Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

In a commemorative exhibition of the city’s cultural heyday, art is inextricable from its contexts.

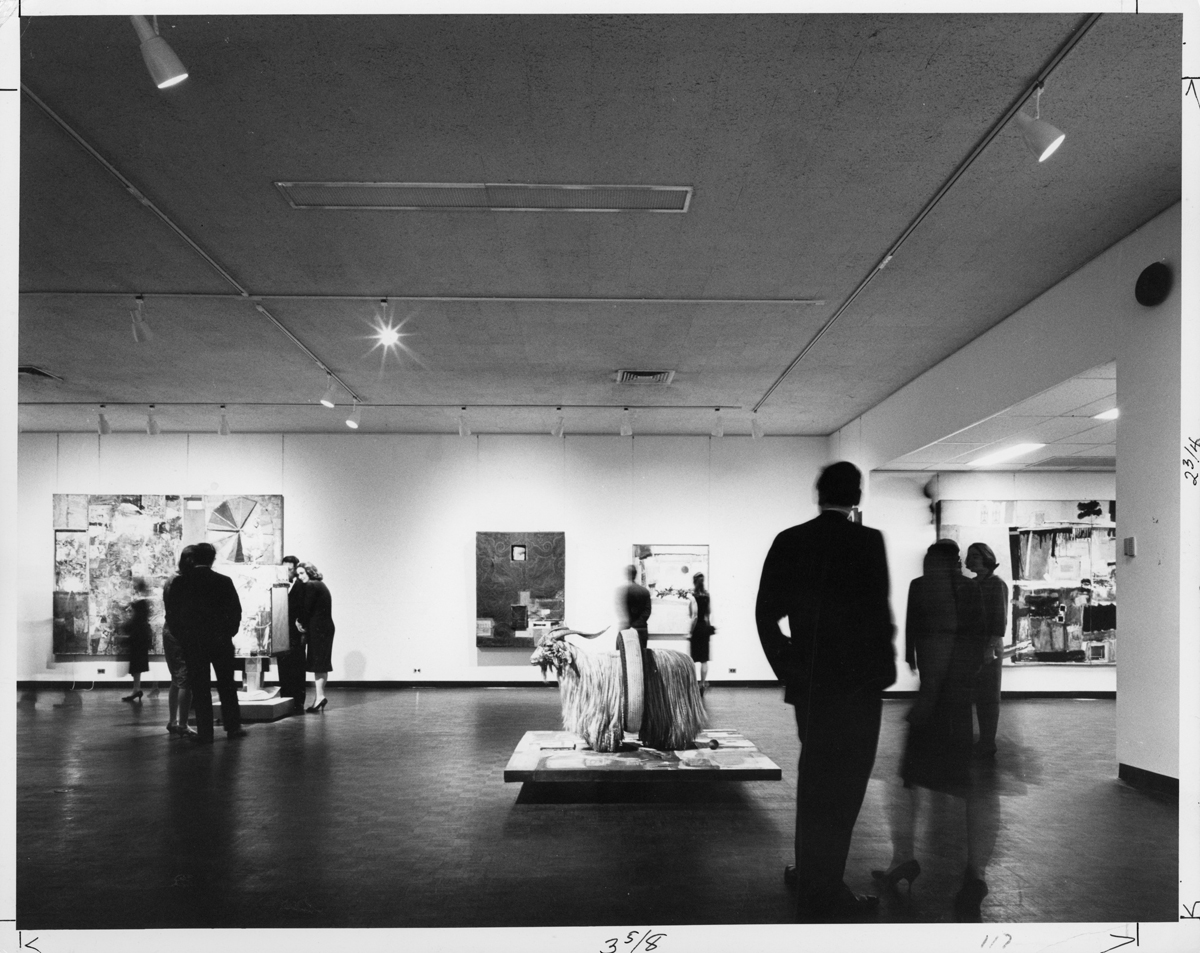

New York: 1962–1964, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Frederick Charles.

New York: 1962–1964, conceived and curated by Germano Celant, developed by Studio Celant with Claudia Gould, Darsie Alexander, Sam Sackeroff, and Kristina Parsons, Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue,

New York City, through January 8, 2023

• • •

To stage a show about art in New York between 1962 and 1964 is a bit like mounting an exhibition about Rome between 1508 and 1512, or Paris around 1872—it’s our golden age, our cultural prime time, what we want to be remembered for. The period commemorated in this exhibition, however, is not simply the epoch in which New York caught the world’s eye with its fecund mix of couture, contemporary art, and counterculture (the three ostensible subjects of this survey); it is also the moment in which the Jewish Museum itself, guided, in part, by the acumen of its farsighted director, Alan Solomon, helped organize these energies by staging startling exhibitions of then-wunderkind artists, namely Robert Rauschenberg (in 1963) and Jasper Johns (in 1964). Works by the two pepper the exhibition but, hung cheek-by-jowl not only with other artworks but also Rudi Gernreich’s monokini, an Eames lounger, groovy wallpaper, ersatz newsstands, and blaring televisions, they effectively disappear into the woodwork. The pieces that do stand out—Harold Stevenson’s very large 1962 painting of a human eye, James Rosenquist’s split-screen Sightseeing (1962), Kenneth Noland’s ocular Spread (1958, but included in a 1963 exhibition at the museum), and Marjorie Strider’s eye-catching pop relief Girl with Radish (1963)—all understand that, in order to grasp attention in a spectacular age, vision must be aggressively addressed.

