Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

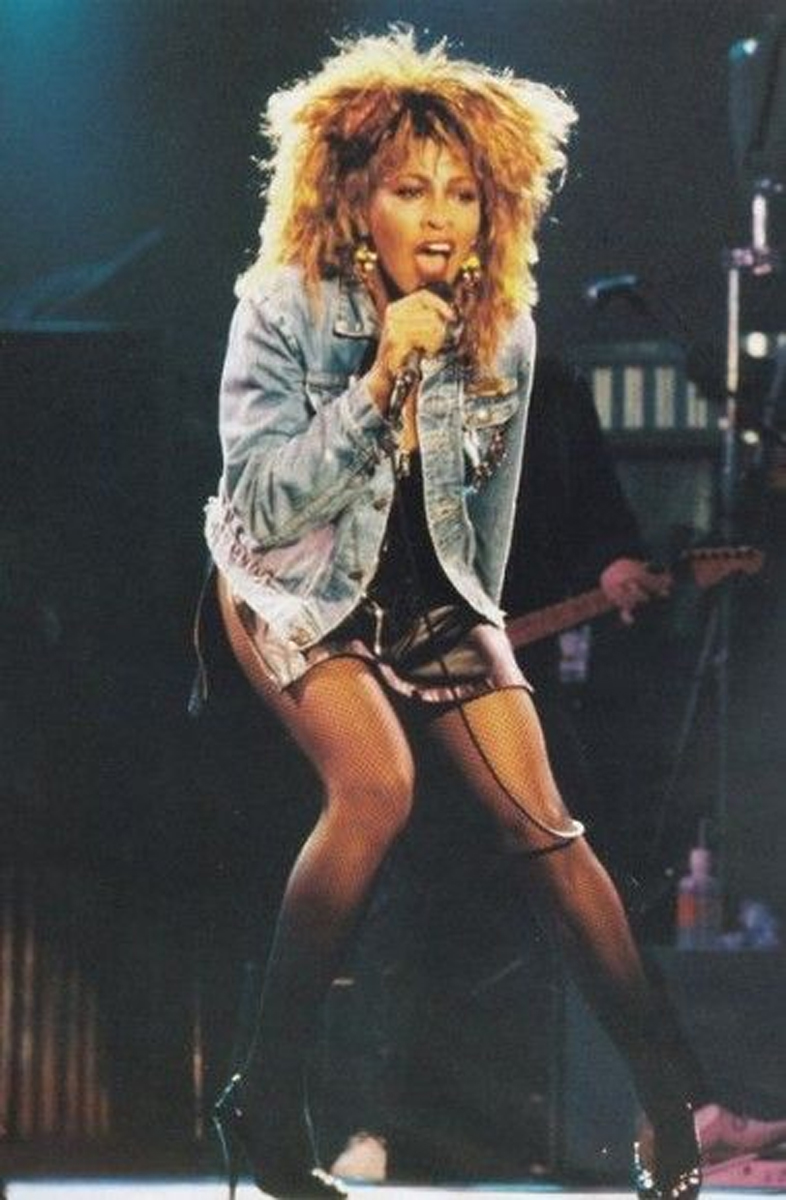

A tribute to all that we owe to the late, great queen of rock and roll.

Tina Turner and Ikettes perform for Bolic Sound KMET Broadcast, May 1973. Courtesy Warner Bros. Discovery.

1939–2023

• • •

What I mostly remember is flashing lights

—Tina Turner

I imagine that in the blurring of thrill and terror, on that night in July of 1976 when Tina Turner finally escaped the clutches of her rabidly violent producer husband, Ike, that the lights Tina described seeing on the freeway she crossed to get to the nearest hotel shared the caustic hue of cotton flowers. I imagine there were hallucinations and that a portal between eras opened for her. We did cotton, she said of her childhood in Nutbush, Tennessee. She came from a family of sharecroppers. It’s refreshing to hear her choose the did instead of picked here. It’s akin to a poet deliberately saying she did a poem to imply that the poem was alive and not static. And in Tina’s case, it corners the worn-out pathos of the phrase “picking cotton” into its habit tense and seems to counter-ask what do you think we did in those fields, in those days? The phrase “picking cotton” is so sloganized and tokenized no one listens when you say it, it’s like muttering the lyrics to a sad popular song that everyone smiles about. Tina defied this trope, and her uncanny ability to be explicit without being confrontational made her almost too perfect to survive the heaviness of her own virtues and talents, too maverick for some. She was the perfect performer, the perfect loyal wife, the perfect survivor, the perfect singer, the perfect understated-yet-undeniable beauty, perfectly seductive, perfectly heroic, perfectly resented—the perfect sacrifice. When she was generous or naive enough to give the world her memoir, I, Tina, in 1986, two years after her album Private Dancer had won her Grammys and worldwide acclaim as a solo artist, she was the perfect source of revelation about an afore undercover domestic ritual: ruthless uninhibited beatings that went unreported and unnamed in many households, and especially those of some entertainers.

Tina Turner. Courtesy the official Facebook page for Tina Turner.

