Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

Round and round it goes: the artist’s installation takes a pilgrimage to the existential state of not-knowing.

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

Candice Lin: g/hosti, Whitechapel Gallery, 78-82 Whitechapel High Street, London, United Kingdom, through March 1, 2026

• • •

There is a story and the story is a circle, or maybe a spiral, without distinct beginning or end, and the story encloses you, turns round and round, continues and starts again, and the story is a parable, or a fable, or a fairy tale, set in the special, oneiric time specific to that genre, but which these days seems to spill and unspool its non-time time, its strange limbo and deferrals, into the very real present and the unspecified future, disorienting, not like a magic trick but a spell or a curse or a haunting, although it is possible that to turn round and round is not necessarily a futile repetition, but a pilgrimage to the existential state of not-knowing, the discomfort of the story without conclusion: it keeps us going, in any case, even in the worst of times, doesn’t it?

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

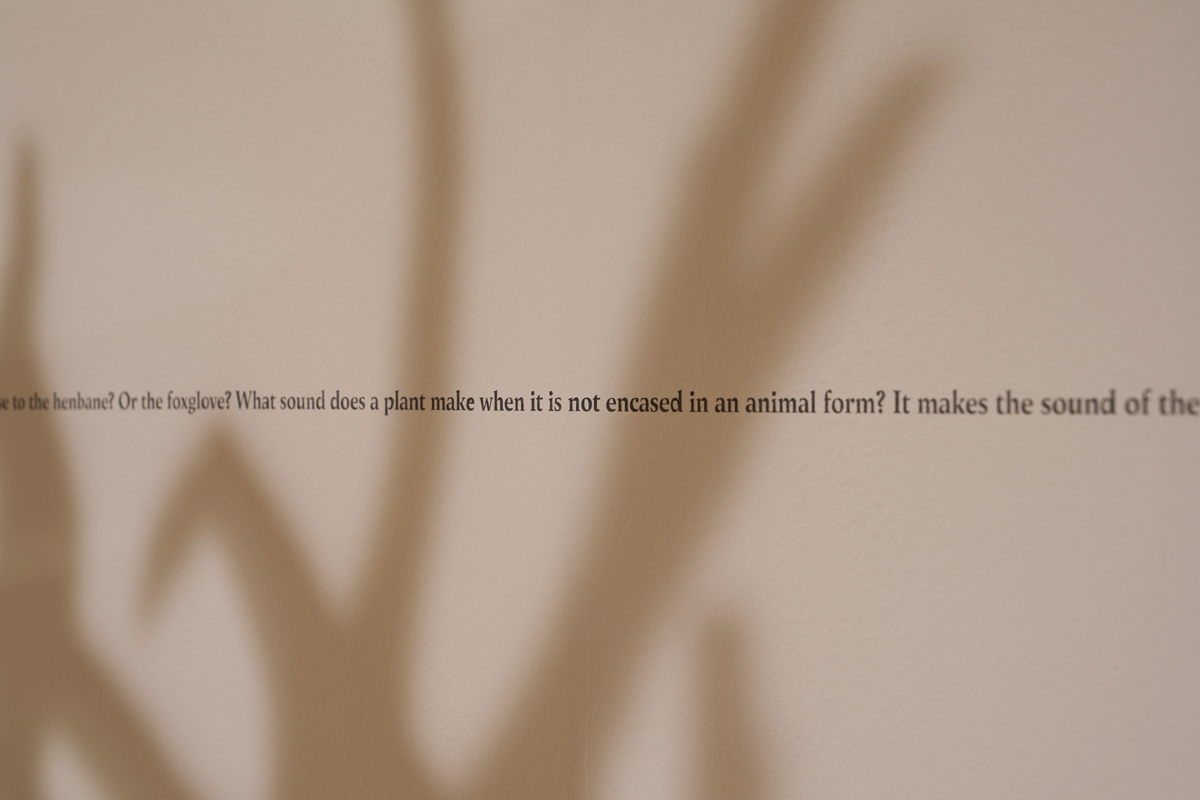

Around the white walls we read of a man, who has nothing, ventures into the world seeking sustenance and shelter. He encounters at first inanimate objects (a napkin folded into the shape of a skull: “death,” he calls it and puts it in his pocket), and then a succession of animals—a dog, a bigger dog, a rabbit, a bird, a bigger bird, a cat, a bigger cat, and this bigger cat brings him a wife, while the birds have already built him a house, and food and gold and other fortunes big and small have appeared, there’s just one small catch: they are all plucked from his body as tumors before they transform into something fantastic, each one leaving a gaping wound behind. Inside this story, which is also more than one story (halfway through, the man is replaced by an “I,” who seems to have lost a “you,” and probably more, but dreams, like the nothing man, of how to transform experience into images), we find ourselves within an actual (physical versus psychical) spiral, or a version of “nested circles within circles,” which is one of the phrases the Concord-born, LA-based artist Candice Lin has used to describe her labyrinthine installation, titled g/hosti.

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view (detail). Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

Lin’s work often traverses the micro and the macro, the specific and the universal, not so much combining as collapsing or exploding their binaries into multilayered, immersive installations in which materiality contains multitudes. A smell, a substance, a taste, a touch, a sound carries more than it seems, and all five senses are folded into the activity of image-making. (You see, I had to travel through at least two paragraphs of rippling layers before I even got to the artist’s name, although her practice is, at any rate, sui generis.) g/hosti is no departure, even its title a kind of capacious carapace: neither ghost nor host, it is each at once, and together they are at least one of the earliest versions of the word “guest,” which originally meant both “a person who is invited to visit someone’s home, or to attend a particular event or social occasion” and “a person who is unknown, a stranger.”

