Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

The Whitechapel Gallery hosts a retrospective of the artist’s vertiginous, anarchic work.

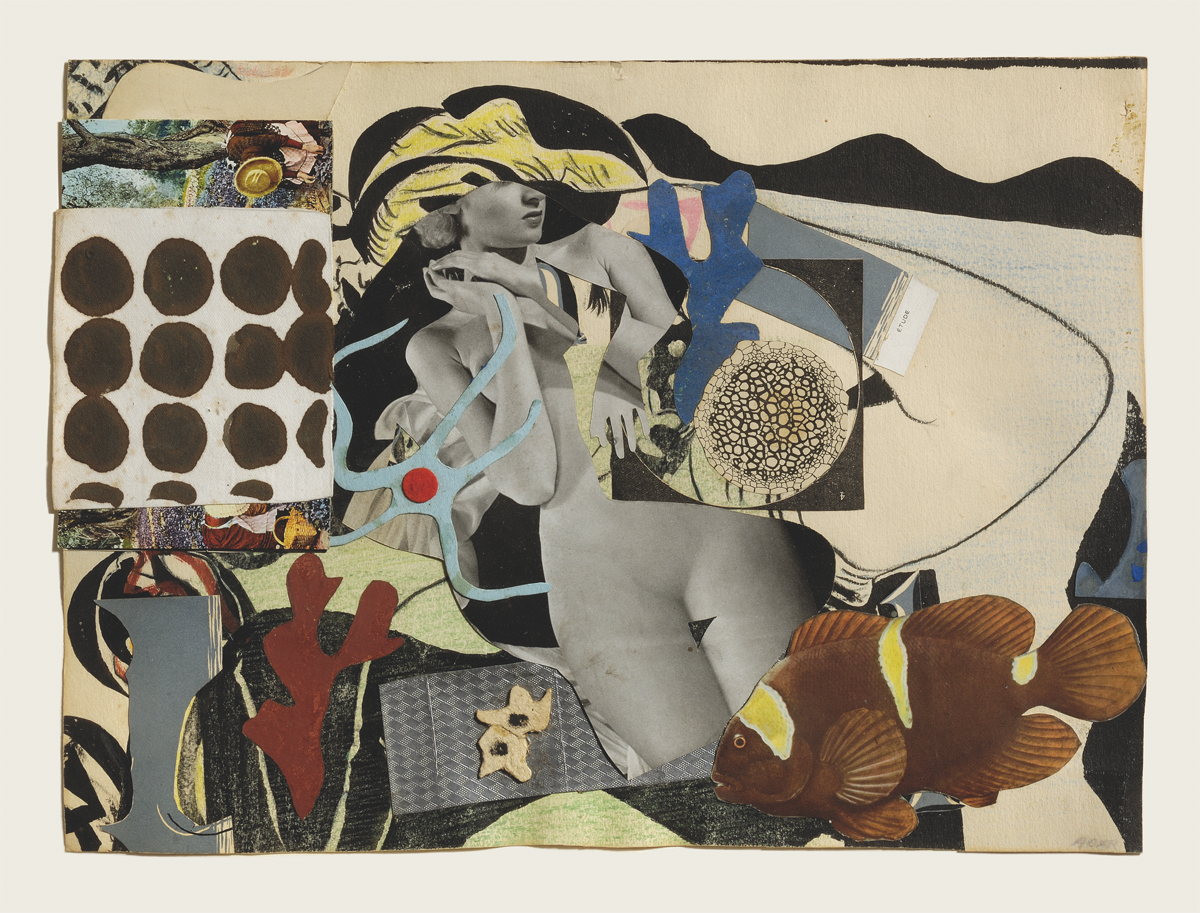

Eileen Agar, Erotic Landscape, 1942. Collage on paper, 10 × 12 inches. © Estate of Eileen Agar / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Pallant House Gallery. Photo: © Doug Atfield.

Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, Whitechapel Gallery, 77-82 Whitechapel High Street, London, through August 29, 2021

• • •

“The general effect should be a luminous space crystal,” the prolific twentieth-century British artist Eileen Agar wrote on the inside cover of a notebook dated ca. 1928–80s. Another statement just beneath: “Painting is the most astounding sorceress.” Midway through, around 1958, a string of aphorisms, from the humorous to the gnomic, runs across the pages:

HATRED OF A LIGHTER WORLD LIVING

WITHOUT THE TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE.

MOVING TO ANOTHER COUNTRY IN THE

BELIEF THAT IT IS FREE OF THE FAULTS

OF THE FIRST ONE.

SAD PEOPLE ARE OCCUPIED WITH THEIR

SMALL MINDS AND SMALL WORRIES.

ONE TYPE OF MODEL OF EXCELLENCE

IN ENGLAND—MILITANT BUSINESS-MALE.

The list of ruminations continues, giving an incisive sense of Agar’s capacious, curious mind and her lifelong tendency to theorize in big, cosmic strokes, looking for the grand lesson, the mystical in the minute and vice versa. To Agar, the world around us has always something to tell, to reveal, is full of secret inner life and meaning. One must paint, she advised in her 1988 autobiography A Look at My Life, with the “outer eye and inner eye, backward and forward, inside out and upside down, sideways, as a metaphysical aeroplane might go.”

