Yusef Komunyakaa

Yusef Komunyakaa

An expansive multidisciplinary exhibition by Shezad Dawood, inspired by the late jazz composer Yusef Lateef’s 1988 novella.

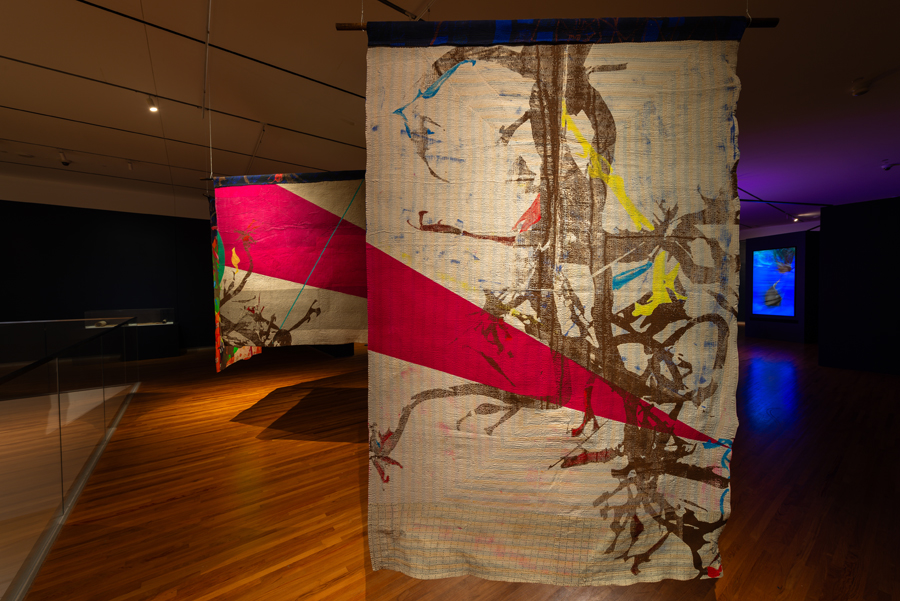

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, installation view. Courtesy Aga Khan Museum. Photo: Aly Manji. © Aly Manji.

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, Aga Khan Museum,

77 Wynford Drive, Toronto, through May 5, 2024

• • •

Shezad Dawood’s exhibition Night in the Garden of Love cultivates a zone where imagination flourishes, where images collide with the tactile to create tension, optical illusion, movement, and exploration. Through this multidimensional, multimedia installation, Dawood collages the space together in an extravagant collaboration with artists working in tactile forms such as fabrics, ceramics, and paintings, as well as ethereal forms, such as scent, sound, movement, and virtual reality. His curatorial performance is born from his vivid encounter with Yusef Lateef’s experimental novella, published in 1988, Night in the Garden of Love.

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, installation view. Courtesy Aga Khan Museum. Photo: Aly Manji. © Aly Manji.

A poet knows the reader is always a cocreator of meaning. Here, Dawood’s reading of Lateef becomes reenacted in a performance of his own interpretations, executed with many artists as an offering to visitors who now become performers and experiencers of Dawood’s creation. How did Dawood become captivated by Lateef’s novella—the emotive vehicle for his latest art endeavor? I imagine that Dawood asked questions of Night in the Garden of Love not merely to interrogate, but to plumb the narrator’s heart until it speaks.

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, installation view. Courtesy Aga Khan Museum. Photo: Aly Manji. © Aly Manji.

This multidimensional work appeals to the sensory body while remaining in this tactile world and simultaneously in a futuristic one. This convergence of reality and futurism is already at the center of Lateef’s novella. And, perhaps, Lateef’s aesthetic activates the sensory imagination for the reader. Like in most of literature, the garden is a metaphorical one, but for Lateef the garden seems to arise out of a dream; Dawood’s garden, too.

Yes, there is an opera in the pages of Lateef’s work, and Dawood’s translation seems to directly access this energy. At first it may seem difficult to think of the novella as a libretto, with the latter’s lyrical grist and muscle. But as one reads, questions grow into active query, and this is what ignites imagination, which becomes bedrock beneath a good idea. Dawood gives Lateef more than a bow of his head. From what may seem somewhat abstract, the visual artist creates the true furniture of a stage through ideas grafted from the novella. Within the staging, the seeds of mind flourish. Dawood even gives life to imagined plants arising from algorithms. At the end of Lateef’s novella, the reader is given this exchange:

Cafarelli (whom the author says is actually himself): “Fall rain of love, release the love from within.”

Then the Turbaned woman says: “Let your garden grow.”

Finally, the Mutant declares: “Send up tidings of the heart.”

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, installation view. Courtesy Aga Khan Museum. Photo: Aly Manji. © Aly Manji.

When Lateef, and by extension Dawood, gives glimpse of fantasia, a state of mind, where do we travel, and what do we see? Does it live only in the imagination, or in the real world as evidence of a life-changing voyage? Is Night in the Garden of Love more than a dream?

