James Hannaham

James Hannaham

Confronting mass media: a veteran Black artist receives his

first retrospective.

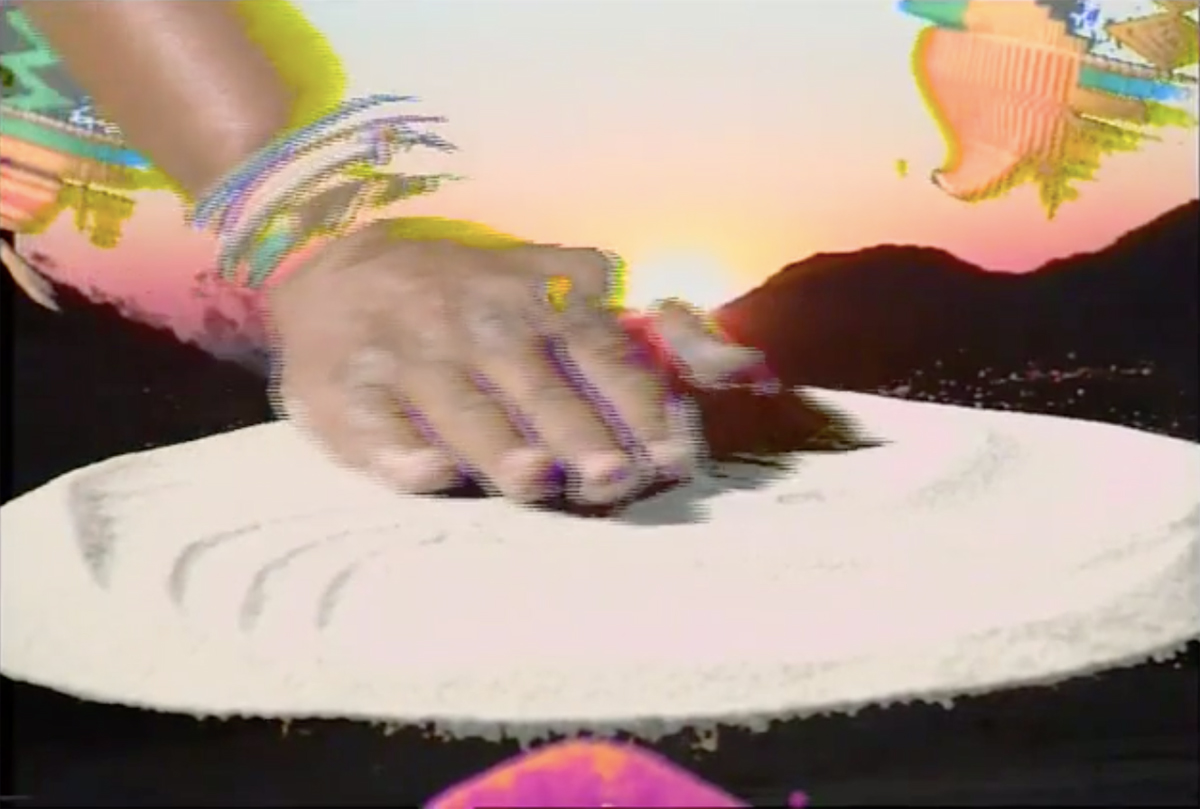

Ulysses Jenkins, The Nomadics, 1991 (part III of The Video Griots Trilogy). Color, sound; 12 minutes, 36 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation, curated by Erin Christovale and Meg Onli, Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 118 South Thirty-Sixth Street, Philadelphia, through December 30, 2021; travelling to Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, February 6 through

May 15, 2022

• • •

When you’re “young, gifted, and Black,” as Nina Simone famously sang, “there’s a world waiting for you.” But if you’re old, overlooked, and Black, like Los Angeles video artist Ulysses Jenkins, you might have to wait a while for the world to catch up. At the age of seventy-five, Jenkins is receiving his first retrospective, Without Your Interpretation, at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania (plus an exquisite monograph). This exhibit demonstrates nearly half a century of his quiet influence on and comradeship with artists—Black and otherwise—who have received a great deal more attention, including fellow ’70s Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) students David Hammons and Kerry James Marshall, both of them now MacArthur fellows. Even Jenkins’s professors at Otis have since become big names—Betye Saar, Chris Burden, and Charles White, painter of dignified Black portraiture, a similarly overlooked Black artist whose retrospective opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018, almost forty years after his death.

Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation, installation view. Courtesy Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. Photo: Constance Mensh.

The notoriety of Jenkins’s circle makes his omission from the limelight confusing, but he has been marginalized in almost as many ways as one can imagine. Primarily as a Black artist during the ’70s, but also as a video artist, a performance artist, a Los Angeles–based artist.

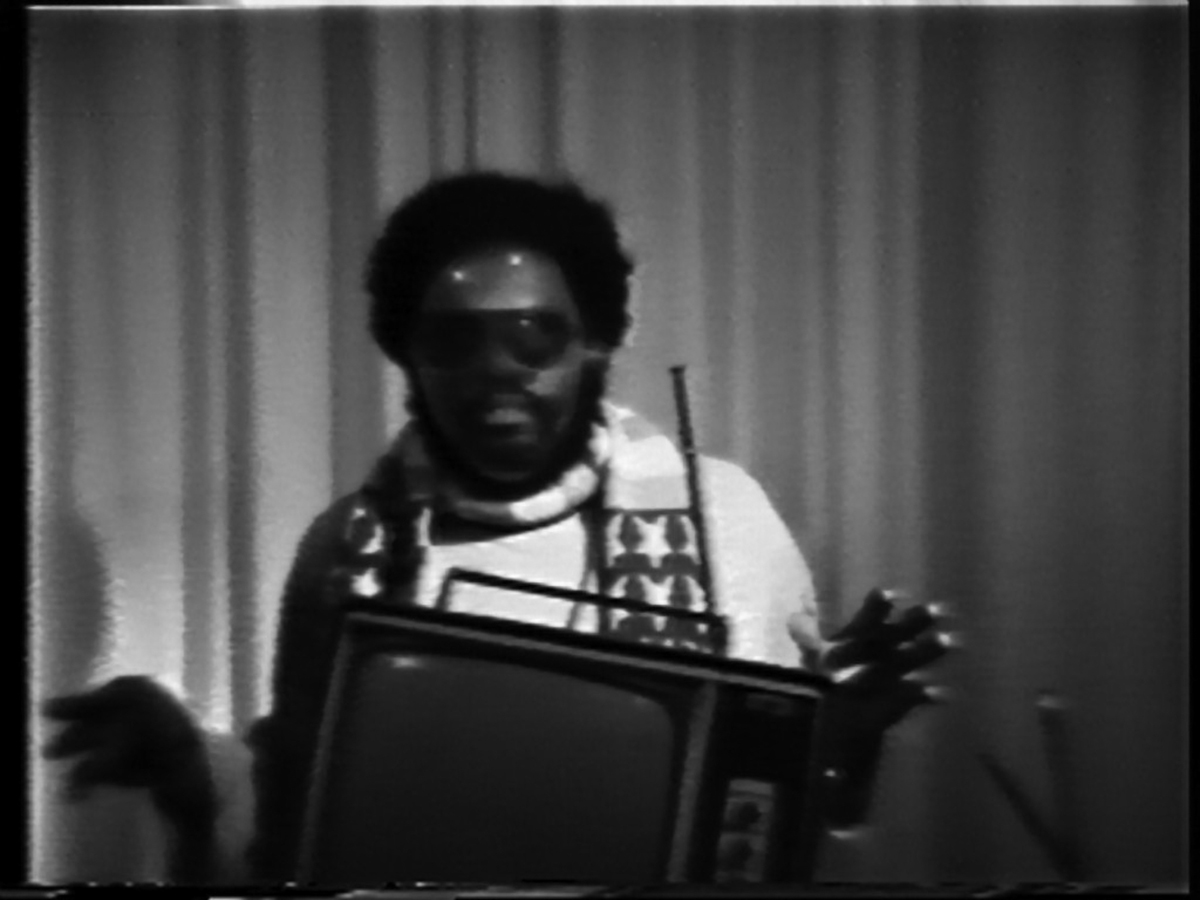

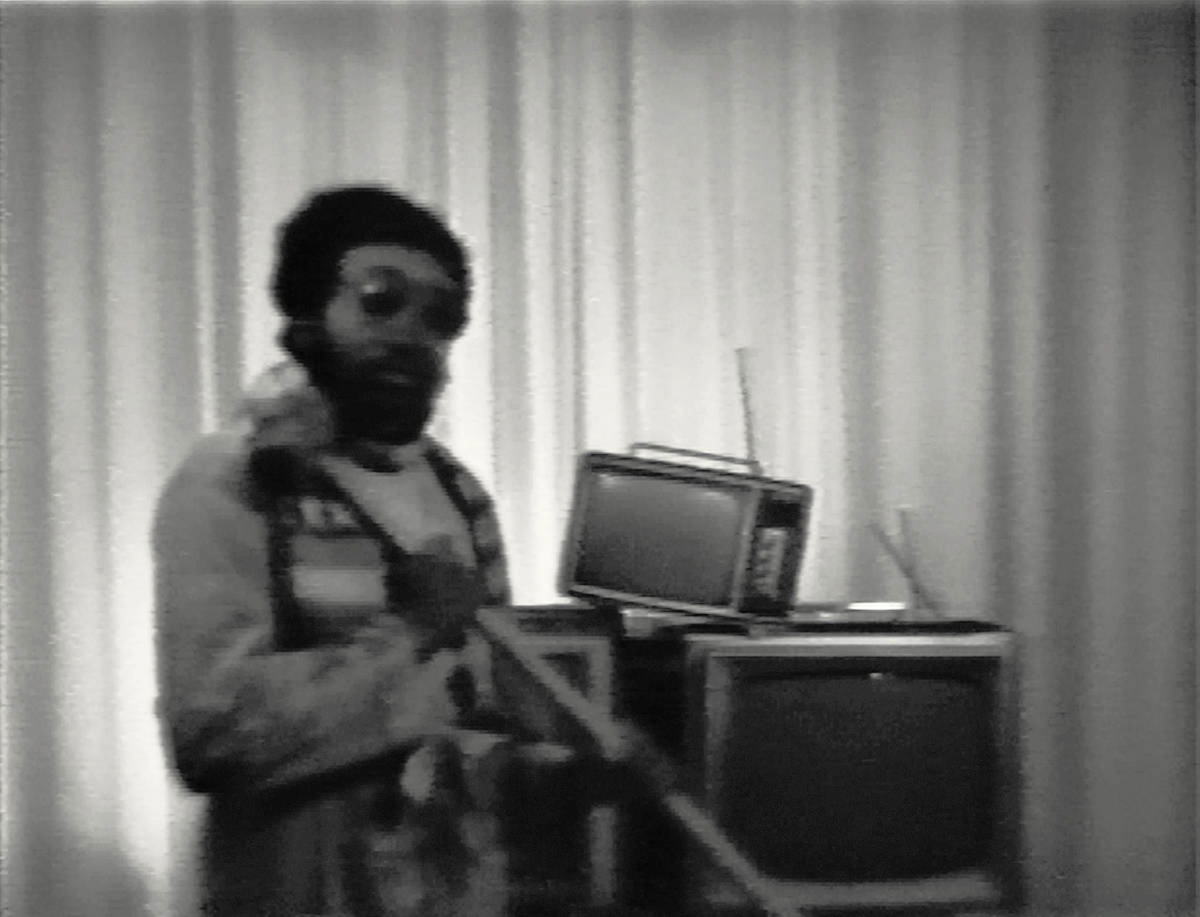

Ulysses Jenkins, Mass of Images, 1978. Black and white, sound; 4 minutes 16 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

There are lots of ways to explain the trajectory and recognition of a career, but they mostly lead nowhere verifiable. As a lifelong Angelino, Jenkins knew—and was skeptical of—the power of mass-media images, and before he was out of school made critiquing them a major aspect of his project. In 1978, while still a student at Otis, Jenkins created the video Mass of Images, described by the curators of Without Your Interpretation as “one of the first works in the genre by a Black artist.” This video juxtaposes racist caricatures of Black people from American cinema with footage of Jenkins dressed in vaguely revolutionary garb—dark sunglasses and an American-flag scarf. Brandishing a sledgehammer above a pyramid of TV sets, he impassionedly repeats a poem to the images themselves. “You’re just a mass of images / You’ve gotten to know / From years and years of TV shows . . . I don’t and I won’t relate / But I think for some it’s too late!” Yet toward the end of the video’s four minutes, he declares that he can’t smash the televisions. “They won’t let me,” he says, although he refrains from telling us exactly who “they” are—perhaps the powerful forces of oppression themselves.