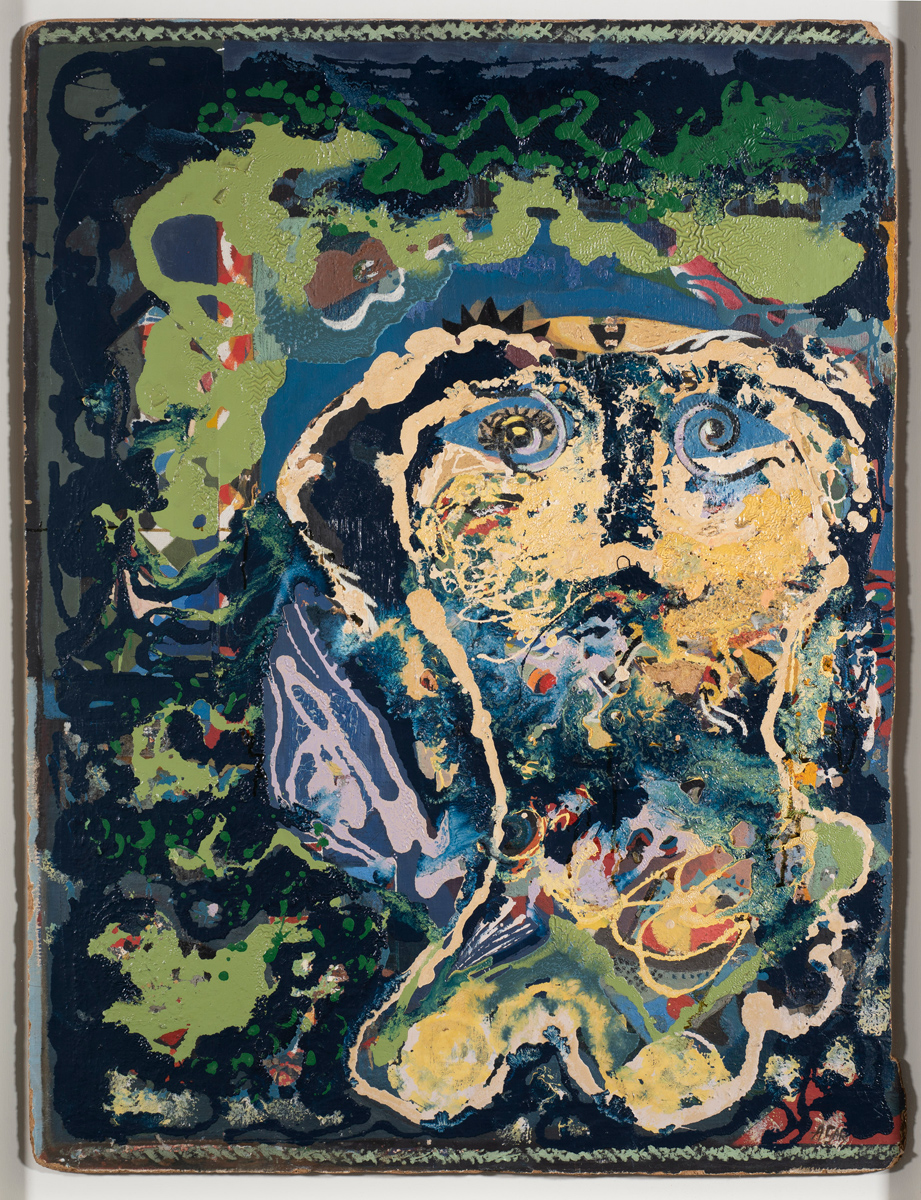

Eileen Agar, Portrait, ca. 1949. Oil on board, 35.8 × 27.8 inches. Courtesy private collection.

Angel of Anarchy at the Whitechapel Gallery is the largest Agar retrospective to date, bringing together more than one hundred paintings, sculptures, drawings, and collage pieces, including many works that have never before been exhibited. Walking through it feels like boarding that “metaphysical aeroplane,” gliding through Agar’s vast and vertiginous, colorful, energetic, heterogenous, and indeed anarchic oeuvre—restless, unusual, entirely her own—which spans much of her nearly century-long life (1899–1991). The work is varied, from early figurative portraits and experiments in Cubism to late—what shall we call it?—numinous, syncretic, large-scale, and hallucinatory paintings. Agar’s work resists neat categories, but across her varied and abundant output, motifs and preoccupations emerge in different iterations and mediums: heads, sometimes faceless, often in silhouette; bodies not quite themselves, turned angular or amorphous; women’s forms, including her own; horses; mythological figures; found objects, foliage, rocks, fossils; seashores, beaches, the ocean, vast blue expanses. The work never settles, as if its charge were to seek the next visual possibility rather than to define itself or cohere. To an extent, it also provides a record of the many movements, political and cultural, through which Agar lived and worked.

