James Hannaham

James Hannaham

Dan LeFranc’s withering new play is a comedy of cluelessness.

Mark Blum and Mare Winningham in Rancho Viejo. Image courtesy Playwrights Horizons. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Rancho Viejo, by Dan LeFranc, Playwrights Horizons, 416 W. Forty-Second Street, New York City, through December 23, 2016

• • •

Rancho Viejo, Dan LeFranc’s satire of California middlebrow values, bursts into life on the Playwrights Horizons stage, so full of deadpan bon mots it could be an elegy for Edward Albee. LeFranc’s witty, self-aware sendup of white suburban ennui and anomie also gets a boost from the enthusiasm of its magnificent cast and director Daniel Aukin, who accentuates the ensemble’s comic timing and gusto to create some of the most witheringly droll blankness and insincerity this side of Andy Warhol himself.

The territory of the play is so well-trodden that it seems almost miraculous that a typical Off-Broadway audience would care, let alone a black gay reviewer who has sat in theaters for decades giving side eye to white audiences as they receive “relatable” stories from all-white casts as if through sippy cups. The story concerns Pete and Mary, a couple in the imaginary affluent coastal town of the title, apparently married for quite a while, whose relationship could use some improvement in the communication department. Mary (played with great mousy determination by Mare Winningham) has recently had a falling out with a close friend and is depressed, convinced that she has no other friends; she’s desperate to connect with anyone, even her standoffish neighbors. Pete (Mark Blum, brilliantly working the cusp of childlike and demented) has so many big-picture inquiries that he overlooks the issues at his elbow—perhaps he’s deliberately avoiding them. “Are you happy?” he asks Mary at the start of the play, not meaning Are you happy in our marriage? but Are you happy in a philosophical sense? Gradually, Pete becomes obsessed with the breakup of the marriage of his friend Gary’s son Richard (whom we never see onstage), to the point of 1960s sitcom-level meddling. Pete makes semi-anonymous phone calls to Richard, tries to overhear people’s conversations about the divorce, and publicly wrings his hands over the fate of Richard’s unborn child. For two delightful hours and one iffy one, we’re invited to various house parties with these upscale boors, and often treated to the bittersweet aftermaths of the festivities.

LeFranc has an unusual combination of affection for and animosity toward these characters—you sense he knows them intimately and yet seems appalled by their cluelessness and avarice. Mary can be thoughtful and insightful, but she also wears bejeweled sweatshirts and fawns over a guy who paints whales at the local art fair. There are extended conversations about the spiciness of mustard, the tile in the kitchen, and whether or not Mary enjoys being called a mermaid. Mary gets flirtatious with Gary (Mark Zeisler, deliciously smarmy), a bearish blowhard who peppers his dude talk with badly pronounced Spanish and is writing a book he describes as “mostly politics but also some life stuff.” His friends Leon and Suzanne, a faintly boho interracial couple, and a fourth couple that includes a Guatemalan woman from a wealthy background all fail to inject anything resembling dissent into their social scene. Later in the play, two characters coldly insinuate that another character’s death represents an opportunity to buy his home. The ironies are vicious and often pass without comment: early, we see that character toting around an acid-green Ziploc bag full of crackers; later, we see his ashes in the same type of bag.

The foibles of this hideous community often play as high comedy, since the group’s stabs at profundity and sophistication seem misguided, tasteless, and futile—to say nothing of their apparent disconnection from politics or current events. (Some might have voted for Trump.) I wonder how the play would come off to someone in the habit of taking people’s words at face value, or unskilled at reading between the lines. Still, anyone who can perceive the gigantic distances between what these people say and what they actually mean can surf on wave after wave of unsettling subtext. In one of my favorite moments, at the end of a party scene, Gary declares, “I really like these guys!” with so much aggression that it’s almost frightening, like Jack Nicholson in The Shining.

Mare Winningham and Marti in Rancho Viejo. Image courtesy Playwrights Horizons. Photo: Joan Marcus.

The gorgeous interdependence of wonderful performances, zippy direction, wicked writing, and mise-en-scène of Rancho’s first two acts is rare and difficult to maintain, and it unfortunately does not survive the whole of the third act, though some terrific moments still come through. (Pete’s revelation, “We live in a time of great . . . great . . . television!” is my new favorite anticlimax.) LeFranc has crammed the first two acts with a virtual ballet of banality and snide dialogue, but act 3—like Mochi, Leon and Suzanne’s dog (played by Marti, a very talented golden retriever/chow mix)—goes missing through the porch door. Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise anyone that a play whose characters are so desperate to avoid connection should take so long to resolve, and that the resolutions that arrive after so much blatantly antisocial socializing prove flimsy. Pete and Mary sloppily attempt to patch things up, Richard gets back with his wife, Gary and his wife go on uncomfortably. Even—canine spoiler alert!—Mochi, who for most of act 3 seems to have been eaten by coyotes, emerges unharmed and unchanged. It’s almost as if LeFranc, or someone, became self-conscious about offending the Playwrights Horizons subscriber base after lampooning them so mercilessly. Almost everyone gets off too easily.

