 2019; Museum of Modern Art (curated by Stuart Comer with Danielle A. Jackson), 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through February 1, 2020; Whitney Museum of American Art (curated by Christopher Y. Lew with Ambika Trasi), 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through

March 8, 2020

• • •

“I got my own cultural anorexia,” the performance and visual artist Pope.L (formerly known as William Pope.L) wrote in his 1997 manifesto, “Notes on Crawling Piece,” declaring what he deemed a binge-and-purge relationship to modern art (despite the clinically inaccurate metaphor). “It’s kinda racy, / I get down on my belly and crawl till I’m reality.” This is how Pope.L explains, among other things, his signature works, a series of performances in which he hits the pavement on hands and knees to move down the street—in one case, The Great White Way: 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street (2001–09), he traveled the entire length of Broadway in Manhattan. He’s a scruffy, bespectacled black man, and to scuttle along the pavement he usually dresses in a Superman costume or a cheap suit, lending him the appearance of a civil rights activist gone mad, a homeless person with an agenda, or Cornel West on a really bad day.

Pope. L, How Much is that Nigger in the Window a.k.a Tompkins Square Crawl, 1991. Digital C-print on gold fiber silk paper, 10 × 15 inches. © Pope. L. Courtesy the artists and Mitchell–Innes & Nash.

Despite his unassuming abjection, or maybe because of the tenacity of similar abjection in our culture, and the fact that he has persistently thrown his arte povera in the face of a market obsessed with luxe surfaces, he has bitten off a huge chunk of gallery reality this fall. Under the overarching title Pope.L: Instigation, Aspiration, Perspiration, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Public Art Fund have joined forces to present, respectively, member, a retrospective primarily of Pope.L’s performances; Choir, a fascinating installation in the Whitney’s first-floor project room; and Conquest, a collective live-performance crawl involving about 140 people, which took place on September 21, documented on the Public Art Fund website. Whether this Pope.L smorgasbord constitutes overdue appreciation or institutional co-optation depends on—well, maybe it’s both, and maybe that’s okay. The brother deserves this kind of attention, and he wears it gracefully. Despite ironically dubbing himself the “Friendliest Black Artist in America” years ago, he’s an actual contender.

member: Pope.L, 1978–2001, installation view. © 2019 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

The retrospective entitled member lies nestled in the shiny new MoMA, whose design has moved the institution one step closer to a high-end airport mall in Dubai. (Though member shares its name with a 1996 piece in which Pope.L appeared in Harlem with a white tube protruding from his fly, in this context it may also refer to memory and museum patronage.) The juxtaposition of his oeuvre with MoMA’s opulence is jarring, but not detrimental.

The show commemorates a selection of Pope.L’s performance work from 1978 to 2001 with video installations, props, and photographs, going some way toward integrating his aesthetic into the gallery’s design by removing pieces of drop ceiling and drywall, through which the artist has pledged to peep during periodic visits. For the uninitiated, member represents a fabulous, well-organized opportunity to get to know Pope.L’s work, but it’s hard not to wish that the exhibition had built in more of the artist’s raunchy, scatological gestalt. But, you know, MoMA has pearl-clutchers to please.

