Sowon Kwon

Sowon Kwon

Bruce Nauman walks the walk at the Philadelphia Museum.

Bruce Nauman, video still from Contrapposto Studies, I through VII, 2015/2016. Image courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York. © Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society. Photo: Erika Schoof.

Bruce Nauman, Contrapposto Studies, I through VII, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, through April 16, 2017

• • •

In 1968, the artist Bruce Nauman constructed a long and narrow (twenty feet by twenty inch) corridor in a borrowed Long Island studio. He then videoed himself walking inside it, while approximating and animating the contrapposto pose. Developed in classical Greek sculpture, contrapposto describes a torqueing of the human figure such that the axis of the shoulders contrasts with those of the hips, depicting a naturalistic distribution of weight in an idealized body. In Contrapposto Studies, I through VII, a new suite of installations currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Nauman revisits this seminal performance and video, Walk with Contrapposto, in digital media.

Five HD video projections make up the installation in the main room. They show multiple moving images of the elder Nauman, his head cropped at the eyeline or jaw, and wearing a quotidian white T-shirt and blue jeans, repeatedly walking, pivoting, and turning as he did forty-eight years ago. The videos run concurrently on two facing walls—two on one, three on the other—in a continuous loop.

The framing of each repeating figure of the artist is stitched side to side and stacked in two rows to fill a long expanse, like a monumental processional frieze in video form. On the top row, a digital filter has inverted the footage to a different color palette, one resembling photographic negatives, and the motion is reversed so that the figures seem to walk backward. The camera also moves (unlike the fixed perspective in the original WWC), keeping pace with Nauman so that even as he walks, he remains central within the frame. The horizon line may shift, but the scale of the figure remains constant.

While Nauman’s figure is multiple and the walk repetitive, each frame is also discrete, with variations in movement. You might catch one figure take a longer pause than the others as if awaiting a cue; another drops his arms or momentarily disappears at a point of edit, or briefly walks off screen. Some frames are bisected, with one layer moving out of sync with the other, sometimes so much so that legs move disconcertingly in the opposite direction of the torso. In the two larger studies, the rows are further subdivided into fourteen strata. The fragmentation and disjunction this creates is jarring at first, then mesmerizing, as the fractured body mis-registers, lags, then catches up to itself briefly, abuts itself partially, then again falls in and out of alignment, again and again, from head to toe. The corresponding audio, an ambient rumbling with cavernous echoes, punctuated by tinny swishes and regular thuds, is made up of the shuffling of feet or incidental studio noise, which has undergone comparable digital manipulation in sound editing.

The fragility of the body and its inevitable dissolution is one read. Another might note the poignancy in a rumination on the nature of subjectivity as split, provisional, and multiple, and fracture as constitutive of self. Still another might suggest that we are all disintegrating and reintegrating over and over again, with all the cumulative wear and tear therein. And most of us know something about the absurdity—and yet the persistence—of the exercise of pushing ourselves into the contours of idealized form. But such interpretations fall short in accounting for the boldness and energy in the work, and the dynamism in its skillful mixing and recombining of a singular sequential action. So, fragile but also resilient. Poignant but also dazzling.

Bruce Nauman, video still from Contrapposto Studies, I through VII, 2015/2016. Image courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York. © Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society. Photo: Erika Schoof.

The exhibition continues in a smaller gallery nearby, where two more studies of four figures, each walking front to back, are projected on opposite walls. One set is inverted and reversed. In “negative” the hue of the jeans is weathered yellowish, more Carhartt or Dickies duck cloth than Wrangler’s denim, but could still pass for cowboy wear in a pinch. The dark indigo tint of the rest of the image, though, summons the night and black bodies with hands above their heads, and the pose you assume when scanned at the airport, or when being arrested and detained. Something I have wondered about for a while: Art Make-Up, No. 4, a film (not on view at the museum) in which Nauman paints his upper body and face with black theatrical makeup for eight minutes, was made the same year as WWC, the year of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination and the passage of the Civil Rights Act. To what extent does Nauman put in tension the political ramifications of aesthetics and form with respect to race? Was he moved by moral imperative at the time, or was he more cavalier? And what of the privilege of having that choice?

The original Walk with Contrapposto is also on view in an adjacent gallery. Unlike the gallery with the new works, the setting here is small and enclosed, with a lone television monitor powered by (simulating?) outmoded cathode ray tube technology, humming and flickering, almost as if in a time capsule. In the video, the camera is mounted above as in surveillance mode, and the stride of the artist as a young man is longer and more assured, his hip tilt more pronounced, as he paces forth and back to the steady clunk of work boots for one hour, the length of the recording capacity of the Sony Portapak, the latest in prosumer video equipment at the time. The decidedly domestic scale of this installation (with sofa-height seating) also makes it enticing to try to envision the world on the verge of watching another walk in grainy black and white, the walk on the moon, and the one small step/giant leap that would embolden and inspire generations to come.