Marjorie Strider, Girl with Radish, 1963. Acrylic on laminated pine on Masonite panels, 72 × 60 inches. Courtesy the Jewish Museum.

A life-size photo-tableau of Manhattan’s Eighth Street, Ye Olde Thoroughfare of Bohemia Past, welcomes visitors in an antechamber to the exhibition. In front stands a crossing sign, a liquor-store shingle, and a park bench. Upon entering the galleries you can play songs on a real live jukebox, including Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and the Ronettes’s “Be My Baby.” Here and there you find domestic dioramas, including a yellow kitchen counter decked out with a Betty Crocker cookbook and Mad magazines. In 1964, New York’s Bianchini Gallery staged The American Supermarket, which placed Campbell’s soup cans next to Warhol’s canvases, but the Jewish Museum experience reminded me of a more pedestrian place I used to go to as a kid called Cafe 50’s, where you ate greasy burgers and fries surrounded by Marilyn and Elvis tchotchkes. Squeezing an entire decade into a storefront, the joint was nothing like the 1950s, but that was part of the fun. Without intending to, New York: 1962–1964 shares something of this kitschy spirit. Call it the Pirates of Greenwich Village, an “E” ticket ride.

New York: 1962–1964, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Frederick Charles.

Despite its funhouse feeling, the exhibition raises important questions about art’s relationship to history. Art, of course, is made in different times and places, and while it inevitably speaks to such coordinates it also stands apart from them—that is why we continue to gaze at artworks made years, even millennia, in the past. (We don’t look at them, I think, simply to learn what happened.) But the headlined version of history delivered here boils complexities down into overly simplistic equations of art with context. Art has no chance to be different. In one instance, a televised discussion between James Baldwin and the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr about the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing plays above a series of intensely wrought steel Lynch Fragments by the sculptor Melvin Edwards. As important as each item is individually, it becomes impossible to consider the latter’s sufferance and opacity when you’re being told exactly what you should be thinking by the voices overhead. (Jack Whitten’s powerful Birmingham, 1964, synthesizes many of the exhibition’s strands by figuring history as an open wound.)

New York: 1962–1964, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Frederick Charles.

The artworks that break through New York’s canned quality are the freaks. Jim Dine’s fleshy Tattoo, from 1961, a Caucasian confection of oil paint, grabbed me with its gummy surface. The word “TATTOO” tautologically tears across the upper right-hand corner of the canvas, cutting off the final O. If Christianity’s innovation was to transform the word into flesh, 1960s New York turned painting into body. Painting became visceral, and dreamt of touching its audience. This is most evident in the work of performance artist Carolee Schneemann—she preferred the mantle “kinetic painter”—somewhat randomly represented here by a small Cornell-like diorama titled Butterworth Box II (1963). (Luckily her memorable Meat Joy, 1964, a teeming mass of bare bodies and dead chickens that gathered one night at New York’s Judson Memorial Church, screened in a related film program at Lincoln Center.) But a more traditional painting continues this corporeal thread: Martha Edelheit’s Tattooed Lady (1962), a depiction of a female figure bent in the shape of an inverted U. Her contortion, however, is not her only remarkable feature. As the painting’s title suggests she is covered in tattoos—butterflies, octopuses, hearts, mushrooms, the name “Davey Jones,” and an American Indian chief. Andy Warhol made a famous calling card around 1955 depicting a burlesque dancer inked with signs of American industry, including Ford, Greyhound, and Lucky Strike, but Edelheit’s vision is corporate in another way. Less pop, it brands the body differently—still as colonized territory, but also offering a possibility for play.

Martha Edelheit, Tattooed Lady, 1962. Oil on canvas, 45 × 50 × 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. © Martha Edelheit / Artists Rights Society.

To see all that, though, you have to edit out much of the noise from the surrounding historical artifacts. It’s not that artworks shouldn’t be installed next to non-artworks, of course, it’s just that they should form an argument and not get atomized into zeitgeist in the process. I’m not against cultural history per se. It’s interesting to consider how the lox-and-bagels version of postwar American Jewishness always carried the vanguard taste of Rauschenberg within it, but even this is to reduce artworks to placeholders. Art belongs to culture but is not subsumed by it, and luckily we have technologies besides scenography to map the relations between the two: a handsome broadside of a catalog and accompanying film programs at Lincoln Center and Film Forum create a dynamic constellation joining the works on view to the histories animating them without either getting smothered.

The opening of Robert Rauschenberg at the Jewish Museum, March 31, 1963. Artworks © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society.

Leaving the exhibition, I performed a thought experiment: How would one stage New York: 2020–2022? Install a mock–Apple Store with a Wade Guyton ink-jet painting? Replicate the graffitied plywood of a shuttered SoHo storefront during the raging days of BLM alongside a painting that nods obliquely to racial politics? It seems we need some better way of facing off art and history. Art doesn’t simply reflect its time. It doesn’t simply belong to it. It responds to it, yes, but it also reformulates it, shows it differently, offers respite from it. An exhibition might do that, too.

Alex Kitnick is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.