Zack Hatfield

Zack Hatfield

Country artist, conceptual artist, Texas artist: a celebratory biography of the rangy life and work of Terry Allen.

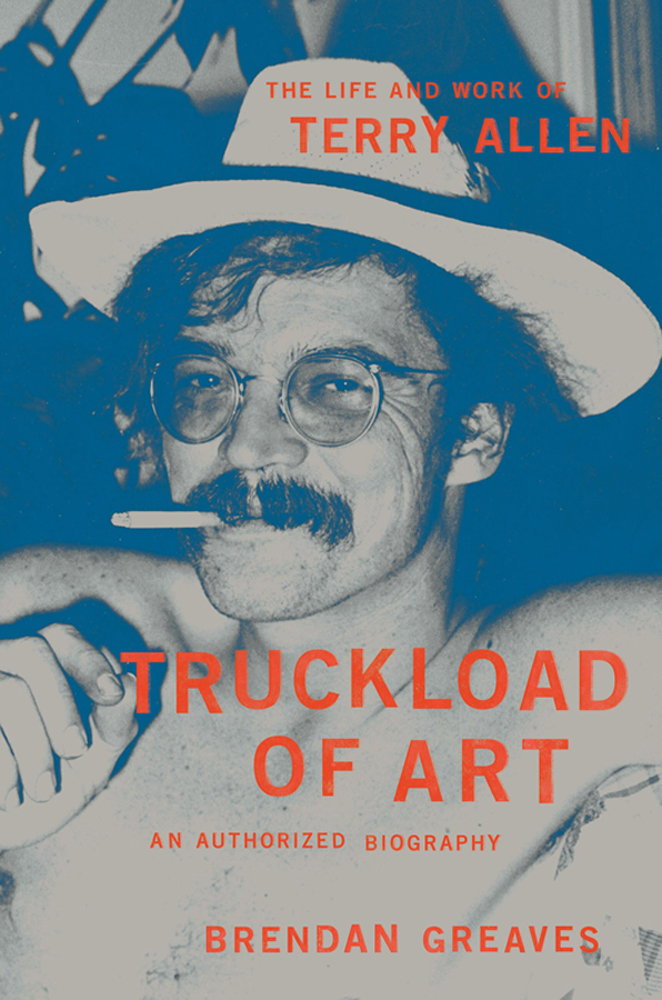

Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen, by Brendan Greaves, Hachette Books, 541 pages, $34

• • •

Once asked for his definition of art, Terry Allen said, “To get out of town.” Allen’s town is Lubbock, West Texas, a place so flat that, as he says, “on a clear day, if you look hard enough in any direction, you can see the back of your own head.” Straddling the subworlds of country music and conceptual art, his rangy oeuvre—songs, drawings, prints, sculptures, installations, theatrical productions, videos, radio plays, screenplays, prose, and poetry—forms a kind of psycho-mythic borderlands road map, all routes winding back to the Lone Star state of mind. Now eighty, the Texas artist—Allen, long based in Santa Fe, somehow makes that pigeonhole seem more expansive than just plain “artist”—is enjoying a late-career revival, in large part owing to Paradise of Bachelors’ 2016 reissuing of Juarez (1975) and Lubbock (on everything) (1979), the albums on which his reputation rests. Brendan Greaves, cofounder of the label, has followed up that project with an authorized biography, Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen, which celebrates the artist’s singular, hidden-in-plain-sight career and defends his place in both the art-historical canon and the modern American Songbook. Though, as Allen likes to quip: “People tell me it’s country music, and I ask, ‘Which country?’ ”

In Greaves, Allen has found a meticulous and empathetic Boswell. Across more than five hundred pages, he unravels a dense chronicle of the man’s Panhandle lineage and upbringing, education at the Disney-sponsored Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts), exhibition-making, business setbacks, studio sessions, Zelig-like encounters (with Marcel Duchamp, Nancy Reagan, the Manson girls), depressive episodes, struggles with addiction, and marital vicissitudes with his high-school sweetheart and chief collaborator, Jo Harvey Allen (their sixty-second anniversary is this July). Despite the book’s picaresque structure, Allen mostly embodies Flaubert’s famous advice to be regular and orderly in life so that you may be violent and original in your work. Truckload emerges not as a standard tale of the rise and fall (or fall and rise) of a tortured genius outsider/outlaw, but a patient study in artistic process and memory, the cultural intricacies of the twentieth-century West, and in people, how they scar and save you, like the lightning in Allen’s song “Cortez Sail”—“tearing the clouds, then closing the tear.”