No, it is not a dream. Perhaps Dawood gives us an objective lesson. His ideas assume shape and weight. But also, I feel, this visual artist has created more than paraphernalia for the stage—more than a set and costumes. Perhaps Dawood’s work proclaims that there’s an opera to go onstage. Though he has chosen to incorporate the talents of collaborators, the images and wares also continue to be touched by the lyricism of Lateef’s language and vision. And, in this sense, the art-objects concretize this unique frame of an idea through its execution. Some may see this as a mechanical illusion, but in its overall dimension, it is a stroke of genius. The garden of mind manifests. And this thinking outside of the box goes back to how Lateef’s half-hidden libretto slowly reveals itself as a real, breathing idea with creative sway and gravitas.

I can almost hear Dawood saying this: “Aw! If Yusef could see Night in the Garden of Love as an opera, I can see my artmaking as his stage set!” Of course, I am putting words in this artist’s mouth, but I feel that I am not far off. Now, perhaps, is the ideal time for Lateef’s Night in the Garden of Love to come alive through art dedicated to a shared vision that embodies a unique fantasia within the visual arts, language arts, and definitely music—a personalized poetry that dares universal concern for humanity at large. The attention to nature and recycling centers in the novella cannot be overlooked or shortchanged in the shared vision of Lateef and Dawood. The artwork grounds the language, holding intention and attention in place, each giving to the other.

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, installation view. Courtesy Aga Khan Museum. Photo: Aly Manji. © Aly Manji.

This is a unique collaboration in the arts. And, yes, the technology can travel numerous places at once. But, in this troubling sense, the pragmatic might ask, does installation art have the power to inspire change? Nature is the heart-beating topic, but is its process natural, tangible? Am I being selfish when I proclaim that I want to see and feel the real opera! No, I do not wish to walk away from the garden with an electronic buzz in my head. But, at first, maybe I missed an important fact. Yes, Night in the Garden of Love is inevitably an opera for this time we are living in. If one thinks about the exhibition, the lively imagery and hues and its daring use of virtual reality, we shouldn’t be surprised that Shezad Dawood is bridging traditions of the past—for instance, working in fabrics—with media of this digital age. Yet I would argue that his garden does not bear the symmetry of the wild; still, in Dawood’s presentation, a tree or thick vine would never grow around a strand of barbed wire.

Why does it feel that Dawood’s Night in the Garden of Love extends multiple possibilities—growing or diminishing, changing like an improvised jazz composition? And, of course, this propels one to think of the fact that a real garden seems always changing because of natural elements. It is never totally static—truly an act of becoming. There are seasons growing and/or diminishing. Did it all sprout with emotion in the air? Did Dawood know that he would bring Lateef’s actual paintings into his Garden? And when did this Garden begin to possess feeling or possibilities of expansion? Of course, his made plot is an act of public art that is in motion—in spirit and execution. One may go back to Lateef’s novella, where he mentions saxophones numerous times. Some horn players possess the ability to create a seance of voices. Could Charlie Parker’s “Birds of Paradise”—which Lateef notes—possess a hint of opera? Do you think this exhibition will change here and there, floating with the freedom of an improvised composition, a carefully cultivated but ever-changing garden?

Shezad Dawood: Night in the Garden of Love, installation view. Courtesy Aga Khan Museum. Photo: Aly Manji. © Aly Manji.

I was surprised to learn that Lateef, a flutist whose musical compositions I have loved for decades, had penned a novella. Dawood seems to engage Lateef’s vision from the inside. In fact, Dawood seems a seer; from the onset, this artist knows how to tease out and accentuate Lateef’s half-hidden libretto. Dawood seems to have tuned into the creative pulsebeat (musical, lyrical, and experimental) inside Lateef’s writing. The visual artist taps down to the paydirt of what surprises. Perhaps the writer’s language influences the vision the artist arrives at. Yes, the language on the pages would make the mutant at home—in a land of insinuation. In fact, the artist seems to step slightly out of character to give us (or himself) glimpses of the fantastical. Colors, textures, nuances, techniques all collaborate to give the artist mastery over vision. And the viewer is beckoned in to engage each piece. In fact, signs should say: Please Do Not Touch. Dawood’s rendition seems to unearth the opera that I surmise Lateef may have staged in his head. The conversation that emerges between Dawood and Lateef is truly a singular, probing engagement—a personalized visual entanglement that brings light to a world between worlds.

Yes, indeed, bring on the lovers, the musicians, the singers, and the dancers. Let there be ample space on the stage. Dawood’s creations bring his vision into the space with deep precision.

Yusef Komunyakaa’s numerous books of poems include Talking Dirty to the Gods; Thieves of Paradise, a finalist for the National Book Critics Award; The Chameleon Couch, a finalist for the National Book Award; Neon Vernacular: New & Selected Poems 1977–1989, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award; and Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth: New & Selected Poems 2001–2021. Komunyakaa’s prose is collected in Blue Notes: Essays, Interviews & Commentaries. He also co-edited The Jazz Poetry Anthology. In 1999, he was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. He served as New York State Poet 2016–18.