Ulysses Jenkins, Mass of Images, 1978. Black and white, sound; 4 minutes 16 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

This failure to do damage to the mass of images, as Aria Dean suggests in her catalog essay, represents Jenkins’s desire to embody the condition of Blackness rather than to depict idealized Black power. “Jenkins is interested in questioning the very nature of blackness itself,” she writes, daring to look at Blackness at its most frustrating and powerless. The problem, says Dean, “is not that the image fails to correspond to reality, but that the image has partly crafted reality.” For Jenkins, smashing the TVs would not go far enough; the harmful effects of stereotyping are more than superficial, the power structures that uphold them too entrenched.

Not to destroy the offensive televisions, however, goes against two ’70s art commandments: the transgressive anti-aesthetics of, say, Burden’s Shoot (1971), and the Black Arts Movement directive to counteract racist images by reversing their power dynamic, as in Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). The critique of racial discrimination presented by Mass of Images is at heart a demonstration of why it endures. This stance, however, gives exactly nobody the quick fix they want or expect, definitely not in 1978, maybe not now.

Ulysses Jenkins, Inconsequential Doggereal, 1981. Color, sound; 15 minutes 20 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

Instead of conforming to white art-world transgression or Black Arts uplift, Jenkins chose not to water down his practice into anything easily digestible or blunt (let alone salable). He just amplified the difficulty, concocting Inconsequential Doggereal (1981), a fifteen-minute-and-twenty-seconds collage of brief videoclips, some grabbed from TV, some composed by the artist, including bits of network news, an unintelligible argument between a Black and a white man, shots of the artist’s naked ass, and early video animation. This image salad, born the same year as MTV, “scrutinizes the inconsequential terror that consequentially shadows and governs the everyday,” CUNY film professor Michael Boyce Gillespie points out in the monograph. For the title, Jenkins coined the portmanteau doggereal, which he returns to frequently to suggest the crudeness of quotidian experience.

