Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

Revelatory songs of abandonment and abandon by the late Ethiopian composer and nun.

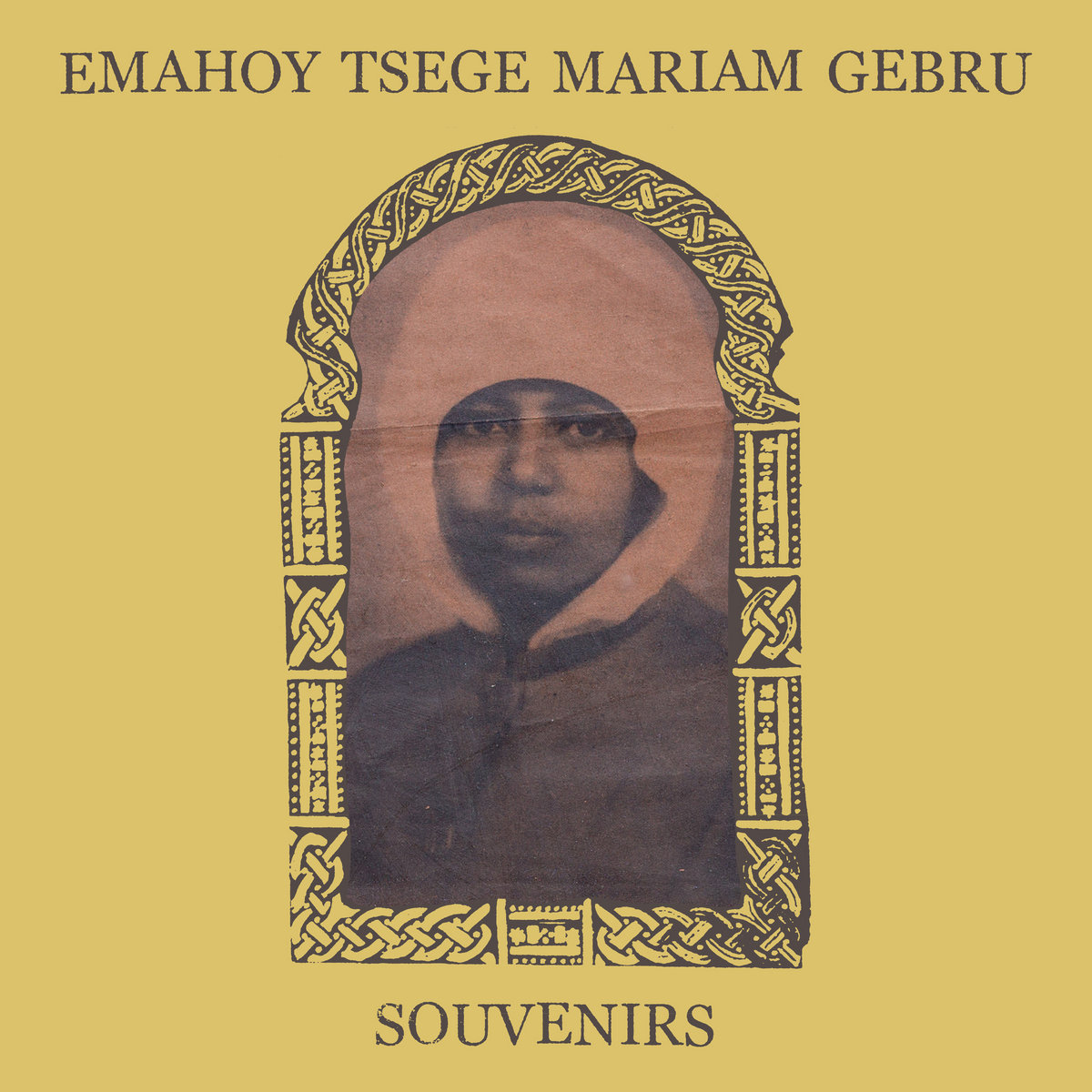

Souvenirs, by Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru, Mississippi Records