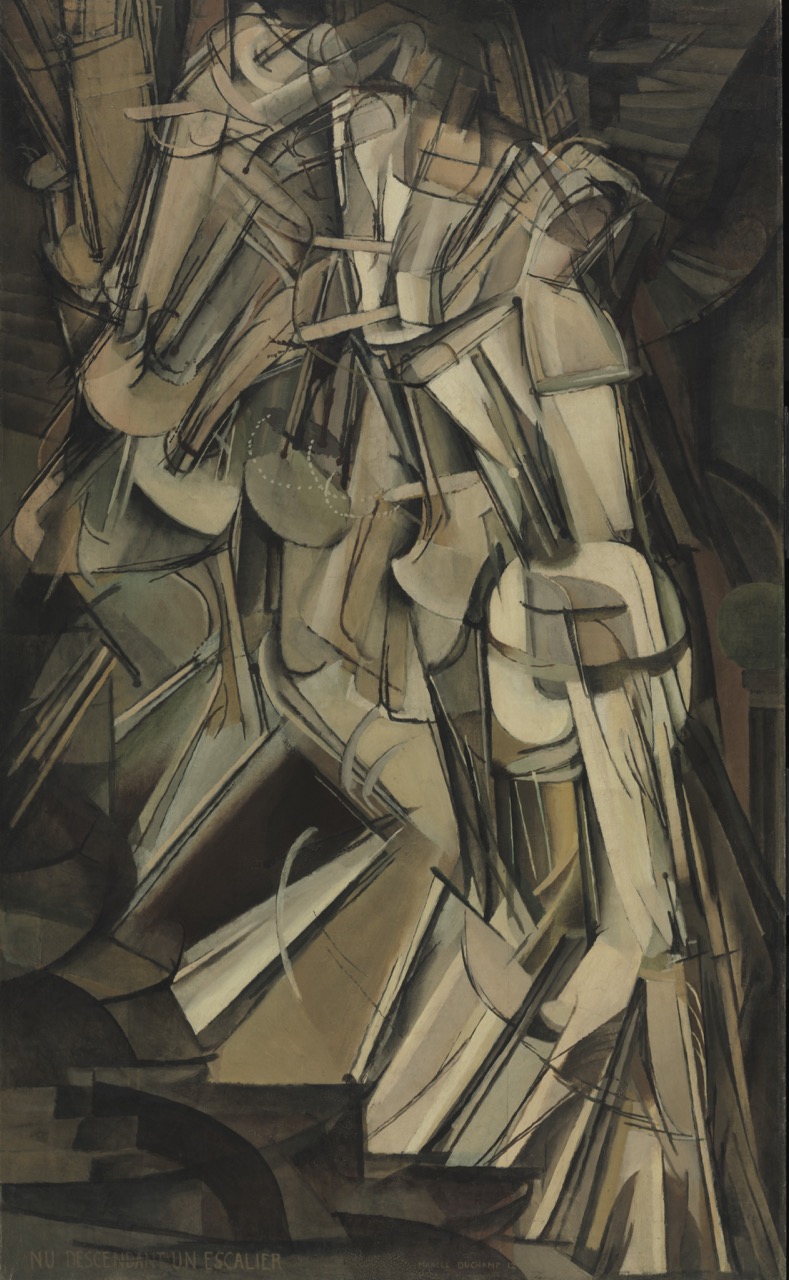

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2016.

There is a fortuitous resonance in the fact that the Philadelphia Museum is also home to Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912), the modernist painting par excellence in imaging the body in motion. Duchamp’s work crystallized the influences of the futurists’ embrace of speed, mechanization, and “universal dynamism” and cubism’s fracture/synthesis of form, as well as the technological innovations of the time, such as cinema and stop-action photography. Scholars say that the ancient Greek sculptor Polykleitos too, through contrapposto, sought to imbue the figure with vitality (an organic vitality as opposed to the machinic in Duchamp) and the illusion of past and future movement.

Perhaps it is a stretch and a bit fanciful to suggest that the subtle balance achieved in the Kritios Boy or David, or the anguish and pathos of Laocoön and sons, could be in dialogue with the digitally mediated presence of an aging North American artist in the twenty-first century. But this exhibition movingly invites reflection on the power of continuity in an individual practice, as well as its potential place in a larger historical project. Perhaps I am on no surer ground invoking Janus, the ancient Roman god with two faces that look forward and back simultaneously, as he presides over beginnings and endings, time, and passages. Most representations of Janus feature the head, disembodied and/or cropped, or he is seated. I will imagine him walking.

Sowon Kwon is an artist based in New York City. Her recent work includes contributions in Triple Canopy magazine and Broodthaers Society of America. She is currently working on forthcoming projects with Full Haus in Los Angeles, CA, and Gallery Simon in Seoul, Korea. She also teaches in the Graduate Fine Arts Program at Parsons The New School.