Janet Kraynak

Janet Kraynak

Powerful works of activism and political critique showcased in

a long-overdue retrospective.

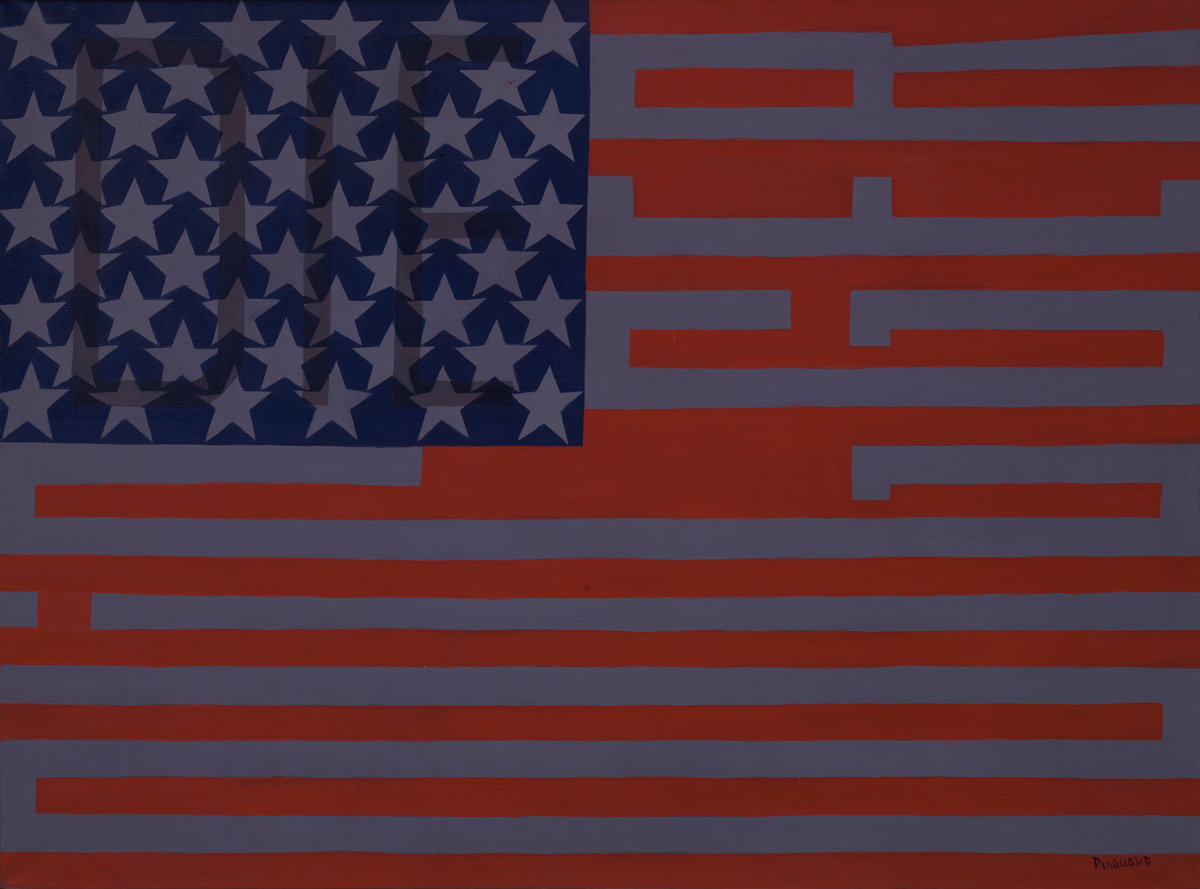

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding, 1967. Oil on canvas, 72 × 96 inches. Courtesy ACA Galleries. © Faith Ringgold / ARS and DACS.