• • •

Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru is often flippantly monikered the “barefoot nun” or the “honky-tonk nun” in accounts of her life. This paradoxically reductive and sensationalizing shrink-wrapping of her path to asceticism is a naive defect of Western musicology. Within its codes, and those of Western popular music, there’s a hint of condescension to the sublime monasticism of any musician who refuses to behave as a traditional entertainer, no matter how drastic the conditions inciting that refusal. It’s pitched as bizarre and destabilizing. In Emahoy’s case, it was a practical act of transmutation. Born into Ethiopia’s high society in 1923, she was one of the first from her country to be sent to boarding school in Switzerland; she then went to study music in Cairo. Back in Addis Ababa, she rode horses in the hills and played her original compositions for Haile Selassie. She chose life as a nun after Italy’s 1936 invasion of Ethiopia and its subsequent violence interrupted her studies, preventing her from taking a position at London’s Royal Academy of Music. She was so disillusioned she stopped eating until she reached the brink of death. You can hear echoes of this waltz between abandonment and abandon in her playing; there’s a sense of gothic disenchantment that she rollicks in until it’s almost mirth, a private defiant smile or taunting song title, like “Why Feel Sorry,” uniting vengeance and resilience. When she absconded to places of worship, it’s as though the threat of death from external forces shocked her into catatonic fearlessness. Fearlessness in the face of death is so close to submission to it, and the strain of this proximity becomes her style on piano, sorrow so high it’s glamour or spellwork—a methodical pentatonic blues of confrontation and retreat marks popular recordings like “The Homeless Wanderer,” which is likely to bring you to the tears that occur when you’re mourning a terrible event you know lives in the music, or which the music is repenting; it’s as if what happened to her is happening to you. The intimacy that comes from being shocked into the present moment by compassion and suspense visits you through her, and entrances.

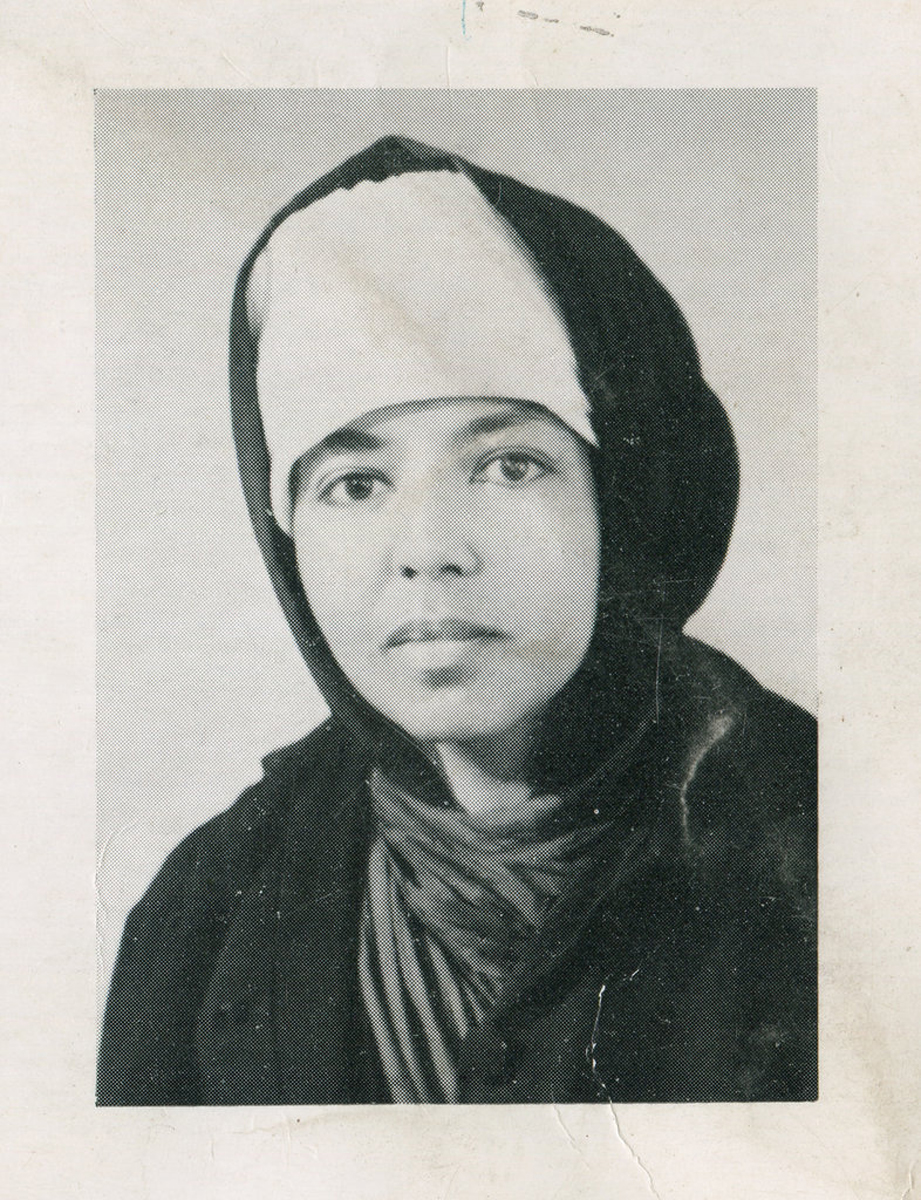

Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru. Courtesy Mississippi Records.