Allen’s father, Sled, played pro baseball before becoming an influential promoter of wrestling and honky-tonk acts. His beloved and beautiful mother, Pauline, is invariably described as “haunted”: a lifelong flapper who played barrelhouse piano and terrorized her son with her drunken absences, especially after Sled’s death, in 1959, when Allen was sixteen years old. In ways good and bad, she evoked elsewhere. Lubbock evoked nowhere, a windswept void. In his telling, not only did the town claim only one museum (exhibiting farm equipment) but also one tree (farmers drove hundreds of miles to observe it). His formative encounters with visual art were his uncles’ ancient sailor tattoos. Music was less scarce. Sled brought to Lubbock giants like Hank Williams, B. B. King, Ray Charles, and a not-yet-Kinged Elvis, whom Allen met one day when the singer knocked on his door for directions to the venue. Their performances, like those of the mat-men his father showcased on Wednesday nights, gloried in a shared construct of macho authenticity that Allen would later inhabit and ironize in his own songs.

Juarez was Allen’s Graceland. He cut the breakthrough country-noir concept album after temporarily returning to Lubbock from LA, where he had made professional inroads but remained fundamentally misunderstood, his songs seen as separate from his visual art. Released by his own now-defunct Fate Records and circulated mainly in art galleries, Juarez conjures a double murder, the colonization of the Aztecs, and Jesus’s crucifixion, its pair of pairs, or (per Allen) “climates”—a honeymooning sailor and a Mexican sex worker, a marauding pachuco and a semi-corporeal bruja—forever shape-shifting, colliding into each other. Accompanied by his piano, his boot, and stock sound effects, Allen elocutes these corridos in a twangy snarl, as on “Border Palace,” when he sneers, “I can feel my skinny body / slip like a knife into her perfume,” or when he reports Cortés’s 1519 arrival to Mexico, “a Spanish Christ / alive on his lip.” Allen parlayed Juarez into JUAREZ, a living Gesamtkunstwerk through which he obsessively reinterpreted and remediated his elemental tragedy in the form of drawings, sculptures, screenplays, and mise-en-scènes.

To my mind, Juarez announces Allen not as a “master storyteller,” as Greaves claims, but a mesmeric image-maker whose visions of love are silvered by a mortal ferocity. Here begins a high-wire standoff between sincerity and satire that finds its fullest expression in Lubbock (on everything), a landmark of regionalist postmodernism that Greaves calls an “accidental capitulation to home, to rootedness, and to love.” Abounding with slice-of-life portraiture, boozy waltzes, and art-world ditties, Lubbock opens with Allen’s signature, “Amarillo Highway,” narrated by a blustery local: “I don’t wear no Stetson / but I’m willin’ to bet son / that I’m a big a Texan / as you are.” For Lubbock, Allen had in fact traded his Lone Star MO for that of a spirited collaborator, assembling his polymorphous Panhandle Mystery Band with a who’s who of Lubbockite talent including Lloyd Maines, Joe Ely, and Curtis McBride. His next projects grew increasingly circular, as with RING (1976–80) and DUGOUT (1999–2006), ouroboric multimedia cycles exhuming the trauma of parental death. “I believe that Allen’s art is not so much about remembering as it is remembering,” Greaves writes, “an untidy record of the iterative act itself.” As critic Dave Hickey, Allen’s foremost exegete and the dedicatee of “Amarillo Highway,” wrote: “Not only are there no happy endings, there are no endings” in his art.

Greaves is a fluid, companionable writer. His deft interplay of analysis and anecdote—he traces Allen’s influential friendships with Hickey, David Byrne, Guy Clark, Bruce Nauman, Marcia Tucker, Al Ruppersberg, Ed Ruscha, Little Feat, H. C. Westermann, and Townes Van Zandt, among others—compensates for a tone of uncritical admiration that occasionally slinks into PR speak, as when he blandly avers that the artist has spent a career “bridging and belying the widening divisions that define and distort American culture and politics, now more than ever.” About whether this exhaustive account will thoroughly demythologize his cult subject, stripping Allen’s ciphers and climates of their mysterious lore, the biographer seems unconcerned—and perhaps rightly so. Terry Allen’s eccentric trajectory may irradiate a “parallel history of American artistry,” but his endless country will always be a country of one.

Zack Hatfield is a writer and editor living in New York.