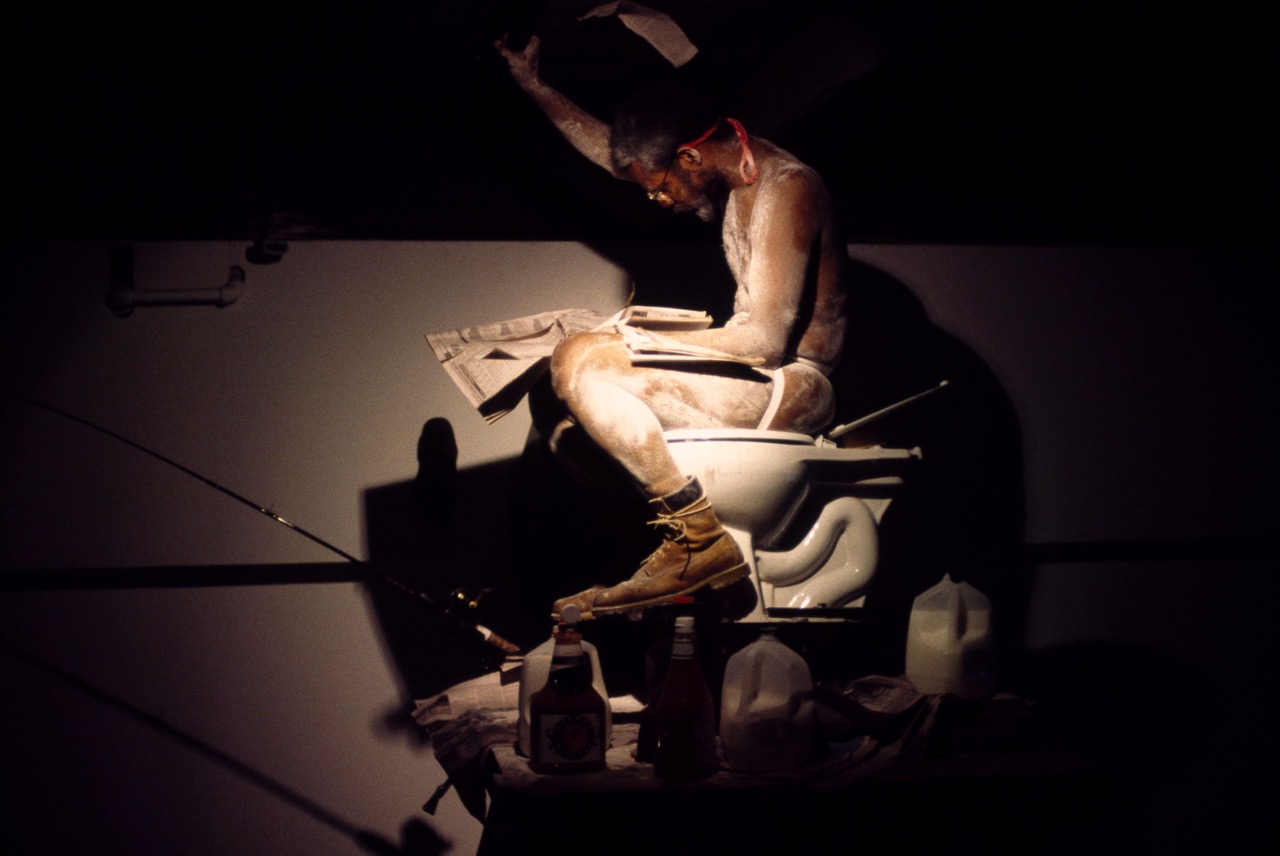

Pope. L, Eating the Wall Street Journal (3rd Version), 2000. Digital C-print on gold fiber silk paper, 6 × 9 inches. © Pope. L. Courtesy the artist and Mitchell–Innes & Nash.

Pope.L’s seemingly simple idea—to crawl as an adult—has lost no relevance during the forty-one years since his first, Times Square Crawl (1978). Sadly, while the racial inequality, income disparity, and erasure of the poor that the piece highlights have gained recognition since the days when crawling down a New York street would get you a palm full of broken glass and a skin disease, they have not exactly improved. But Pope.L’s crawls have perhaps overshadowed other fine work by the artist, including ATM Piece (1997), when Pope.L chained himself to an ATM with a rope made of sausage while wearing a skirt made of dollar bills that he handed to bank visitors, and Eating the Wall Street Journal (3rd Version) (2000), a performance in which Pope.L sat atop a throne-like toilet, consuming and vomiting up the WSJ. The show also includes many drawings, constructions, and artifacts—including that toilet.