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

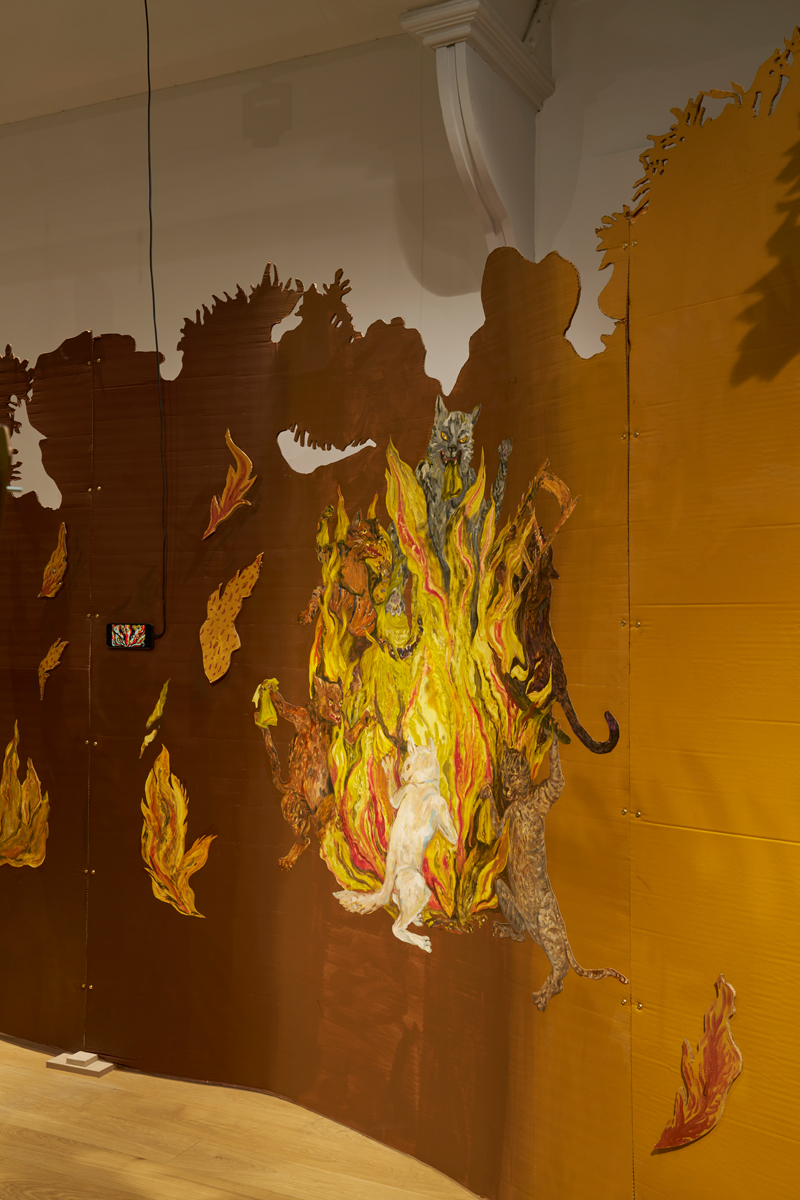

A later version of the word (Victorian versus Old English) means “a parasitic animal or plant. Cf. guest-fly,” first used in Dr. Thomas Spencer Cobbold’s Entozoa (1864), a now obsolete taxonomy of parasitic worms. “In the case of the adult worm,” he writes in his extensively illustrated study, “the happiest cures are readily affected by the expulsion of the ‘guest,’ but as regards the larvae the case is very different.” It was this eerie (expel the guest!) and infrequently used form of the stuttering ghost-host-guest hybrid, with its funny uptick i like a cartoonish afterthought, that turned around in my brain like (pardon the coincidence, this really is the correct term) an earworm as I wandered through Lin’s winding installation—a curling cardboard labyrinth covered with fantastical and sometimes terrifying painted scenes of animals and humans, or their remains, in exchanges so logic-defying they seem, for me at least, to demand the projection of hallucinatory narratives.

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

A wolf, yellow eyes flashing, prowling in long grass. A disembodied cat arm crudely holding up (pointing to? Can cats point? [what can’t they do!]) an iPhone. A skeleton arm holding up a raw steak from which spouts a tiny flame. Cats gathered around a table on which sit glass canisters of something yellow, possibly glowing. Dogs tearing apart a stag, its head wrenched back in agony. A skeleton about to be fucked by a dog or a wolf. The situation reversed. A bird, a strawberry, a hanging frog, a crucified cat, a lonely little school desk surrounded by abstruse symbols. This is a syncretic atmosphere of rich imagery at once recognizable and just harrowingly out of reach. We don’t imagine animals this way, though we know humans, animals too, are capable of much worse.

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view (detail). Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

g/hosti is striking in that its nonhuman figures, who seem to stand and walk and act with autonomy, even impunity, do not seem anthropomorphized but like actors in a passion play, putting on a great tableau for their guests—us viewers—who enter the space of the gallery from likewise troubled times. Lin has said that this work emerges from the contemporary context of American politics, including its protracted investment in the genocide in Gaza that has been livestreamed by its victims for more than two years. Short