Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

Remembering the late singer’s suave, swagger, and sweetness.

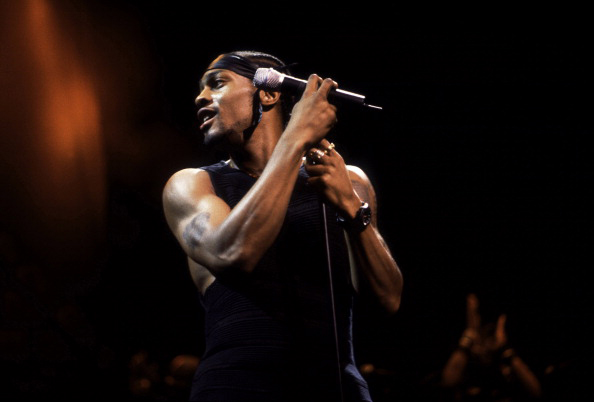

D’Angelo performs at the Aire Crown Theater in Chicago, April 2000. Courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Paul Natkin / WireImage.

1974–2025

• • •

Michael Eugene Archer, stage name D’Angelo, is dead at fifty-one. A collective jazz funeral has erupted for him in the etheric crypt we call the internet, one that seems more heartfelt and hesitant to cease its procession than many of the others in this digital tradition; there’s more rigor and heft to it, more devastation, more superstition and dread of where we’ll land when the celebration ends, as if in the absence of him and his culture-cleansing falsetto we are vulnerable to being haunted and possessed charlatans, mimic spirits lunging at us from the void. Earlier this year, singer Angie Stone, with whom D’Angelo had one son, Michael Archer Jr., died in a car collision.

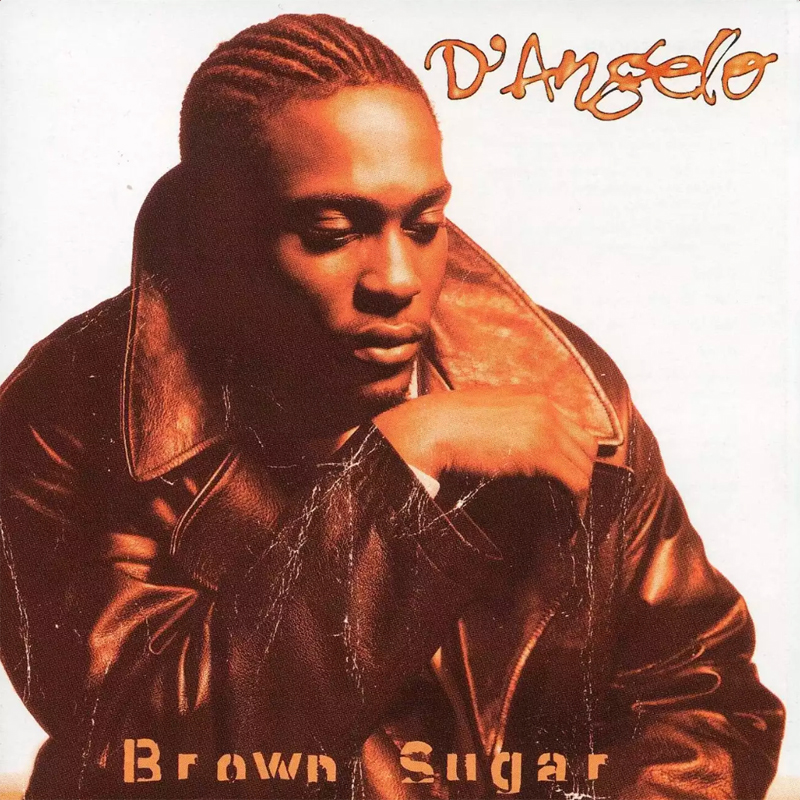

D’Angelo performs at KMEL All Star Jam at Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, California, August 1996. Courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Tim Mosenfelder / Getty Images.

Is the angel in D’Angelo’s stage name one of death or one of mercy? For a man raised by preachers in the Pentecostal church of his natal Richmond, Virginia, who described his role onstage as that of a minister delivering a drastic sermon to a restless, shiftless congregation, there’s a version of his unexpected departure from this plane, his young death, that the Bible eerily, almost threateningly, deems a tender mercy, a sacrifice he was primed to enact as in the black traditional dirge I wanna be ready / I wanna be ready / ready to put on my long white robe. D’Angelo was born ready, taught himself piano at three on an upright purchased for his older brother, and surprised their father with the accomplishment by playing Earth Wind and Fire’s “Boogie Wonderland” and Donna Summer’s “Hot Stuff.” When his father forbade him to play drums at home, D’Angelo kicked the piano’s trunk to inscribe the downbeat until he sounded like a one-man band playing eighty-eight chiaroscuro keys and the marionette he made of his own limbs.

