Jeanine Herman

Jeanine Herman

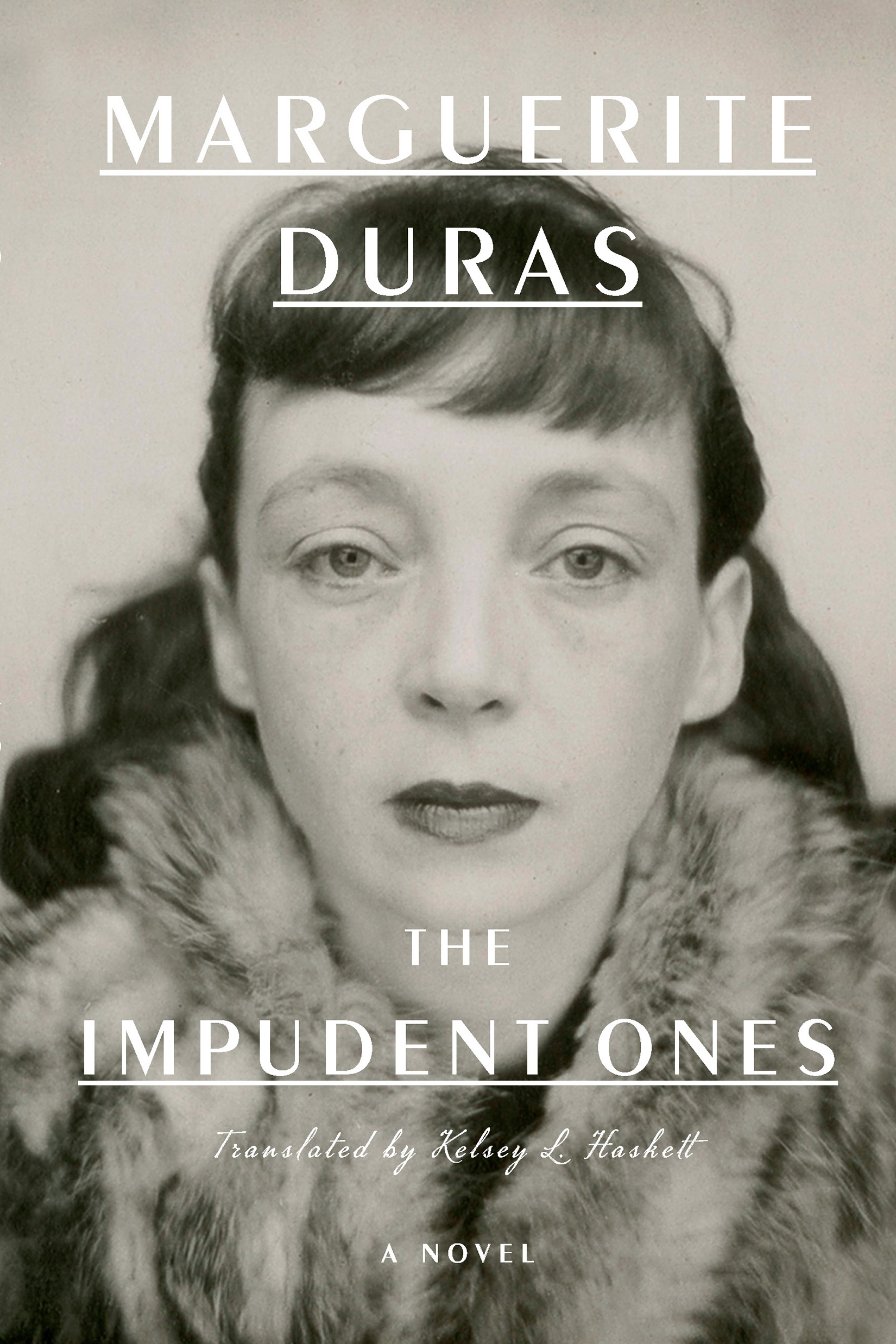

Marguerite Duras’s 1943 debut novel gets its first English translation.

The Impudent Ones, by Marguerite Duras, translated by Kelsey L. Haskett, the New Press, 252 pages, $25.99

• • •

The brilliant and prolific Marguerite Duras (known and revered for The Lover, rightly so, and her screenplay for Hiroshima mon amour, directed by Alain Resnais, and her pared-down, Editions de Minuit style) wrote a first novel called Les impudents, published in 1943. It is being issued here for the first time in English by the New Press, seventy-eight years later. It is an event, and a very beautiful novel, but not what one might expect or be used to.

She was twenty-six when she wrote it, and seventy when she wrote The Lover. By then she was a master. In this first novel, she is a young woman sorting things out.

And so this is not at all a new novel in the sense of the nouveau roman, with its spare and elegant, almost Zen aesthetic, but very much an old novel—an old-fashioned novel with fairly conventional language, which the blunt Marguerite Duras herself called very bad. It’s not bad, it’s just not what we think of when we think of Marguerite Duras.