animated videos play at various twists and turns of the labyrinth, affixed to its flimsy but vivid walls, their soundtracks overlapping long before and after they are viewed. Sounds of protest, chanting, conflict, yelling, something fearful, filled with rage. Fires blazing. Crackling and heaving and then, funnily enough, the absolute banger Underworld anthem “Born Slippy”—she said come over, come over, she smiled at you boyyyyyyyy.

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

On the screens themselves the images match what we hear—bodies fighting, houses and forests on fire—but like everything in g/hosti they shape-shift seamlessly into something else: a butterfly, a dog that becomes a snake, an ouroboros that shatters into bones that then become protestors. Lin has described these animations, which require hundreds of drawings per thirty seconds, as a kind of solace: the act of giving shape and contour to a complexity of context and experience that otherwise overwhelms with its shapeless unease—too close, too hot, too ugly to understand. “Maybe this is similar to the act of prayer,” she says in the catalog in conversation with the writer Lucy Ives. “In drawing, you are witnessing: I see this, I feel this, I labor to trace the outlines of these gestures, these bodies, these people, these landscapes; it feels like doing something, though of course it’s not, really.”

Candice Lin: g/hosti, installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Matt Greenwood. © Above Ground Studio.

Amid so much wasted energy in the contemporary (shudder) “discourse” about art and politics, Lin’s work captivates with its bold, disturbing, elegant material summation of politics as a practice, as a way of seeing and making that struggles with its realities, its longue durée, its not-knowing—as opposed to politics as a set of ideas or a perfectly formed assertion, a posture, a demand, a thing somehow outside of us to be studied and contained rather than lived. As if we have a choice. We are the guest, the host, and the stranger, the worm to be expelled. “Without knowing it: life,” reads one gnomic sentence in the looping story. Ain’t that the truth.

Emily LaBarge is a Canadian writer based in London. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, the London Review of Books, the New York Times, frieze, and the Paris Review, among other publications. Her first book, Dog Days, was published in the UK in 2025 by Peninsula Press, and is forthcoming in the US and Canada, with Transit and Hamish Hamilton, in May 2026.