Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

Dream spaces, blurred faces: a comparative exhibition illuminates the overlap in the portraiture of the two photographers.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London. Photo: David Parry.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, curated by Magdalene Keaney, National Portrait Gallery, St. Martin’s Place, London, through June 16, 2024

• • •

The two women have as much or as little in common as you want. Age, era, lifespan, education, nationality, circumstances, influences, equipment (different). First camera, duration of work, sensibility, mood, atmosphere, aesthetic, aims, desires, experiments (similar). But the oppositions and uncanny alignments between the oeuvres of the British Victorian Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–79) and the very twentieth-century American Francesca Woodman (1958–81) overlap at an intersection that I think of as the lives of girls and women. Is there a state of being more enigmatic and filled with occlusion, fantasy, and dreams, for both subject and beholder? Maybe, but maybe not (bias on my part must be conceded). Portraits to Dream In pairs the two photographers in a comparative exhibition that considers images first and biography second, arguing that each artist presented across her strange and mercurial body of work an expansive sense of photographic portraiture as a hyper unreal space—“an alternative to everyday life,” rather than a representation of it, as Woodman wrote in a Fulbright application the year before she died by suicide, aged twenty-two.

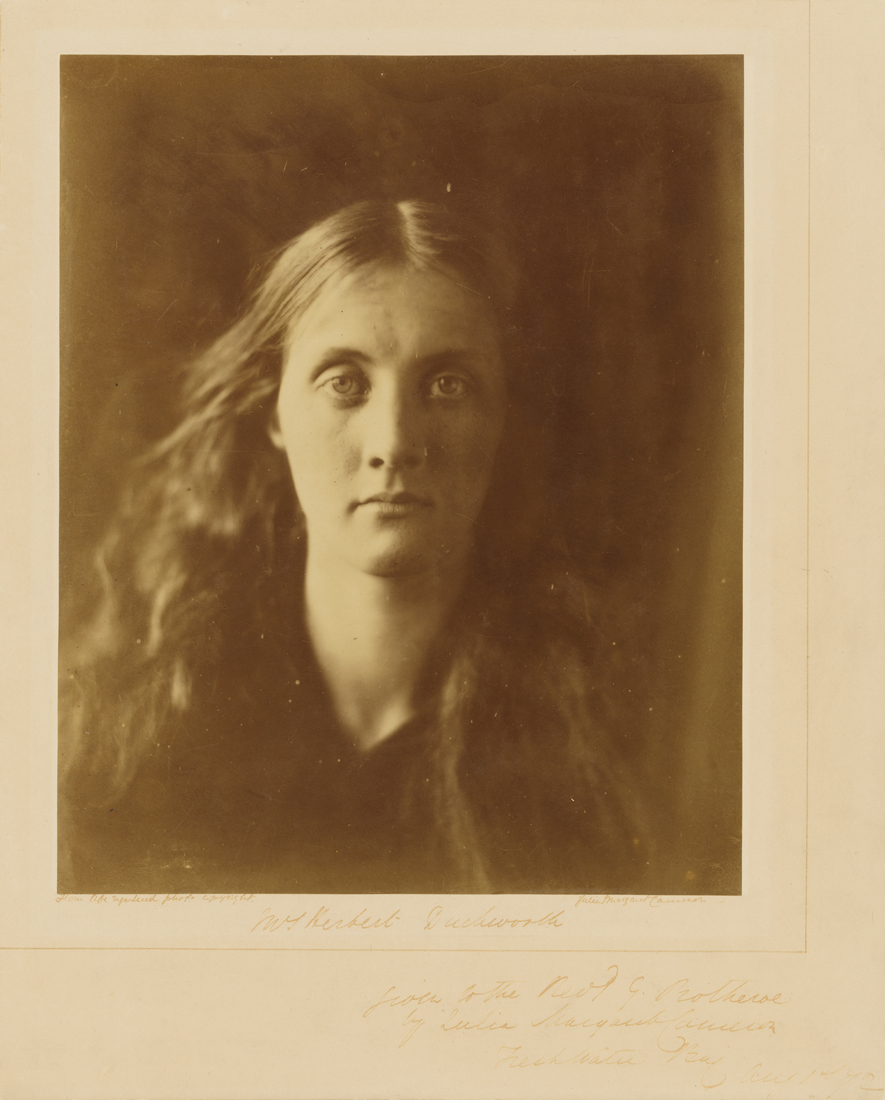

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs Herbert Duckworth (Julia Jackson), 1867. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Children and girls and young and sometimes slightly older women fill Cameron’s dusky, evocative albumen prints, which she started making at forty-eight after her daughter and son-in-law gifted her a camera. What was intended to be a divertissement became an obsession as Cameron quickly produced a large volume of portraits of friends and family, many of whom were illustrious figures: the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, the biologist Charles Darwin, the astronomer John Frederick William Herschel, her niece Julia Jackson—a favorite model of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood painters and, later, the mother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. At the same time, in her glazed “fowl house” turned studio at the end of the garden, Cameron assembled neighboring women and domestic servants in elaborate tableaux vivants to be preserved in the smudged light and soft focus of her sliding-box camera. An erstwhile coal house served as her darkroom.

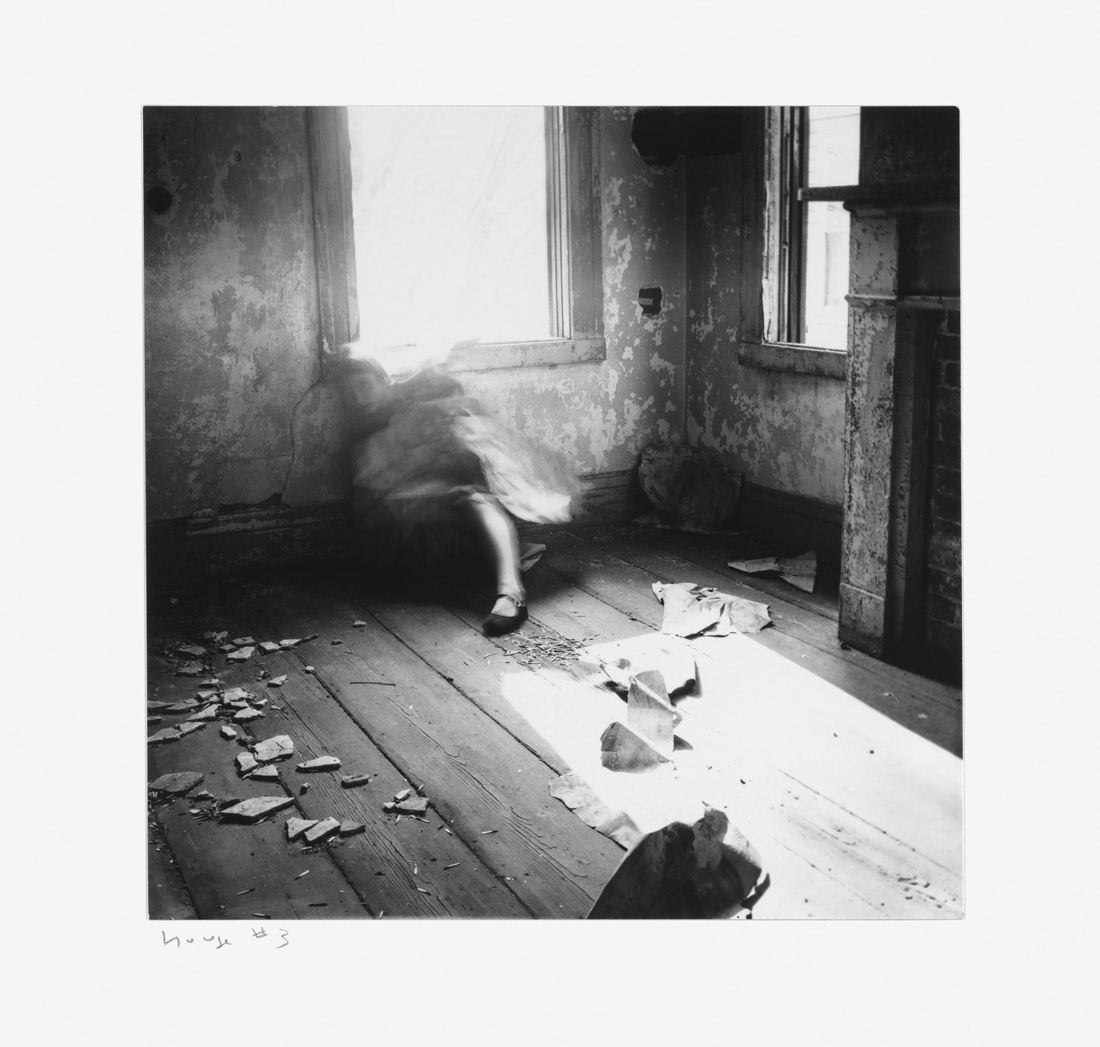

Francesca Woodman, House #3, 1976. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation. © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS.