Emahoy was hospitalized during her hunger strike and given final communion, but woke up the next day having caught the holy spirit. She went to live at a convent in the hills outside Addis Ababa for ten years. She returned transformed, and resumed playing music, but only anonymously. She did not want to be an idol—she didn’t want to be seen at all, perhaps aware of how looking obstructs listening. A second invasion forced her final exile in 1985, this time to an Ethiopian Orthodox convent in Jerusalem, where she lived until she passed in March, 2023. In Jerusalem, she rarely had access to a piano and composed primarily on paper. She wrote poems in the middle of the night and set those to music transcribed in notebooks. She improvised her own quiet penitent protest liturgy, where protest was her commitment to spiritual life in the face of her homeland’s demolition. One tape of her devotional singing was recorded at her family’s home in Addis between 1977 and 1985, and sold as faulty CDs at the Jerusalem convent’s souvenir outlet to raise funds to keep things there afloat. The tape was corrupted and unrecoverable until recordings at its original speed were discovered in her room at the convent last year. Mississippi Records is releasing this first public account of her singing as Souvenirs. It arrives like a secret being divulged by a sage at the very moment it was intended, like premeditated justice, a frequency to counter our current limitations, a quiet scolding that negates some of the evildoing of hypocrites.

Emahoy’s room at Church of Kidane Mehret, Jerusalem. Photo: Cyrus Moussavi. Courtesy Mississippi Records.

History rhymes with itself for this release, as these songs were written during Ethiopia’s Red Terror, when tens of thousands were arrested or executed, among them members of Emahoy’s family. The recordings were clandestine, as it was a time rife with censorship, and hymnal verging on nihilistic, as the temperament might become during unnamed massacres. What should she have called her circumstance when she called on God? She beseeches in prayers and parables instead of direct exhortations. She sings to and of herself, as if singing to an inconsolable child, soothing a war zone into hush, inventing an inverse to violent colonialism. What would the inverse be, she seems to openly wonder in lyric after lyric. It would be the act of honoring private reverie, and inscribing the forbidden story of the assassinated and exiled onto seemingly unassuming melodies that double as a preemptive requiem for her own early life; her first life. She sings of her own rising from the dead, in haunting but tender jolts: why are we condemned / to be tangled in the sins of others / why are we condemned? the end of the first song, “Clouds Moving on the Sky,” laments, prophetically. It’s hard to imagine that she could have lived in Jerusalem and not understood how the condemned become arbiters of equally severe condemnation; her words are a balm for every involuntary accomplice to mass crimes.

Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru. Photo: Gali Tibbon. Courtesy Mississippi Records.

Personal catastrophe and social calamity combine to ensure that nothing after exile is secular or apolitical. Homesickness is militant and relentless. My heart has never stopped missing home, she confesses. And aren’t death and separation the same? Macabre, austere, but lush in the Billy-Strayhorn–“Lush Life” sense of knowing recompense is a new existence, in a new place, with fewer expectations of anything but the divine faith. We witness this commitment to spontaneous revelation in the many musicians who transition from secular to sacred compositions—from Emahoy to Alice Coltrane to Mary Lou Williams to Duke Ellington. In the handful of interviews available, Emahoy’s speaking voice is weary but delighted, hopeful but listless, and when she’s asked about her desires outside of piety, you can hear her unequivocal longing to share her music with the world. It’s not a longing to be famous, but the need to communicate, to be the griot who reminds the world of the Ethiopia she knew, a girl ago, a lifetime ago.

Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru. Courtesy Mississippi Records.

Emahoy is a wandering angelic spirit able to posthumously act on premonitions, who knew we needed her songs of sacred mischief and sullen enthusiasm exactly now. Where is the highway of thought, she investigates from her vantage of quantum recognition, and then she plays us the subtle, tremolo texture of waving goodbye to that highway in delay, from a distance—she drags her playing gently behind the voice, nears, pulls back, serenades absence and lag time like a wound whose scar she’s learned to cherish. This is an Ethiopian jazz funeral for her homeland, in a world where homeland is earned in bloodshed and no one really has one; she is both the griot who reminds us of what’s missing and the ancient, long-forgotten story the griot reveals. Emahoy is a revelation. These songs, as memories of what’s to come, are also poems on the page, and unlike her previous releases, they don’t mingle disorientation with sultry blues to cool their mournful muses. They are dedicated to her by her; songs of carrying the hearse into the sun to meet slain kin and strangers alike, they indulge alienation without reprieve. Her voice is gutting, gutted, plain, and at moments shrill with alarmed surrender. Let it go with love / Let it go with love she gasps on “Why Feel Sorry.” Emahoy actualizes in retreat, leaving in time to avoid the genocide on the horizon. The thrill of absconding, and the whimsy and jubilation and dejection of it, inspire in her final promise: resurrection, the last word on the album. Here are some redemption songs, she suggests, and I’ll come back for them, as them. After the poems, comes the music, she adds, piecing her birthright back together in psalms.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April, 2022, and her exhibition Black Backstage will be showing at The Kitchen in New York this spring.