Will Heinrich

Will Heinrich

The Frick hosts Divine Encounter, the Dutch master’s moving look at the story of Abraham.

Divine Encounter: Rembrandt’s Abraham and the Angels, installation view. Image courtesy Frick Collection. Photo: Michael Bodycomb.

Divine Encounter: Rembrandt’s Abraham and the Angels, the Frick Collection, 1 East Seventieth Street, through August 20, 2017

• • •

Rembrandt worked at a time when the individual and internalized sense of self we call our own was still in the process of being formed. You can see his profound exploration of the psyche on a grand scale in a canvas like Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653), on permanent display at the Met. But it’s equally present in the small but incandescent show Divine Encounter, curated by Joanna Sheers Seidenstein at the Frick Collection in a pocket-size gallery next to the gift shop.

The single painting whose loan from an unidentified private collection provides the occasion for the exhibition, a six-by-eight-inch oil-on-panel called Abraham Entertaining the Angels (1646), treats one of the more famous episodes in the life of the Bible’s first patriarch. Seeing three strangers approach his tent, Abraham rushes out to offer them a meal, and they reciprocate his politesse by letting him know, in the voice of God, that he and his elderly wife can expect a son the following year. Abraham already has a son, Ishmael, whom he fathered at Sarah’s urging with her slave Hagar. But once Sarah has provided Abraham with a legitimate heir, she’ll demand that he drive Hagar and Ishmael away, and God will advise a troubled Abraham to obey his wife.

Later, in what may be the most efficiently heart-stopping fifteen words in Western literature, God will also command Abraham to take Isaac, his predicted son with Sarah, up to Mount Moriah as a burnt offering. Abraham’s unhesitating, if presumably anguished, obedience, and an angel’s last-minute intervention to save the boy and substitute a ram in his place, is the central Jewish religious myth. For European Christians of Rembrandt’s day, it was the Old Testament’s most significant prefiguration of their own central religious myth, the Crucifixion.

Rembrandt, Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1646. Oil on oak panel, 6 ⅜ × 8 ⅜ inches. Photo: Michael Bodycomb.

That first scene of encounter, as Rembrandt sets it, is brown and gauzy, a perfect setting for what Seidenstein, in her catalog essay, identifies as his use of light to describe a gradual revelation of divinity. One angel, with his back to the viewer and wings tightly folded, sits in shadow, while a second, perpendicular to the first, eats daintily, his face partially illuminated by the bright yellow light that bathes a third. This white-robed third angel extends a foot for his host, who looks old enough to be his grandfather, to wash.

This revelation of the messengers’ ambiguous divinity can certainly be read as an explicit unveiling of superhuman characteristics. But it works even better as an externalized metaphor representing Abraham’s own process of coming to understand who it is he’s entertaining. The show contains nine supporting drawings and etchings. In three etchings in particular, Rembrandt organizes his compositions and even the stories’ secondary characters—though they’re all still fully realized—primarily to express Abraham’s emotional experience of the scenes.

Rembrandt, Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael, 1637. Etching with touches of drypoint, only state, 4 ⅞ × 3 ¾ inches. Photo: Morgan Library & Museum.

In the highly detailed Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael (1637), which is even smaller than the painting, the prophet stands sadly with his feet splayed and his arms outstretched, dressed up as if for a holiday. Behind his left shoulder, a resigned Hagar weeps into a handkerchief. At his left hand, half his father’s height but armed and dressed like a man, Ishmael begins the long walk into the wilderness. Behind Abraham’s right shoulder, Sarah leans out the window with a faintly sour smile—no revenge can quite erase the old humiliation of her longtime barrenness—while Isaac, complacent but cowardly, hides indoors.

Rembrandt, Abraham and Isaac, 1645. Etching and burin, state i/ii, 6 ⅛ × 5 ⅛ inches. Photo: Morgan Library & Museum.

In Abraham and Isaac (1645), father and son face each other on Mount Moriah. Isaac has just asked his father where the animal for their sacrifice is, and Abraham, working up the nerve to cut Isaac’s throat, hunches forward, clutches his heart, and points to the sky, as if to say, “God will provide.” But there’s something odd about the way he points. Though he’s ostensibly talking to Isaac, Abraham holds his hand with the palm facing inward, as if he’s really reassuring himself. Isaac’s face is shadowed and his body surrounded by darkness, and he wouldn’t, in any case, understand the ironic tragedy of his father’s answer.