Glamour had become a veil for a reformatting of abjection. Now, in the place of poverty, we did violence, we were so expensive we were dangerous, now we did cocaine, in Ike’s case, which intensified his temper, his paranoia, and his outbursts of rage. He would beat her, then rape her, ritual torture. He’d make her rehearse incessantly, like a circus act, with blackened eyes and swollen lips, yet her voice never slackening, only growing deeper, vaster, and more incantatory. He was possessive and a pathological womanizer. And after her escape and comeback (he took everything in their divorce but her name, which he had changed himself without consulting her), all journalists wanted to ask about was him, their marriage, and how it had trained and tried her. She wrote the book, she said, so that people could read it and stop asking her those redundant and sensational questions in every single interview. The questions induced flashbacks and reintroduced that loop of agony she had narrowly escaped. Of course, the book did not temper the press’s curiosity, and instead the questions became declarations—a Hollywood movie, a Broadway show, a constant punchline for Ike apologists, a casual branding iron engraving her most acute angst onto her new identity. Ike still possessed her. Meanwhile all of the women, including my own mother, who were enduring extreme violence now had Tina’s divine intervention, an archetype to look to amid their own set of lights and sirens. Maybe they would be believed, now that someone as famous as Tina had offered public testimony to similar experiences. When my mom escaped, with me and a pregnant belly, my own father, a musician who did cotton as a kid and made it so far past the field that he hallucinated traitors in those who loved him, it was after Tina’s book came out. Maybe the uproar it caused helped us and so many other families who had no context for themselves except their shared and hidden tradition of suffering and shining.

Tina Turner in Rio de Janeiro. Courtesy the official Facebook page for Tina Turner.

Tina had unwound a demonic glitch in American culture, and she’d broken the pact with trauma that glitch enforced. She was one of the great and brave whistleblowers. Weak men regarded her like a snitch, real ones with discrete reverence. Women did not have to cover for their abusers or die for them. Their children did not have to grow up witnessing this and at risk for reenacting the same dynamic in their adult lives. Suffering did not deepen intimacy or that toxic codependency so often mistaken for true love. It wasn’t long after leaving my dad that my mom took up meditation and chanting, too. Maybe Tina, who had used Buddhist mantras to shift her consciousness while still trapped with Ike, had inspired her, or maybe a new pattern had opened up in the universe, a path for women that had been lined with thorns and complicity before. Or was it that patterns of domestic violence had become as cliché to some jaded Americans as the legacy of picking cotton, just part of the tradition which relied on the threat of violence to justify its freedom obsession?

Tina Turner. Courtesy the official Facebook page for Tina Turner. Photo: Brian Lanker Archive.

Tina had the right to remain silent but her innate exuberance didn’t allow it. She could have taken her story into oblivion or translated it into the quiet knowing between words in the sutras and hidden it there, but she was too powerful to withhold from the world what it needed from her. The public’s distress fetish is not her fault. And in sharp flashes of textile-laced light, she managed to transmute that reputation for victimhood into one as the queen of rock and roll. She was the near-omnipotent star whose vocal tone could rake her lyrics across you like daggers or insistent calls for liberation. Life forced her to be harrowing, the little wing between the field, the stage, and the highway spanning an endless echo of her promising we don’t need another hero. By then she was screaming. With her, an era of unspoken trouble closed for a lot of women, and with it, the notion that black women did not sing rock and roll was also overruled by her post-confession music. She felt the R & B standards she was made to sing for all those years while touring with Ike were a record of a way of life that needed contesting. She wanted to tune herself to her fantasy of a carefree and playful existence wherein the stakes of mischief were pleasure and not death. Rock and roll gave her a double breakthrough and a new identity. She would carry the burden of being as well known for her suffering as for her singing, but she didn’t have any interest in continuing to sing about down-home love affairs that were all devotion, no romance. The arpeggios in those songs trembled like the bodies of battered women half the time, and the other half, the songs were so smooth they became instantly false, cold overwrought attempts at packaging soulfulness when you had lived through what she had.

Tina Turner. Courtesy the official Facebook page for Tina Turner.

In one live performance, Tina announces a song called “I’m Gonna Do All I Can to Do Right by My Man,” a recording on the Minit label, which was also my dad’s label in New Orleans. I imagine that all the men and women who did cotton were in a kind of regiment, teaching one another how to do songs, how to do tenderness, how to do love, how to do pain, and come up. I imagine them as children pretending the field is a recording studio and making up work songs through samples from their church choirs and trying to negotiate right and wrong from the vantage of a shell of blinding white light on a hostile night road. I was there alone, how can I tell you what alone meant? Tina says of her do-right years. But in fact she was a member of a tribe of men and women whom only she could name and empower to reveal themselves. What we owe her, she already granted herself when she started over. Her departure from this lifetime feels like a claiming of justice. Now her spirit can finish recovering without being nagged by retellings of the hardest parts of her life. And those who resent her for exposing their misogyny at the same time that she exposed a new kind of feminine daring get their problem back with one less woman to project it onto. Tina is the eternal fugitive, whom horror or grace chased out of stasis again and again because she belonged in the spotlight, because she needed to run toward it, because we needed to run alongside her. We let her disappear into the story of her troubled past sometimes, as if she was an alibi for our own truths. Now she is the skit of lights on our road revoking that alibi with her absence and we’re alone here, a fairy tale and a nightmare forever stitched together by the alert amber resin of her voice.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April, 2022.