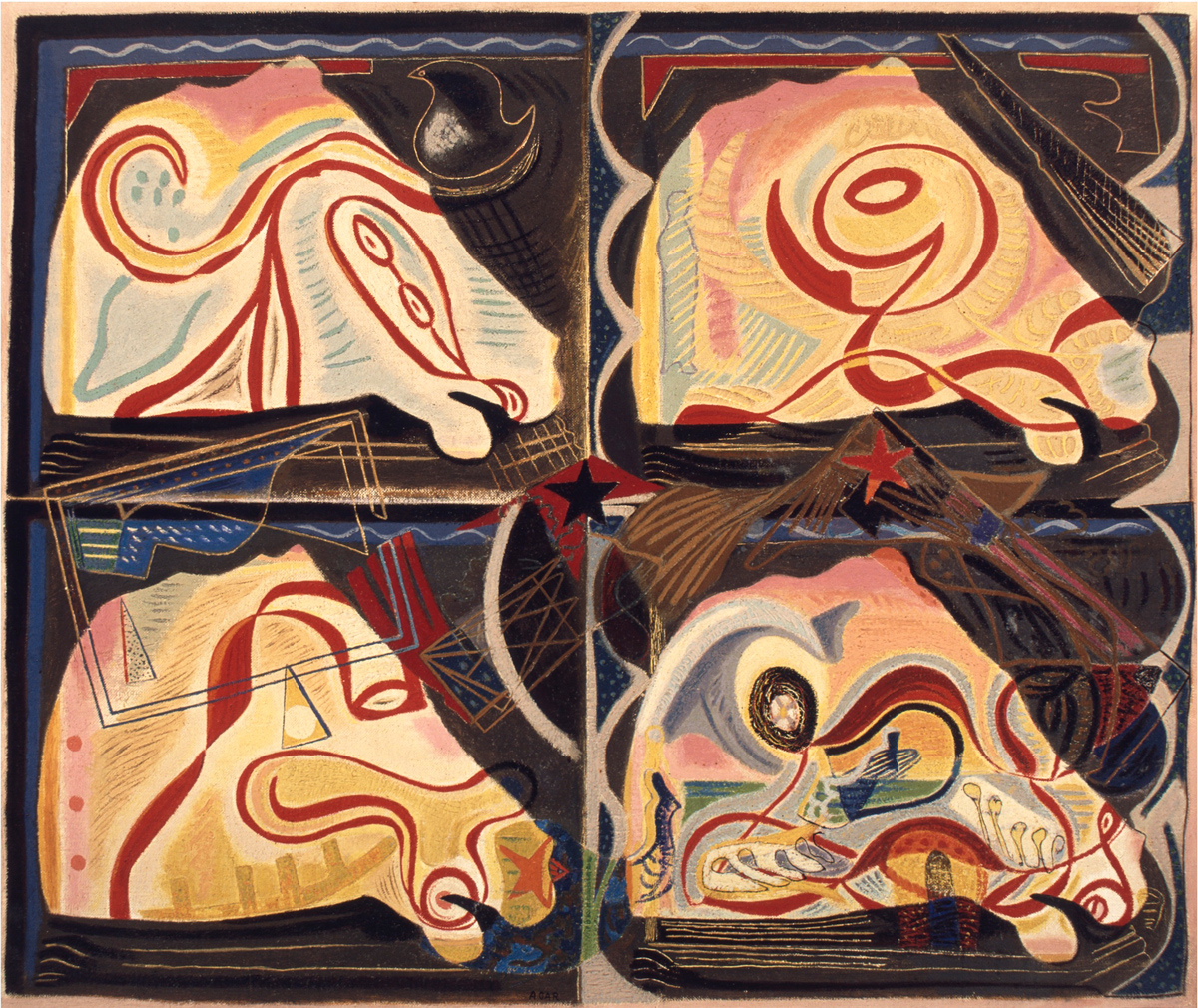

Eileen Agar, Quadriga, 1935. Oil on canvas, 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy the Penrose Collection. © Estate of Eileen Agar / Bridgeman Images.

Born in Buenos Aires to wealthy parents—a Scottish industrialist father and an American biscuit-firm heiress mother—Agar had an eccentric and independent childhood: at age six she was sent (along with a cow, allegedly, to provide daily fresh milk for the young Eileen) to England, to a succession of private and finishing schools, including one at which she was taught by the well-known English horse painter Lucy Kemp-Welch, who told Agar she must “always have something to do with art.” This confirmed matters for the young creative, who had no wish to enter the conservative and gender-conforming society circles her family favored. Next, it was a series of art schools in London, ending with the Slade, where Agar ignored the Rolls-Royce her parents sent to pick her up at the close of each day. When she finished her tutelage, Agar absconded to Cornwall, where she burned all her existing work and shaved her head, “to celebrate my new freedom!” In 1928, she traveled to Paris, where she met Brancusi, took painting lessons with the Czech Cubist František Foltýn, and encountered Surrealism via André Breton and Paul Éluard.

Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, installation view. Pictured: Eileen Agar, Three Symbols, 1930. Oil on canvas, 43.3 × 25.6 inches. Photo: Emily LaBarge.