Faith Ringgold: American People, curated by Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari, with Madeline Weisburg, New Museum,

235 Bowery, New York City, through June 5, 2022

• • •

The first image one sees in Faith Ringgold’s current New Museum retrospective is a self-portrait of the artist. Executed in 1965, the picture features the telltale palette of Ringgold’s early paintings—rich browns and umbers, deep blues and reds—as well as her experimentation with form: what is often (casually) called figurative, but what the artist calls “Super Realism.” Lying beyond any stylistic affiliation, Ringgold’s terminology alludes to her paintings’ analytical drive over and above mimesis. It is an approach that, for decades, would leave Ringgold on the margins of the art worlds (the plural here intentional). Inserting herself as an artist and activist into official art spaces was a lifelong quest. The occlusion that her self-portrait here symbolically corrects announces that she finally has earned a rightful, central place in the museum—in 2022, sixty years into a prolific and groundbreaking career, and almost forty years since her art was last granted a large-scale exhibition in the city that she long called her home.

Faith Ringgold, Early Works #25: Self-Portrait, 1965. Oil on canvas, 50 × 40 inches. Courtesy ACA Galleries. © Faith Ringgold / ARS and DACS.

Belatedness, if I can summarize it this way, is a feature that says a lot about Ringgold’s art as well as her career. On the one hand, it points to the many obstacles she has faced, resulting in the delayed reception of her work. With a stated commitment to the canvas, Ringgold was an outlier with regards to the mainstream art world in the 1960s and ’70s. During that period, much of what was classified as avant-garde tended toward the sculptural and performative, moving decidedly away from painting, which was rejected as a moribund, if not politically anti-progressive, medium. At the same time, her outreach to artists affiliated with the Black Arts Movement—which celebrated figurative painting’s communicative potential—were occasionally equally thwarted. Romare Bearden, a founding member of the Black collective Spiral (“the old men of Black art,” as painter Vivian Browne dubbed them), dismissed Ringgold in what can only be described as a patronizing fashion. As Ringgold recalls in her memoir, such instances were indicative of the patriarchal attitudes she perceived more broadly speaking, even in Black artistic and political circles: “For me the concept of Black Power carried with it a big question mark. Was it intended only for the black men or would black women have power, too?”

At the same time, belatedness refers to the force of Ringgold’s artistic critique, which consciously mines history in relationship to the present, rather than rejecting the past as a closed chapter. The artist’s engagement with aesthetic and cultural modernism—developments that span early to mid-twentieth century—has been both consistent and overlooked, yet under the banner of decolonization it has finally gotten a hearing. Recent social reckonings have led to a reassessment of the holes and hierarchies that long have plagued art history and the museum. Indeed, this process is nowhere better exemplified than by the Museum of Modern Art’s very recent (2016) and, as such, woefully late acquisition of Ringgold’s monumental 1967 mural, American People Series #20: Die, along with its prominent display adjacent to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon—a pairing that, in the reception of the museum’s reopening in 2019, came to emblematize the latter’s entire reinstallation.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die, 1967. Oil on canvas, two panels, 72 × 144 inches. Courtesy ACA Galleries. © Faith Ringgold / ARS and DACS. Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource.

The New Museum retrospective, deftly organized by artistic director Massimiliano Gioni, curator Gary Carrion-Murayari, and curatorial assistant Madeline Weisburg (full disclosure, a former student of mine), is both timely and propitious. The exhibition rightfully gives prominent place to Ringgold’s early paintings, including the magnificent American People Series (1963–67) and Black Light Series (1967–69), both of which occupy most of the second floor. In these works, the artist’s subtle but searing analysis of America’s racial disparities and violence are expressed in stylized color and form. Die—whose subject is the spate of resistant uprisings, commonly called “race riots” during the 1960s—comprises a cacophony of bodies scattered akimbo, limbs flailing, while weapons and blood spatters abound. The Black Light Series banishes the color white, foregrounding a darker palette, while incorporating African motifs and references. (Taken by a Black artist of the African diaspora, the act is a clever inversion of modernist appropriations of African art.) In several, the “n-word” explicitly appears, operating both as signifier and formal pattern. The confrontational nature of the language remains shocking to see in a museum, an institution that in many cases (think the recent Guston affair) has become timid and fearful of courting any potential controversy, leading to regrettable instances of self-censorship. Ringgold’s art, however, is unsparing in its critical acumen, made more acute by the sheer lusciousness of its surfaces, so that the viewer is drawn into its field while implicated in its meanings. Escapism is not an option.