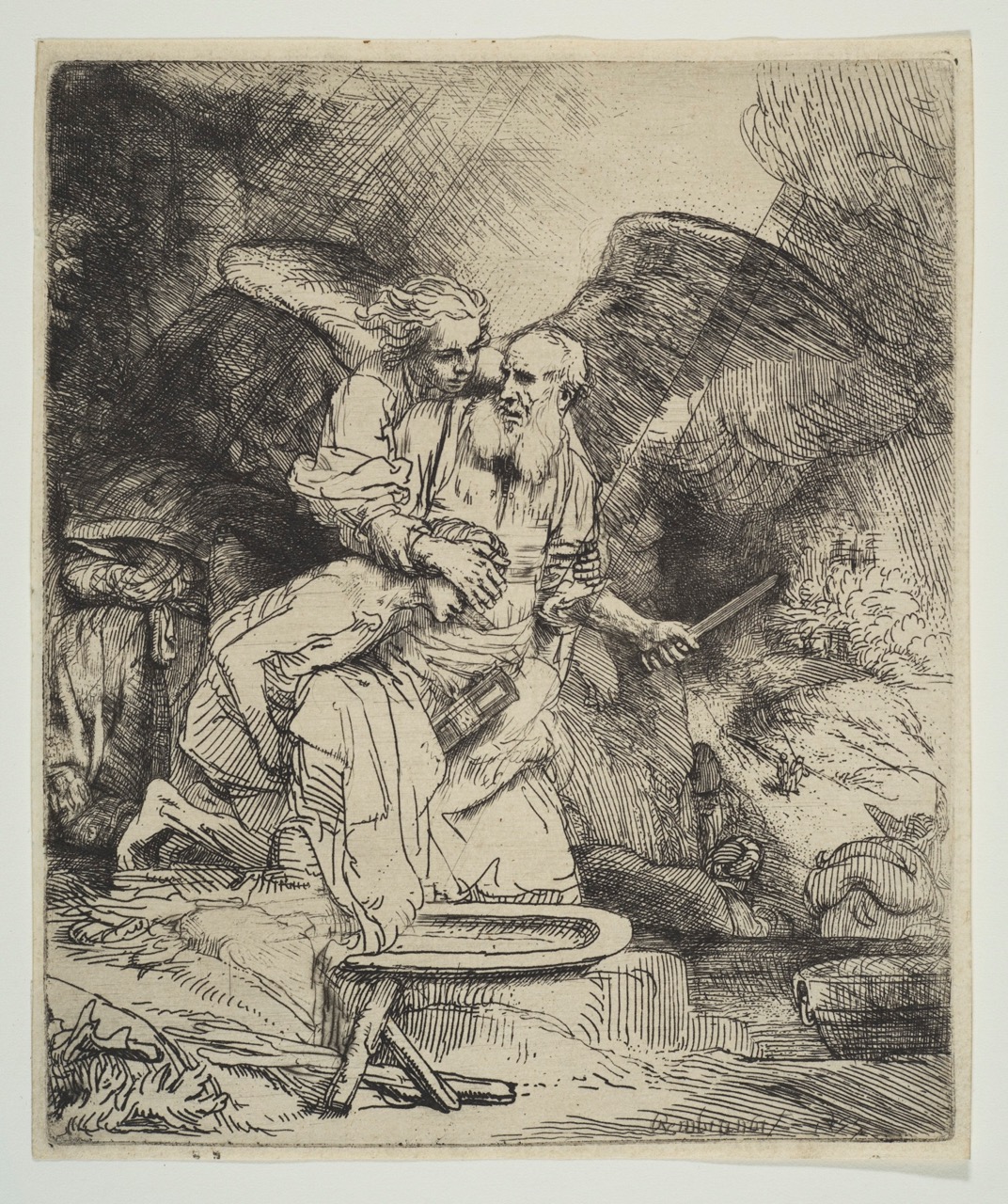

Rembrandt, Sacrifice of Isaac, 1655. Etching and drypoint, only state, 6 ⅛ × 5 ⅛ inches. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In Sacrifice of Isaac (1655), the son kneels tautly over his father’s lap, looking curious to learn the solution to a long-promised mystery, his eyes covered but chin cocked. An angel drops down with wings akimbo, arriving from heaven not a moment too soon, and embraces Abraham from behind. A beam of light slices from the picture’s upper-right corner across Abraham’s forearm, dividing the would-be victim from the fist that holds the knife. Speaking intently, the angel tries to catch the beleaguered old man’s attention, but again Abraham’s gaze drifts off to the side. He looks as if he’s awakening from a nightmare.

In every one of these tiny, momentous scenes, this colossal mythological figure, revered by half the world as the original prophet, is rendered as almost entirely passive. Expelling the woman with whom he fathered his first child, he is exhausted and downcast. Presenting his only remaining son with a well-intentioned evasion on the mountaintop, he looks absolutely crushed. And even as he does incontestably act in Sacrifice of Isaac, the action looks hardly intentional.

As a matter of drawing and engraving skill, that Rembrandt could put so much emotional specificity into faces the size of a dime is astonishing but not surprising. What struck me was his insight that the minimal, distantly narrated stories of Genesis can function so well as piercing dramatizations of interiority and the essential impotence of self-consciousness. In Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael, the “father of multitudes” stands at the center of a checkerboard of competing demands, with no way to go back in time and make everyone happy. His expression is one of confusion. In Abraham and Isaac, he looks more present, but what crushes him—what brought me, a new father, to tears in front of the etching the first time I went to look at it—is precisely his awareness that Isaac’s trust in him is misplaced. He has lost the innocence his son still has; he knows he’s subject to a capricious larger power. In Sacrifice of Isaac, his self-awareness reaches a peak of perceptive alienation—he sees himself move, but he can’t understand what he’s doing.

Will Heinrich was born in Manhattan and spent his early childhood in Japan. His novel The King’s Evil, published by Scribner in 2003, won a PEN/Robert Bingham Fellowship in 2004. He currently lives in Queens with his wife and daughter and writes about art for The New York Times.