An informal survey of friends turned up these favorites: The Sailor from Gibraltar; India Song; Destroy, She Said; The Malady of Death; and The Ravishing of Lol Stein (in the French, Le ravissement de Lol V. Stein, which stands for Lola Valerie and which makes a nice alliterative cell of Vs; it is a novel full of memory lapses and writing in the past conditional, the tense of regret, a useless tense).

The Impudent Ones is not the hardscrabble French Indochina Duras, but the landed gentry of the French provinces Duras. The family owns land and that makes them noble in a sense. The family is really fairly ordinary and bourgeois. Class distinctions are noted. A farmwoman looks ridiculous in her hat, “a bright-colored bonnet,” which made “this farm woman look like a lady of the night.” Some characters condescend to the peasantry.

The French Indochina Duras is minimalist, brutal, incisive; the landed-gentry Duras is maximalist to the max, particularly when it comes to descriptions of nature—lush and lavish: weather and foliage, rain and hawthorn bushes, linden trees, running through fields, the scent of the country, “the light perfume of honeysuckle,” and mist and fog and rivers and reeds.

It was a fine day in June, despite the heat. Because of the recent rains, the grass was thick and luscious, and the air gave off the fragrance of sap. Thrushes flew low over the fields and the velvety whir of their wings made a rustling noise. From the tops of the tall poplar trees of the Riotor, goldfinches were singing, infusing the azure sky with their voluptuous, triumphant notes. The cries of other birds rang out far and near, piercing or modulating, and one had to listen carefully to distinguish a single cry from so many. Surrounded by the woods of Uderan, the silence seemed to repose on these innumerable murmurs of birds. Sometimes, similar to the unfolding of a dying wave, puffs of warm air traversed the foliage of the trees.

She took her pen name from this region, as Jean Vallier notes in his afterword: there were “woods, vineyards, orchards, meadows, and a tobacco plantation . . . east of the historical hill-town of Duras . . . the town from which Marguerite later took her nom de plume.” (Her actual name was Marguerite Marie Germaine Donnadieu.)

These are the roots of all to come. Seeds are planted in this strange soil, of writing, of solitude. An appreciation of solitude. The cultivation of alone time.

Her themes seem to remain the same: longing, staring out the window, horizons, love, loss, not wanting to be observed, feeling judged, but also judging. The life of the mind gives her some power over her melancholia.

She is still sad—full-on melancholia here. She goes down to the river to put her hand in it, considers rolling into it, decides to just lie in the grass instead. She’s being rebuffed by her family for a romantic interlude, and she’s run away. It’s ridiculous, but she has to flee. That is her other theme: fleeing.

Fugue states, flight, forgetting.

“Time passed, and it felt good to let it go by without expecting anything from it.”

• • •

On page 1:

Maud opened the window . . .

. . . her face was pale and etched with boredom.

Soon thereafter she is listening to her brother cry, less interested in his distress than how she looks as she listens:

Maud listened attentively, her tall frame leaning against the window and her face alert. She was attractive in this pose and her beauty emanated from her face like untamed shadows. Her pale, overly wide forehead made her gray eyes look even darker.

She doesn’t care about her brother’s tears, because he’s a tyrant, their mother’s favorite, a cruel sibling, a spendthrift, and a cad. He pawns the family heirlooms, gambles. He is fleetingly solvent, frequently in need of cash.

As far as he’s concerned, “She’s sentimental; she wants to be noticed.”

Is she one of the “sad beautifuls” (a category I learned of in a poem)? She does seem to aestheticize her own sadness.

“Boredom reigned at Uderan—dense and oppressive.” Maud reigns over the vast region of her solitude. She has yet to go from calamity to calamity, she is not yet acid-etched in bitterness or ravaged by time.

Later Duras proved her resilience. Early Duras is almost nineteenth-century in her description of the countryside, the furniture, the ways in which we fall from grace. But there is a happy ending (of sorts). Before the economy of style came the excess, an excess born of romanticism.

This could be an incredible movie about family drama in the French provinces along the lines of Arnaud Desplechin’s La vie des morts. Or even a miniseries. Traces of Thérèse Desqueyroux by François Mauriac, with its discontent in southwest France. It’s got a marriage plot. There are suitors. There are rivalries, romantic and sibling, echoes of Jean Cocteau, and even Brideshead Revisited (marrying people off, social distinctions, etc.).

In this well-cadenced translation by Kelsey L. Haskett, we are given a remarkable first novel that documents “the days’ unchanging flow,” their constraints, conflicts, “chasms of light,” their ferocity and consolations.

Jeanine Herman is the translator of works by Julia Kristeva, Julien Gracq, Kettly Mars, Jean Genet, and Francis Ponge. She is a Chevalier in the French Order of Arts and Letters.