Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

The musicality of both jazz and blues is at the forefront of a volume spanning forty years of poetry by the powerfully intractable Dionne Brand.

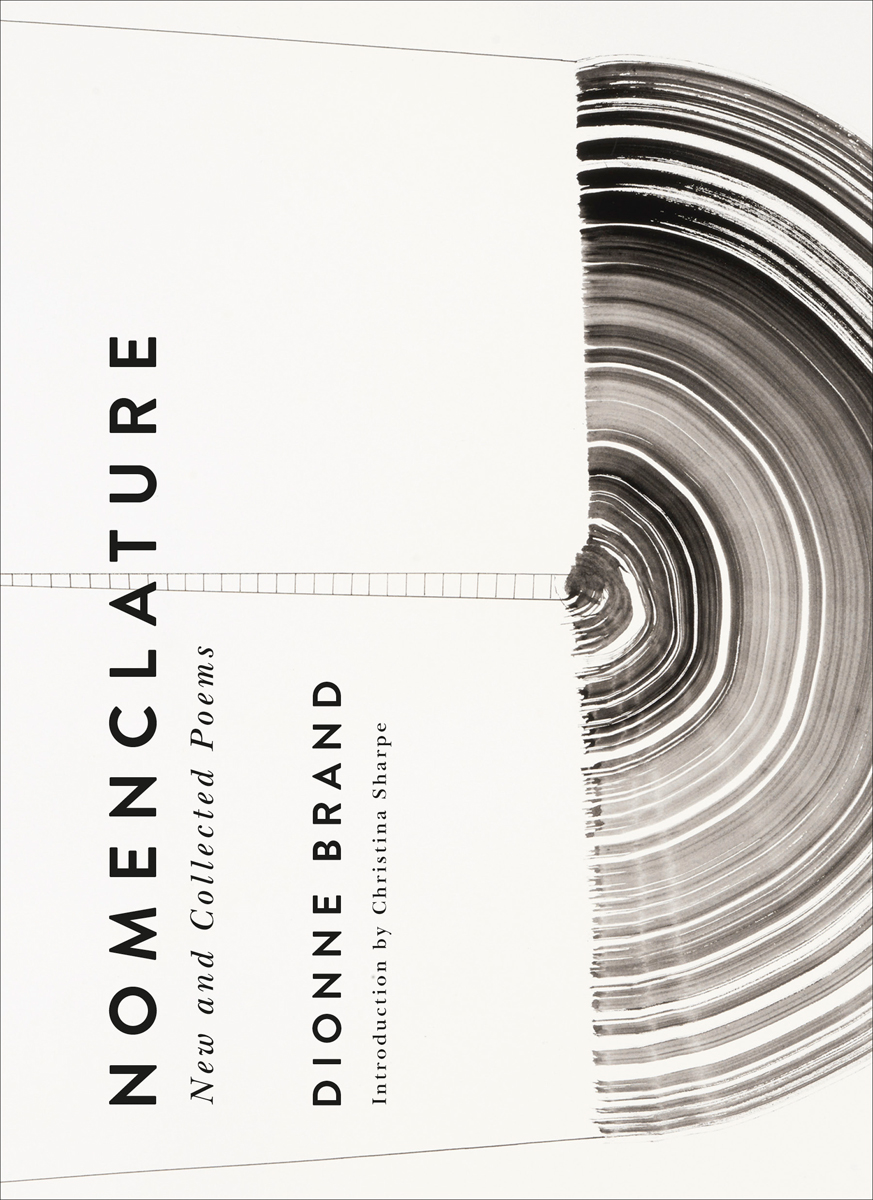

Nomenclature: New and Collected Poems, by Dionne Brand, Duke University Press, 619 pages, $29.95

• • •

The body bleeds only water and fear

when you survive the death of your politics

We all love the capricious immediacy of jazz music too much to be so dejected by the drastic changes the present imposes, I think to myself, while enthralled with Dionne Brand’s gleaming inventory of retreat. We all love jazz music, but the blues is our favorite color. Brand’s Nomenclature: New and Collected Poems is driven by sedate yet sparkling agonies that invent and occupy the limbo between blues spaciousness and frenzied free improvisation. The book combines a new, long poem, “Nomenclature for the Time Being,” with eight volumes of Brand’s work spanning from 1982 to 2010. Brand, born and raised in Trinidad but residing in Canada, composes from the muted hysteria of almost-exile. The duration of this collection allows us to watch her decorum unfold and rescind on the page, contained by an unwavering tidiness of form and precision of thought. This work is stubborn. It won’t relinquish its hopelessness or its insistence on redemption. They shoved microphones into our bawling mouths / and grief looked like archeaology.