Faith Ringgold, Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger, 1969. Oil on canvas, 36 × 50 inches. Courtesy ACA Galleries. © Faith Ringgold / ARS and DACS.

Display cases of archival documents, as well as graphic works and collages dedicated to various progressive causes (i.e., the Black Panthers and the prisoners in the Attica uprising, from 1970 and 1972, respectively), testify to Ringgold being a central actor in art-world activism of the 1960s and ’70s. Among the many groups to which she belonged (and some of which she cofounded) are the Art Workers’ Coalition, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, Where We At, and the Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation. She also was one of the so-called “Judson Three,” with Jon Hendricks and Jean Toche (of Guerrilla Art Action Group fame), who were arrested for desecrating the flag during the 1970 The People’s Flag Show at Judson Memorial Church.

Faith Ringgold: American People, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Intersectional before the term was coined, Ringgold’s coextensive painterly and protest activities explore the ways that Black women were left out of both the civil rights and mainstream feminist movements—an exclusion parallel to their lack of entry into the museum. The exhibition weaves a Black feminist thread throughout. One sees it in the 1971 mural For the Women’s House, located until the show’s opening at Rikers (soon to be on extended loan to the Brooklyn Museum), as well as in the fabric paintings she began making in the 1970s, which—as the artist quips in an interview with Gioni for the show’s catalog—were easier to carry around and exhibit across the country as “nobody wanted to pay for shipping.” These un-stretched works, some based in narrative, others abstraction, include the famed story quilts Ringgold began creating in the early 1980s. Also of note are her literary forays into children’s books, including the acclaimed Tar Beach (1991), whose stunning drawings are given their own room in the exhibition.

Faith Ringgold: American People, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