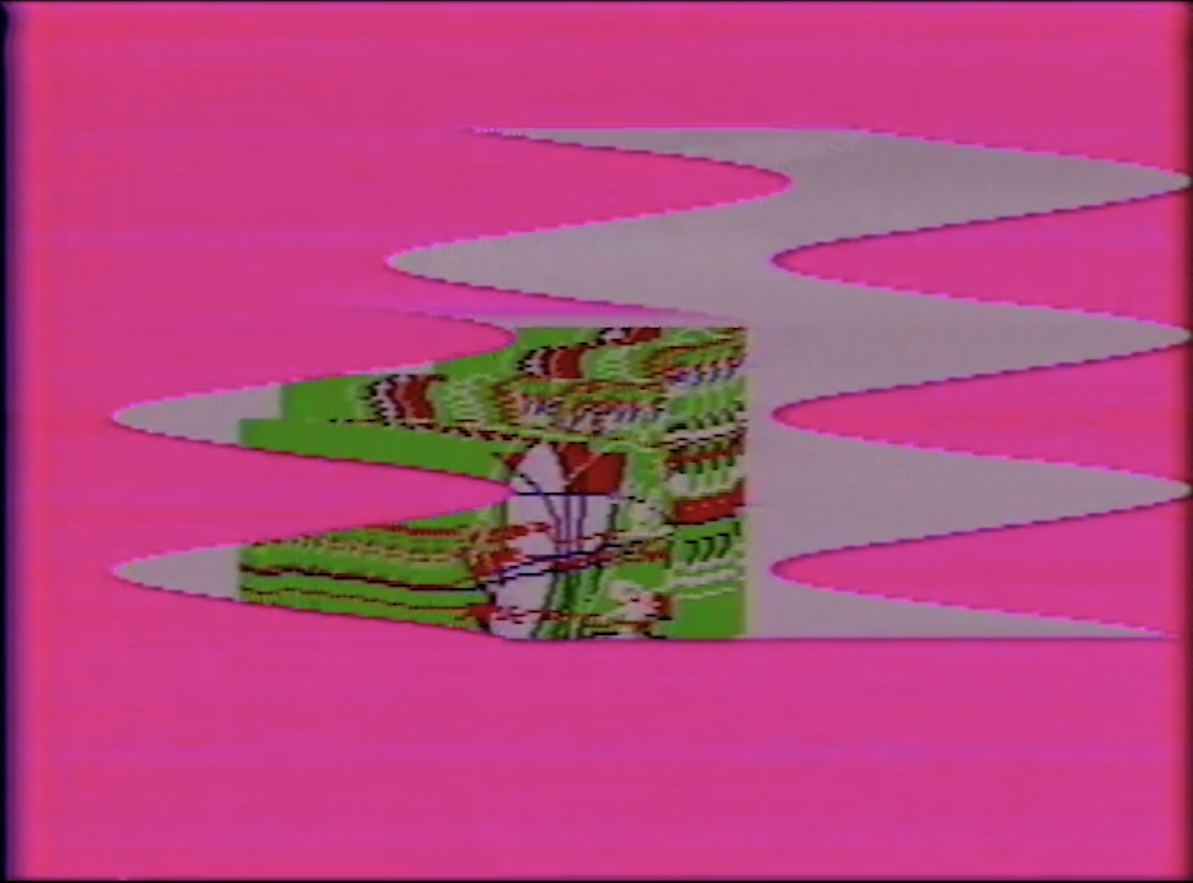

Ulysses Jenkins, Z-Grass, 1983. Color, sound; 3 minutes 3 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

In the ’80s, Jenkins created Othervisions Studio, an umbrella organization for collaborations with a diverse group of artists and musicians. He was shifting toward a utopian, multicultural vision, further away from a glorification of self or an easily definable body of work. The ICA retrospective devotes a large room to the output of Othervisions, including Z-Grass (1983), a series of acid green, blue, and fuchsia computer animations whose early technology now makes them look quaint. Intriguingly, the abstract swirls and scribbles of Z-Grass recall a mixture of American Indian and African textiles; one of the simplest pieces in the show, it communicates Jenkins’s zeal for cultural unity more clearly than many others. That may be because there are no bodies anywhere in the piece, and this frees Jenkins from the burden of representation, whereas in other works, figuration adds layers that don’t always come together as neatly.

Ulysses Jenkins, The Nomadics, 1991 (part III of The Video Griots Trilogy). Color, sound; 12 minutes, 36 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

Even at moments when Jenkins seems to adopt the visual language of Black liberation clichés, he has trickier motives. The Nomadics, for example, from 1991 (the culminating chapter of The Video Griots Trilogy), is a video montage of images of the type that could appear on greeting cards in Afrocentric bookstores, representing various cultures with beauty and dignity, fading in and out as a New Age soundtrack plays. Black hands caressing grain, stately mountain ranges at sunset, brown hands beating drums, Amharic script, and so on. But his nomadics are multicultural, not just African; he absorbs India, Indonesia, Polynesia, China, and Mesopotamia into an idealized Black and brown diaspora based not on the slave trade or a desire for Western modernization, but migration and trade on the other side of Africa—no chains depicted. As contrived and familiar as the images look, this is still a radical way of mythologizing the connections between these cultures.

Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation, installation view. Courtesy Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. Photo: Constance Mensh.

Many of the videos presented in the show are already accessible online, which is certainly an advantage for reviewers, but this fact makes it harder to insist that it’s absolutely necessary to experience the show in person, especially for anyone uncomfortable in public space during a pandemic. The ICA has done a fine job of organizing this trove of archival video, cleaning up the audio, contextualizing the entire oeuvre, making it look better than it does on your laptop, and in a few cases blowing it up to the size of a wall. But when you consider the situation further, watching all of the material would take quite a lot of time, and Jenkins’s camera is far from candid. Clearly, the kind of skimming everyone does in galleries will cause most people to overlook vital aspects of the work. This disadvantage has probably also affected Jenkins’s career negatively over the years. But take heart—when you go home wondering what you just saw, you can easily look again. Chances are you missed something.

James Hannaham’s most recent novel, Delicious Foods, won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. His next book, Pilot Impostor, a bevy of multigenre responses to work by Fernando Pessoa, comes out on November 30, and his third novel, Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta, is set for release in June 2022. He teaches in the Department of Writing at the Pratt Institute.