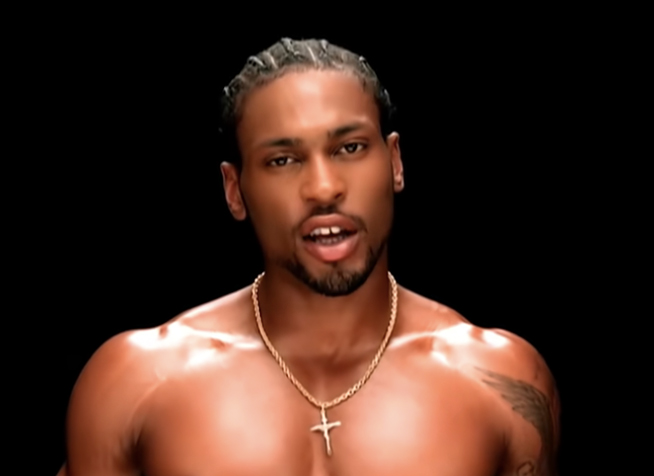

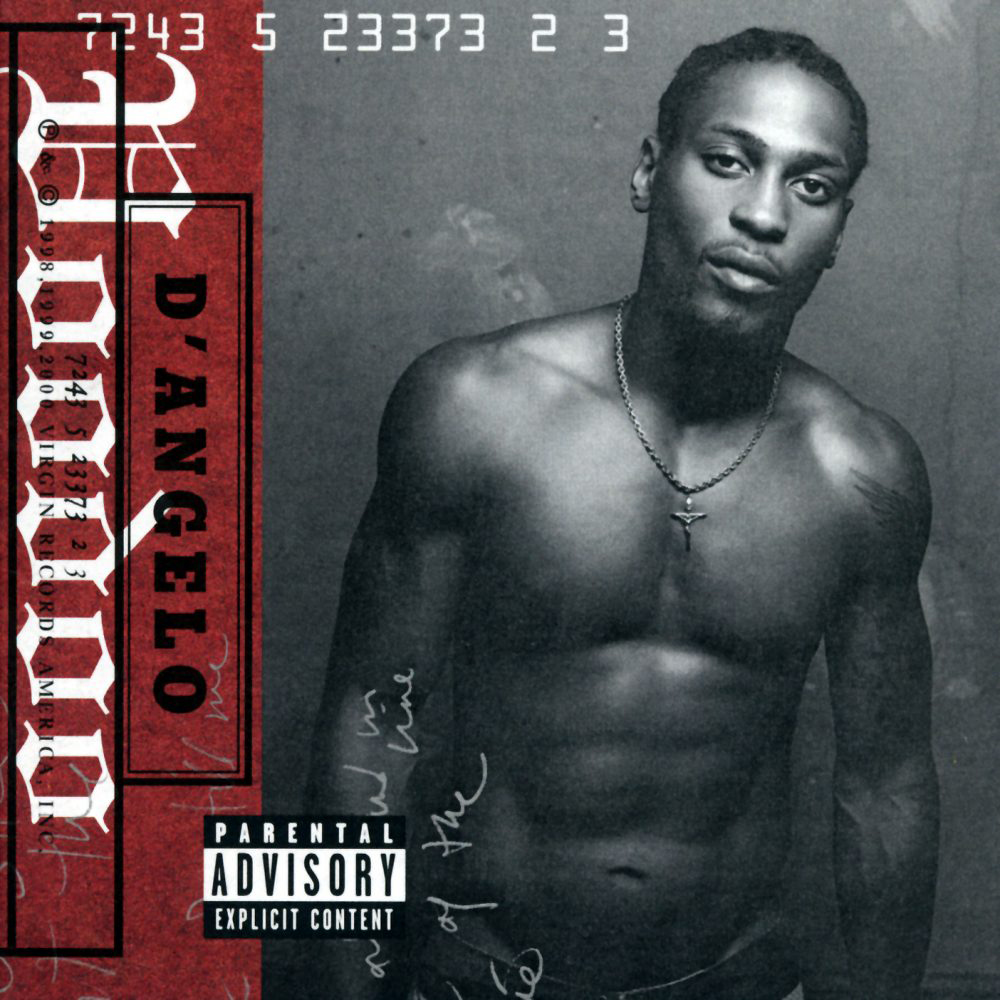

As a teen, he rapidly advanced from from winning amateur nights at the Apollo for three consecutive weeks to a deal with EMI and the release of his debut album Brown Sugar (1995)—a destiny he couldn’t have breached if he’d tried. He was born to shine and shed, practically a child star when he was signed at eighteen. And when he leaned into his glamour and physicality in perhaps the most erotic music video ever made, for the song “Untitled (How Does it Feel),” a talk-you-through-it homage to Prince that became omnivalent call-and-response between D’Angelo and Prince before Prince found God, wherein appropriation of his hero’s hyper-sexualized gestures became a shield for the world’s burgeoning obsession with him as brand, as the godfather of neo-soul—he became one of the decade’s dominant male sex symbols and black music’s Matrix-style redeemer, Neo himself. How did it feel? Now there were three: Michael, D’Angelo, and Neo, and his commercially released LPs were patterned in chronological order after each ascending archetype. On Brown Sugar, the lush sentimentality and symmetry of blissful inexperience flourishes, except for the revenge anthem “Shit, Damn, Motherfucker,” which seems to break from idyllic romance and bleed out into 2000’s Voodoo, where Pentecostal intensity assumes a Yoruba veneer to confess transgression that’s rendered the singer an exile pleading the blood and summonsing himself for reappraisal. By 2014, enchantment and the ghost-dance between good and evil are less compelling, and on Black Messiah, we meet the messianic D’Angelo; he wails and screams as readily as he croons, courting revolt as the culmination of sustained tenderness. Thus completes his hobbling, harrowing hero’s journey through the recording industry, biblical in proportion, abbreviated by the standards of those who fetishize accumulation.

Screenshot from music video for D’Angelo’s “Untitled (How Does It Feel).” Courtesy YouTube/Vevo.

But something feels unfinished, irreconcilable, lie-like, lilac wine with a whisky label, like he’s owed—money, apologies, another life. Looking back, there’s a casually distraught pressure in his gaze as he poses shirtless for the Voodoo cover, and the video that became so popular now seems a little like a hazing or humiliation ritual. He tells us he filmed it as testimony, a talk with God, thus playing the serpent in his own Eden, turning himself into a spectacle of hyper-sexualized despair. He is a celebrity clone of Michael Eugene Archer, mass producer of desire and profit, suppressing his prophetic nature to survive it. He makes himself into a decoy, with a perfect body and perfect soul, placates the obnoxious attention and then fakes his death again and again in subtle ceremonies, tattoos Psalm 23:4 on his impeccable shoulder like a brace—though I walk through the valley of shadow of death, I fear no evil, for thou art with me. And then he goes away walking, returns intermittently to tour or perform like someone staving off bounty hunters, debtors, that death wish, record labels.