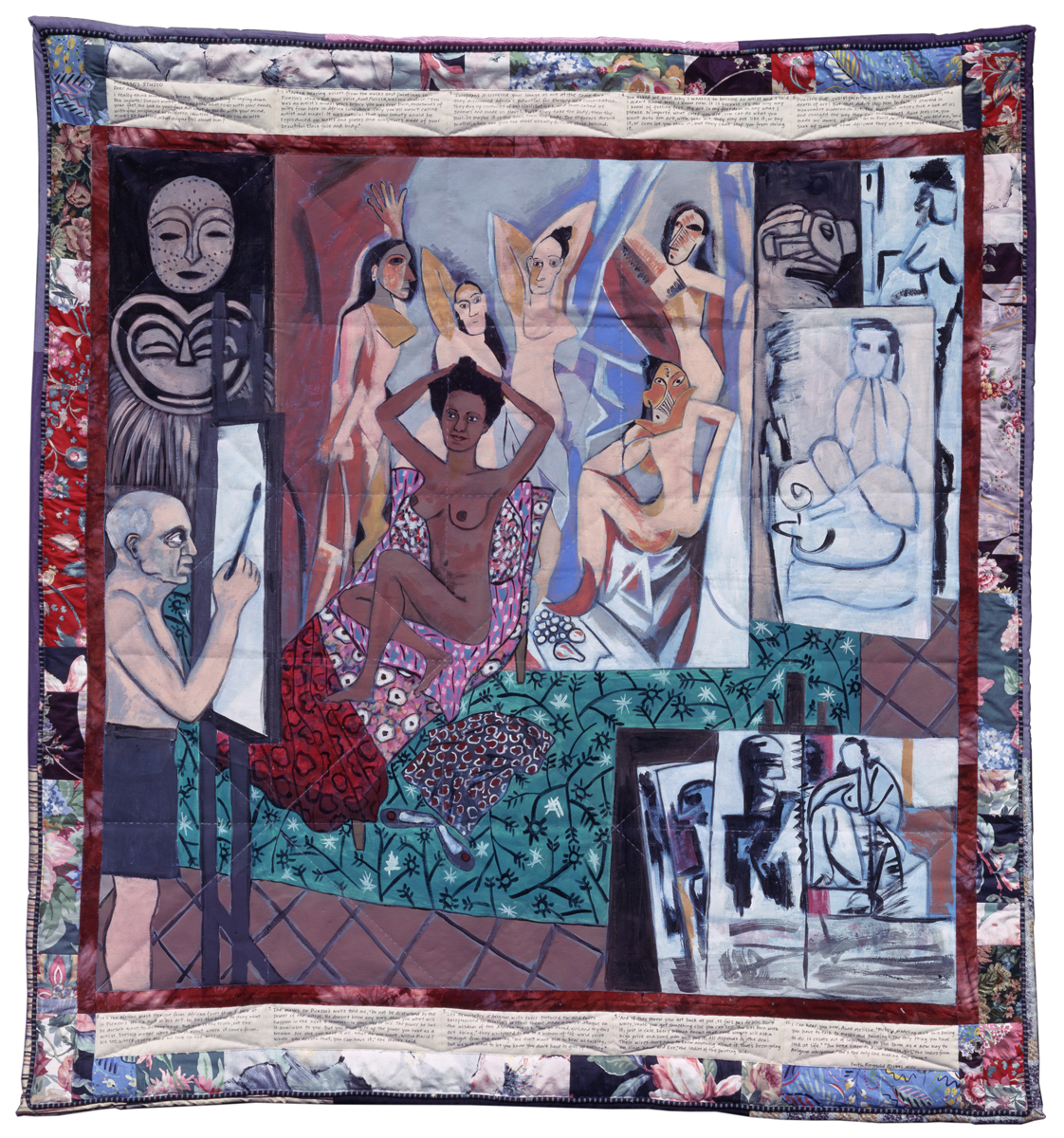

Embracing artistic materials long deemed domestic or craft-like (a not-so-subtle gendered encoding), Ringgold experimented with tactics of figuration, text, narrative, and, importantly, appropriation: not only painting herself into the history that continually sought to exclude Black women but also forcing a reassessment of that history and how it has been recorded. As scholar Homi K. Bhabha has written, mimicry is a tool of the disempowered, operating as a resistant mode of delay. Evidence of this strategy abounds, most expressly in her monumental tapestries, The French Collection series (1991–97), here displayed against walls painted a jewel-like, saturated blue. In them, Willia Marie Simone, Ringgold’s alter ego, frequents the fashionable artistic sites and circles of early twentieth-century Paris: visiting the Louvre, lounging at an all-women picnic in Giverny, attending Gertrude Stein’s private salon, and posing in front of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles in his studio. Grand in scale but precise in intimate detail, including scrolls of text lining the edges, these images are a visual feast to behold.

Faith Ringgold, Picasso’s Studio: The French Collection Part I, #7, 1991. Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed pieced fabric, ink, 73 × 68 inches. Courtesy ACA Galleries. © Faith Ringgold / ARS and DACS.

Referring to America, Ringgold comments, “It’s a colorful place, so to speak—never a dull moment.” Color, like shape, we can infer, has never been a formal quality alone. Rather, it is the stuff of tension, controversy, battles both big and small. Yet echoing her modernist forebears, who sought in aesthetics a utopian sense of political possibility, Ringgold’s art refuses to abandon hope. “I am never discouraged,” she tells Gioni. “I think we are going to be all right.” Ringgold’s optimism, a quality in short supply during these challenging and cynical times, provides a welcome respite: a glimmer of possibility in color and form.

Janet Kraynak teaches in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University, where she is also the director of the MA Program in Modern and Contemporary Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies. Her most recent book, Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life, was published by the University of California Press (2020).