Agar’s paintings from this period join Expressionist, Cubist, and Surrealist tendencies in form, style, and technique, producing tense and peculiar compositions. The Chagall-esque Three Symbols (1930) shows a fragment of a brightly colored Greco-Roman pillar flying through a sky of blue alongside pink shapes, an abstracted airplane, and Notre-Dame Cathedral, all of which hover above a distinctly earthbound and realistically painted Gustave Eiffel bridge. The Autobiography of an Embryo (1933–34), a large and complicated oil-on-board work, is a riotous series of images and symbols housed in overlapping geometric shapes across four distinct sections—a fusion of associative, arcane, and Surrealist content with Cubist balance and proportion: here, a wheel of colors, a naked figure with a shell for a head, a crab, a black-and-white bannerfish; there, an Etruscan sculpture, a hook-beaked white bird, pieces of coral, the palm of a hand; and everywhere, silhouetted torsos in profile and peanut-shaped forms with one radiating eye. Are these the chaotic and fecund origins of life? Or perhaps a nod to Agar’s concept of “womb-magic,” which she outlined in a 1931 issue of the literary journal The Island? “Womb-magic,” Agar speculated, is an energetic “feminine type of imagination” in opposition to the “rampant and hysterical militarism” of the masculine order she felt was so dominant in the climate of Europe in the 1930s.