Concerts rehearsed to be as serious as sermons, for which D’Angelo prepared intricate arrangements, vowing to never play songs exactly as they could be heard on his albums, turned into munera, the fight scenes between gladiators meant to offer spirits to the dead, as lascivious fans chanted take-it-off, take-it-off, gripping the fabric of his shirts so tightly the collars would strangle him. Eventually, he was shirtless more often than fully clothed, bearing his Adonis abdomen on red carpets and stages to discourage molestation, and one could easily disregard the substance in his music in order to experience him as a pinup. His retaliation, his counterspell, his Voodoo would be unveiled as a revelation that many missed for looking too hard. Don’t sing a gospel song, they’ll boo you—advice he received before his debut at amateur night. Between this and his skin of psalm, ambivalence would have to become his footstool, and in imitating Legba, the indecent trickster deity, the stool would wobble when mounted and he would fall for having trusted such a precarious foundation as the tension between faith and fame.

Dear Michael,

My friend and I are listening to your desert-island recording, Prince’s Under the Cherry Moon, and contemplating you in choked-up murmurs. It seems you possessed an uncanny capacity to soothe that which was marked for peril (black people), and it makes sense that this song, which romances a big getaway, dying in a lover’s arms as if on the cross, is your favorite. As Prince’s heir (and Sly’s and Sam Cooke’s, and Curtis Mayfield’s, and Marvin’s), your courage didn’t so much surpass his as emphasize it. You were all cursed with a similar ratio of beauty to truth. Black men ululating for love and desire with abandon, no matter whose sandman-scarecrow-type might disapprove and wrest you into the wings. And you and Prince both demanded unreasonable perfection from the body, suffered for that resonance, and were refused a future perfect in the end, taken from this purgatorial grift of a planet just when you might have been released from the tyranny of labels and contracts and left in the true messiah role to trouble their blunt saturnine standards. That’s the sparrow’s incontrovertible flight pattern, the virility of evil plans, the liberated minstrel turned minister gone rogue into quicksand. The more we discuss it amongst ourselves in hushed incredulous tones, the more I realize there’s a seemingly inconsequential and hidden vision within every artist at your level, usually unspoken or unspeakable, a testimony of hints. For you, it was the quartet tradition, your term. You longed to revive it, to harmonize acapella with three other men instead of in isolation—the sentimentalist, the shaman, the redentor notwithstanding, who would the fourth be? What leap were you preparing? We’re all behaving like bereft and delirious scavengers navigating an empire of sound that lost its final emperor, when what we really lost is a scapegoat we never deserved, ourselves, the magician’s last rebel-dove-crier, arbiter of endless carnal and sacred heartbreak and mend, defier of names and forms, exposer of counterfeits—we will fear no evil, for you were with us.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April 2022, and the extended UK edition was released April 2025.