Pope.L, Choir, 2019 (installation view). Thousand-gallon plastic water-storage tank, water, drinking fountain, copper pipes, solenoid valves, pumps, MIDI controllers, electronic timer module, level-detection probe, flow meters, programmable logic controller, wood, scrim, vinyl letters, microphones, speakers, wires, and sound. © Pope.L. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Over in the Whitney’s lobby, a soundtrack of echoic drippy water alerts you to the presence of Choir, tucked in the projects room down a little hallway to the right of the elevators and left of the café. In keeping with the marginal status of the space, Pope.L has turned it into something that looks like a dark basement or ship hold. Inside, an upside-down drinking fountain gushes water into a thousand-gallon tank that flows to a system of copper pipes. When the tank fills, a pump starts to recycle the water through the system. Pope.L has attached contact microphones to various parts of the tank so that one can better hear the dripping of the water inside the vat and the water pumps that drive the process.

The Whitney’s accompanying didactic quickly moves to explain the drinking fountain in terms of race and current events. Indeed, the artist does associate this weird machine to environmental justice, teasing out its resonance with the Flint, Michigan, crisis. Pope.L also bottled contaminated Flint water and sold it as art to raise money for the affected communities. But even after one knows the piece’s upsetting genesis, the environment is truly odd. You want to spend time there watching the tank fill, waiting for the water to drain, in another manifestation of Pope.L’s artistic bulimia (which is really what he meant in his manifesto).

Pope.L is in some ways a relic of the ’80s, still insisting on the street-level anti-aesthetics and shock values of Basquiat, graffiti art, David Wojnarowicz, and the whole messy explosion of creativity of the time. Nothing wrong with that—emerging from a cultural juggernaut like 1980s New York should be a badge of honor. And now that the craziness has long died down, it’s easier to see the serious underpinnings of Pope.L’s antics, whereas then people might have considered him just another wacky performance artist. The current political situation has made the wit and social commentary in all of his performances achingly topical—sad for the country, then as now, but a good time to make art.

member: Pope.L, 1978–2001, installation view. © 2019 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

Given his connection to that past, it’s also enjoyable to note the ways in which he has kept up with the times: his decision to go only by his last name, with its oddly placed period, feels like a rap star move. Or was Anderson .Paak inspired by Pope.L? Some of his more recent pieces have waxed relational, for example, 2004’s The Black Factory, a truck—like a food truck!—in which Pope.L traversed the country, asking local participants to donate objects that they associated with “blackness” (which he of course declined to define) to his traveling museum. The artifacts are hilarious. A box of “unwaxed butt floss” made by a company supposedly called “Heiny Brite”? A package of Magnum condoms?

It’s difficult to maintain such an irreverent sense of humor about blackness when just leaving the house can be lethal for people of color. But Pope.L—one of whose performances consisted of the simple instructions, “Be African American. Be very African American”—precisely calibrates spectacles that both satirize whiteness and scandalize blackness. He doesn’t highlight the suffering of black Americans as a way of stroking the humanitarian impulses of white philanthropists; he wants to show us that we’re all in the dirt, and sometimes that’s enjoyable, or at least bizarre.

member: Pope.L, 1978–2001, installation view. © 2019 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

In 1991, for example, he slathered himself in mayonnaise, a de facto whiteface, perhaps a response to Karen Finley’s chocolate-smearing, for a piece he deigned to call I Get Paid to Rub Mayo on My Body (sadly not in the MoMA retrospective). Another piece, Sweet Desire (1996), actually put him in a kind of tomb—buried in the ground up to his chest on a sweltering summer day, he watched a dish of vanilla ice cream melt for eight hours, unable to access it. As if the sight of a black American man, half buried, risking his life to consume unattainable white ice cream did not sufficiently signify both absurdity and class struggle, the piece also endangered his health. During one performance of Sweet Desire, the MoMA text explains, “he had to be unearthed and hospitalized.” For this work, Pope.L seems determined to keep laughing all the way to the grave.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.