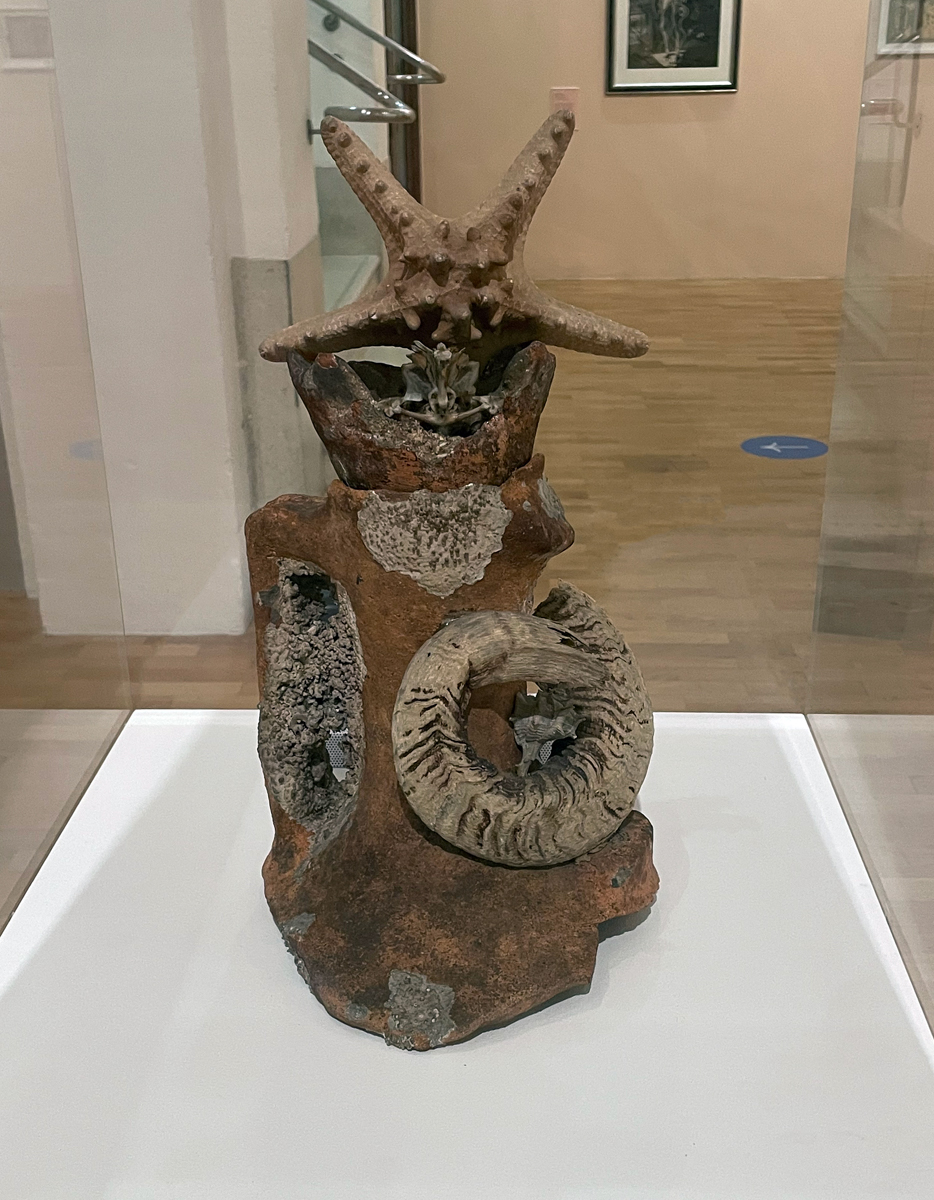

Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, installation view. Pictured: Eileen Agar, Marine Object, 1939. Terra-cotta, horn, bone, shells, 16.5 × 13.4 × 9 inches. Photo: Emily LaBarge.

Agar was one of a handful of women included in Britain’s first International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, which vocally positioned itself as pacifist and anti-fascist. Around this time, the artist played with a range of Surrealist-associated techniques—automatism, frottage, decalcomania—but was careful to keep a studied distance, particularly with regards to the movement’s views on gender, sexuality, and dream interpretation, which she perceived as overtly macho. Agar was drawn to specimens and images of the natural world rather than found manmade objects. Dozens of assemblages demonstrate her proficient belief that “collage is the mother of mobility,” allowing for transformation and openness, for both artist and audience, through unusual juxtapositions. Untitled (Box) (1935) gathers colorful specimens of coral, metal netting, feathers, fur, a blue Eye of Horus, and a perfectly preserved seahorse against a painted background in its enclosed wooden space. Marine Object (1939) adds to a flotsam terra-cotta amphora a ram’s horn, a dried starfish, a crucifix fish skeleton, and other sea encrustations to form a kind of alien bust emerged from the watery depths.