Brand’s personal idiom is expansiveness cornered by rage but released from its cloister by the malaise of a perpetual reverie trapped between territories and land masses; it’s an idiom always digging itself back up from the wreckage. The poems shape into an archipelago and rarely stray toward the margins; formally they are tight ordinary machines, private enclosures, even while their thinking arrows into an unnameable beyond. She establishes fantasies that seem to wish for their own undoing, so that the dominant fantasy can remain revolution, which no daydream can undermine, which comes up again and again like a romantic interest that escaped or was snatched away by circumstance. The newest work has an heirloom quality. Its speaker is a woman who has inherited the apocalypse and does not want to squander it. She shines and buffs its jewels of lamentation with measured free verse akin to free jazz rising up out of an undulating nightmare blues, riding scraped palms and elbows tensed for psalm. Living / glistened on me, she promises, amid all the dead-end surroundings of plague. The musicality here risks its very life to be present and translate the now beyond the specter of a past that feels diminished by now’s banal urgency. Our noise was extravagant. Our need was / extravagant. The stakes are life itself, catapulted into the calm beneath the urgency of one run-on catastrophic moment.

This is the region called surmounting, she announces, then she surmounts herself, and her ego, with a signature and appalling accuracy that tumbles over itself page after page, stanza upon stanza, calamity after calamity, with no titles but the one overarching call for a new manner of naming our surroundings. The balance of the world, resuscitated here for the sake of interrogation, is so tenuous that any attempt to pander to comfort is blocked or flinches with self-doubt and severe modesty: do not distort the violence with any water / any love, any laughter, any ink / do not. Brooding is the more reliable accompanist in unfamiliar territory, brooding without pathos, brooding that uses itself, its whole body, to eliminate pathos.

Survival makes the speaker bashful, because to survive she had to survive her politics and accept the therapeutic insistence of poetics, which displaces ideology with beauty, a tendency that many poets fight until surrender becomes more interesting than war with the self. What is it that I loved / What is it that I said I loved, she wonders. If we cannot achieve complete liberation, this searching amnesia intervenes to appease us with a listless poetic liberation to soften the painful process of coming into a new set of desires. The world at present is reshaping desire to fit the drab contours of scorn, and the new work in Nomenclature joins that worldwide ensemble of tender fatalists. There’s a tone of preemptive disdain for triumph here that makes triumph inevitable, it’s slick that way.

We transition from 2022 to 1982, from the insistent now to Brand’s first collection, Primitive Offense. We begin traveling backward in time, and then back forward again, as each of her volumes here shows up like the last pillar of a monument about to be demolished. She has an uncanny amount of patience on the page, and encountering each book in succession like this feels like watching an archaeologist who knows exactly where the bones are, yet digs furiously, measuredly, in the wrong sites, to throw off the hunting dogs. At the same time she is lured into conversations and call-and-response exchanges with ghosts. To Amiri Baraka’s line from his poem “An Agony. As Now.,” I am inside someone / who hates me, Brand responds from her “I Am Not That Strong Woman” with I want nothing inside of me / that hates me. There’s a tentative hostility uniting each era of Brand’s writing and related affinities, a feeling of wanting to love and forgive a world and nations and men and women who have done nothing but betray and pillage. The forgiveness comes as renunciation and focus, dangerously direct focus, on the chasm between revolutionary roads and human ones. Blues ones and metropolitan ones. They all lead to the same inevitabilities she finds, the same digging and rebuilding. This civilisation will be dug up to burn all its manifestos, she promises. Grandiose claims of empowerment and change become futile to a speaker who comes to realize that her interior life is what she hopes to upend by saving the world. She achieves that rare tonal drift and drag between blues ruminations and jazz relentlessness, that feeling Billie Holiday accesses when she moves from “I Cover The Waterfront” to “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” or from adagio to allegro, as if one could never preclude the other. Cheerfulness is sullen in this Afro-Caribbean diasporic universe exiled at times to Canadian winters.

The snow-blue laser of the cop’s eyes fixes us / in this unbearable archaeology, she seethes, and later, in the poem “Blues Spiritual for Mammy Prater,” her meticulous account, her eyes . . . my turning the leaves of a book / noticing, her eyes. One cycle of poems divines the next, one sharp gendarme glance brings an ancestor back to life to peer in as witness and accuser for the next set of lyrics. The relay between the poet’s selves here is breathtaking. The phrase No Language is Neutral arrives at the bullseye of the collection—its most insatiable warning. It exhorts us to undermine Eurocentric casualness and neutrality without entertaining, without performing, that takedown for its purveyors. No minstrel here, but all of the bones of showing, as she states in Ossuaries, this genealogy she’s made by hand, / this good silk lace. How does a black poet deliver her perspective ceremoniously, as stark ritual, without pandering to the expectation that she dress these deliveries up in myths and larger-than-life antics so that readers do not feel implicated by direct address? Brand shows us how by doing just that and whether or not the revolution she imagined comes, this is a revolutionary act, to not act but to be so precisely that each small degree of change rivets and ripples as a self-contained justice that needs no codifying in outside laws. Some sang for no reason at all, she reminds us, while she and her readers are lucky enough to know that pure music does not answer to contingencies and disclaimers or wait for the canonizing of a liberation that has already been achieved by the spirit.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April.