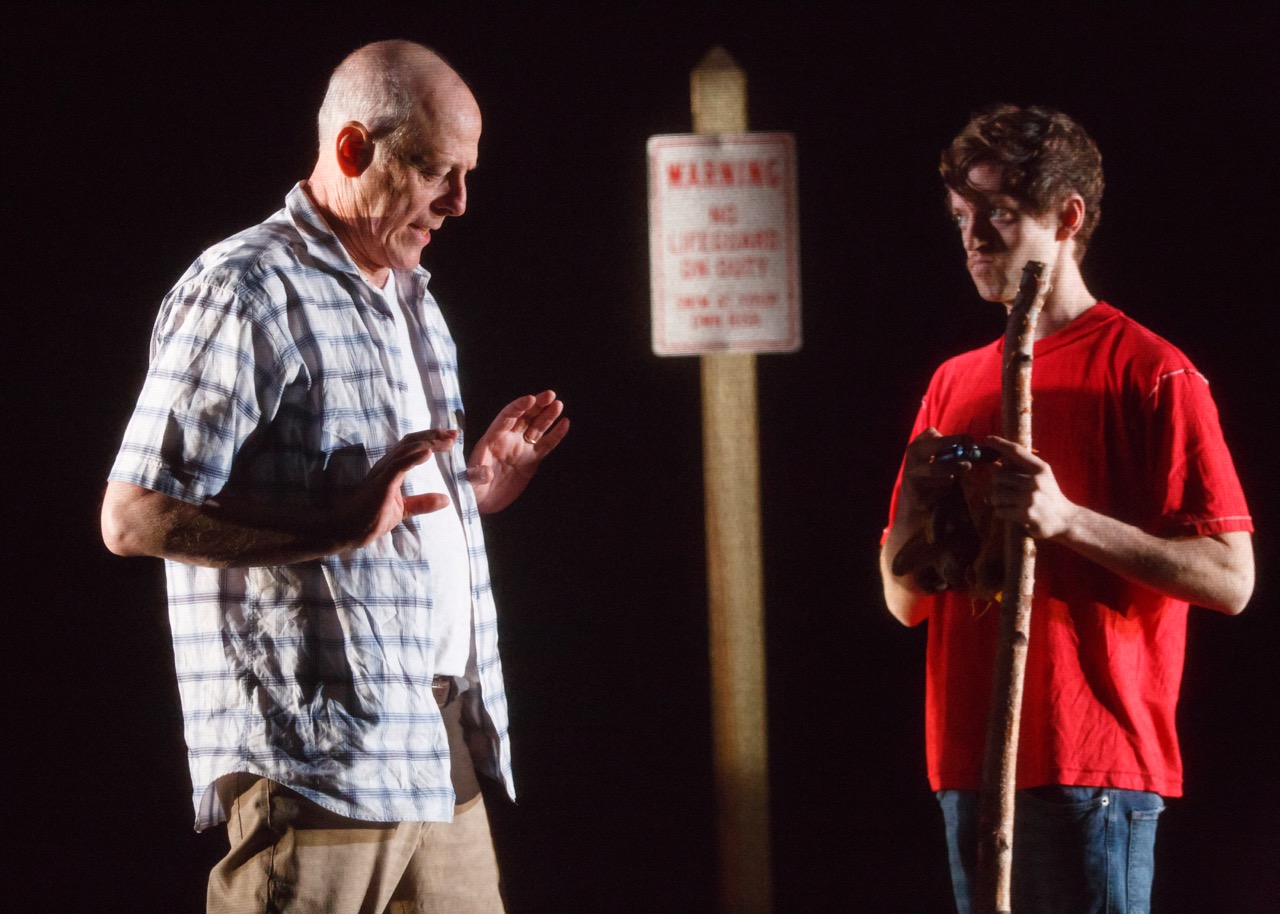

Mark Blum and Ethan Dubin in Rancho Viejo. Image courtesy Playwrights Horizons. Photo: Joan Marcus.

I found myself most moved, though, by the one character whose life does truly change over the course of the play—for the worse. Taters (“It’s long for Tate”), a marginalized, seemingly parentless, possibly queer neighbor kid (Ethan Dubin, charismatic yet creepy), makes Pete a captive audience for an oddly compelling modern dance recital on the beach. I can’t tell if his infatuation with Pete is erotic, father-obsessed, or a combination, but after his nearly naked, semi-embarrassing gyrations, Taters passionately craves Pete’s approval. But Pete rejects him flatly, cruelly: “You should really consider . . . maybe . . . never doing that again.” Taters, his spirit annihilated, gives up his artistic leanings and gets a boring job. Through Taters, we get to see how blithely the frivolous Rancho Viejo society ruins vulnerable lives. I found myself wishing the play had spent more of its third act excavating that truth and that it had left the audience similarly devastated.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.