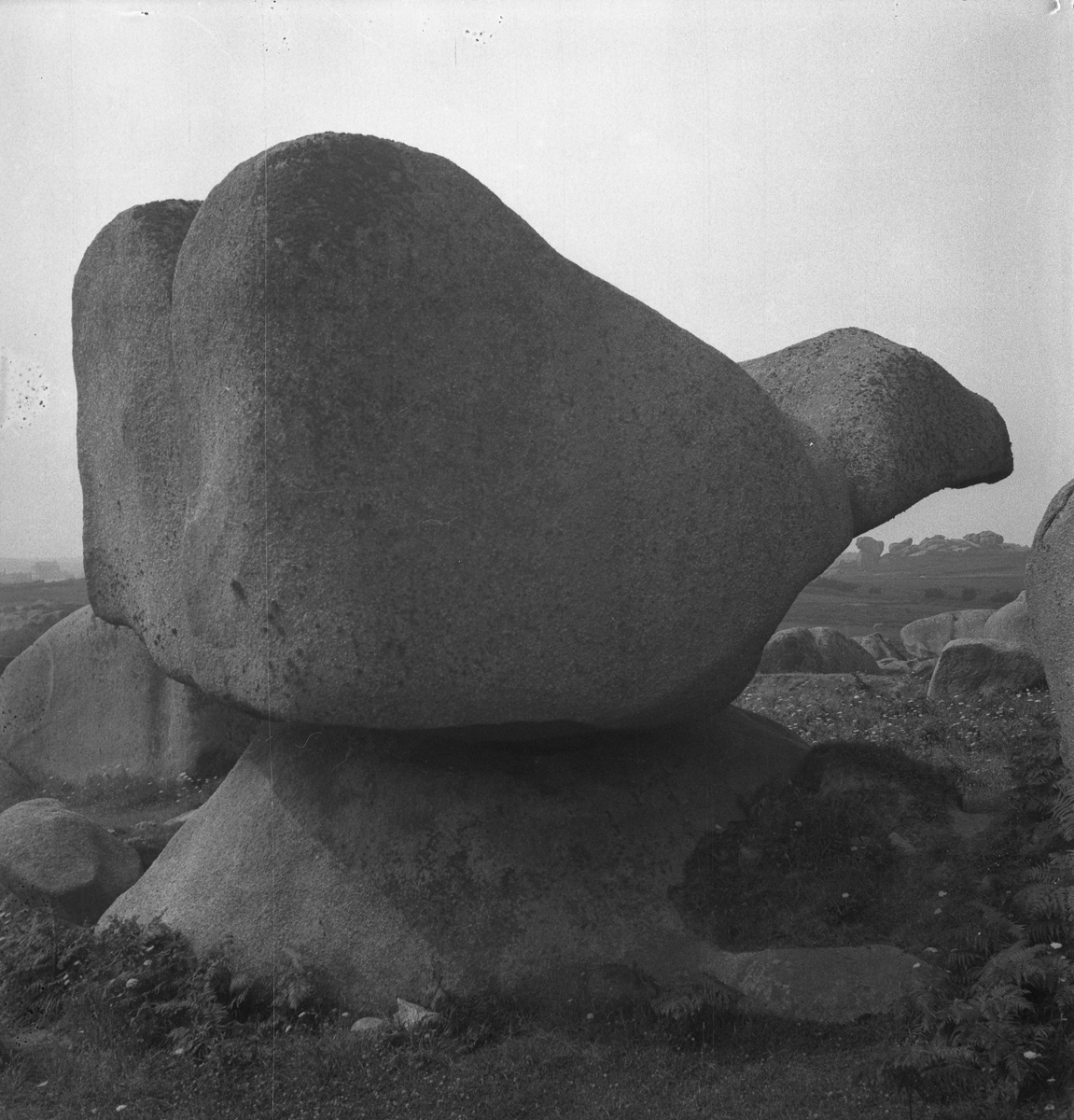

Eileen Agar, Photograph of ‘Bum and thumb rock’ in Ploumanac’h, 1936. Black-and-white negative, 6.4 × 4.6 inches. © Tate Images.

In her catalog essay, Marina Warner hypothesizes that Agar—who spent much time observing the “embedded beauty” of the fossils in Paris’s Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle—may have known of the writer and collector Roger Caillois, who wrote of nature as revealing “the existence of an underlying imaginary that is part of the real.” A room of stunning square-format black-and-white photographs (all 1936) of rocks in Ploumanac’h, Brittany, captures the keen weirdness of Agar’s eye: framed by her newly purchased Rolleiflex, the rocks appear hulking, humanoid, prehistoric. A face, a thumb, a pair of buttocks, a pelvic bone—whatever you want to see, it’s there.

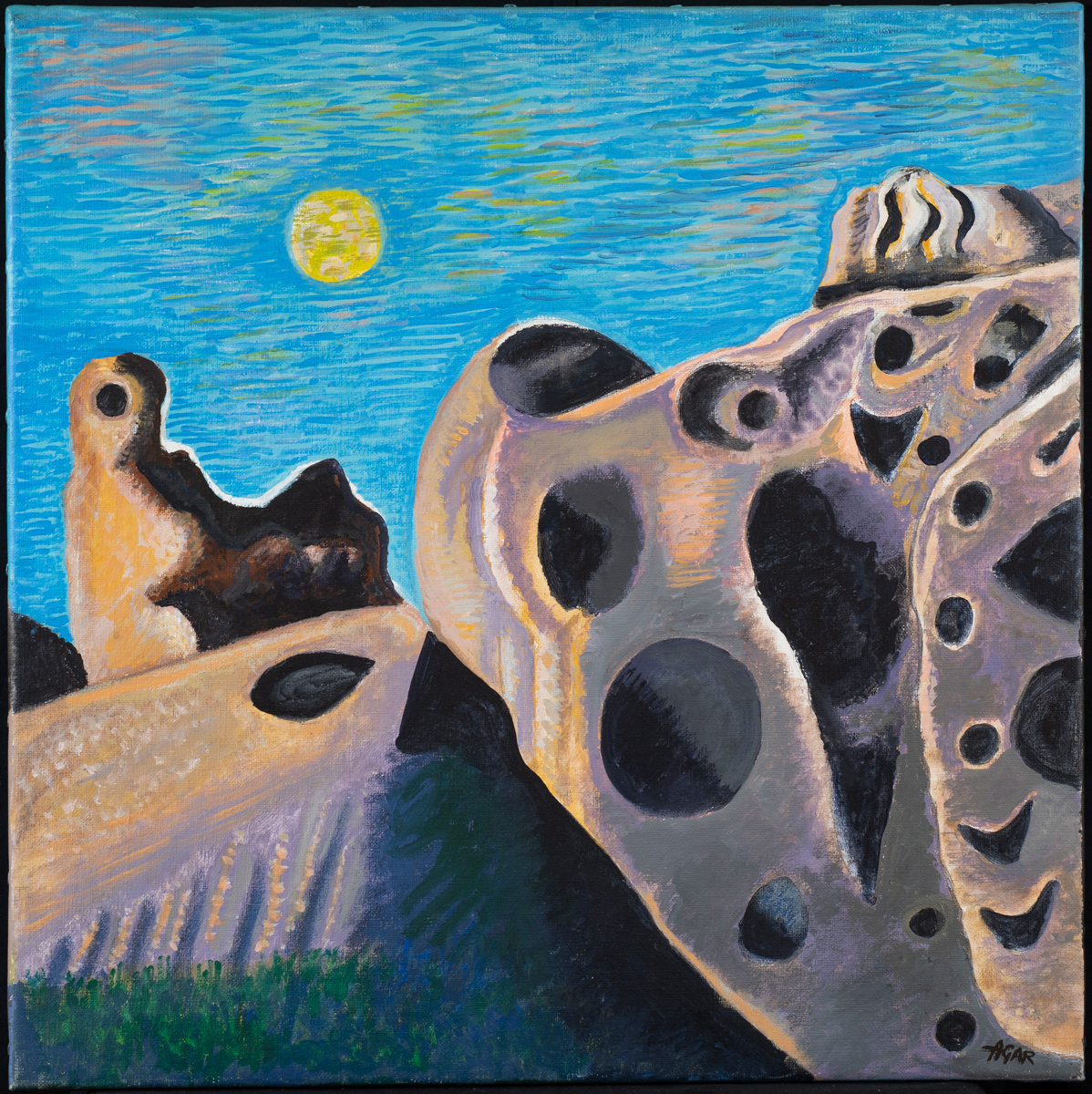

Eileen Agar, Rock 3, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 23.6 x 23.6 inches. Courtesy Redfern Gallery. © Estate of Eileen Agar / Bridgeman Images.

Agar struggled to return to art-making postwar, overcome with despondency and a floating sense of dread. Thankfully, the spell broke eventually, and her later works continued to explore ideas of the shared imaginary and the importance of a sense of play: “to play is to yield oneself to a kind of magic . . . to enter a world where different laws apply, to be free, unfettered and divine,” she asserts in one of her notebooks. Collective Unconscious (1977–78) is a vibrant patchwork of patterns, shapes, and symbols that seem to shift and move before the eye, at once in conflict and concert, a kind of painted collage. The most surprising late works, however, are the 1985 return of the artist’s eerie Ploumanac’h photographs as a series of eleven paintings that, in all admiring sincerity, look as if they were created on hallucinogens. “Surely room must always be made for joy in this world,” Agar writes confidently toward the end of her autobiography. And, on the inside cover of yet another notebook:

Life isn’t good

it’s Excellent.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London, where she teaches at the Royal College of Art. She has written for Artforum, Bookforum, frieze, the White Review, Granta, and the Paris Review, among other publications. She is the London correspondent for the Montreal-based quarterly esse arts + opinions.