Woodman’s black-and-white, square-format work, much of it made as a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, predominantly features her own form—nude, clothed, running through rooms, woods, graveyards, blurred in corners and doorways and windows, concealed by peeling wallpaper, white sheets, sticks, hay, grass, sloughed birch bark. Where Cameron freezes her girls and women in photographic time as archetypes (“Il Penseroso,” “The Adversary,” “The Sisters”); saints (Mary Madonna, Saint Agnes); storied protagonists, tragic and heroic (Sappho, Daphne, the Cumaean Sibyl, Elaine of Astolat, Vivien of Merlin-destroying fame), Woodman is herself in a perpetual state of becoming—dissolving and reappearing, twisting and contorting, sometimes flying, in photographic space.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London. Photo: David Parry.

Curatorial couplings are thematic—dreams, mythology, doubling, nature, muses, among others—and sometimes a little forced or literal (a photograph by each with polka dots, an umbrella, folded hands, a tree). This falls away as the exhibition progresses, and the emphasis on artistry over photographic history (so often the principal emphasis of Cameron retrospectives) brings method, technique, and experiment to the fore as preoccupations equal to subject matter. In the earliest images by both women, a play between blur and focus, shadow and raking light, dominates—whether by purpose or accident or a happy mix of the two.

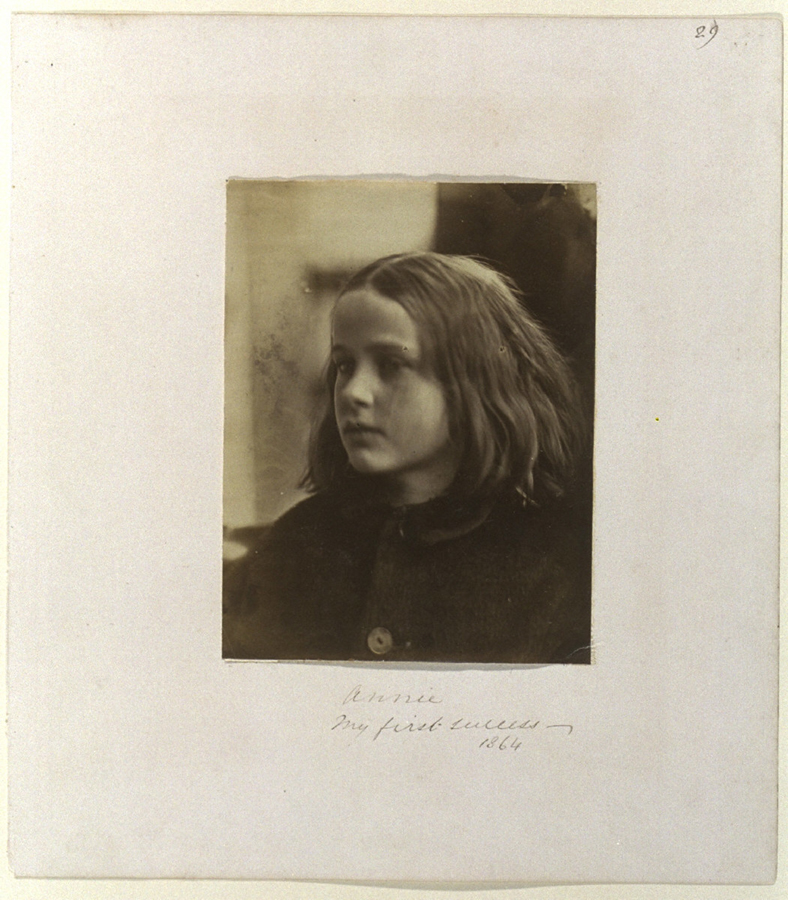

Julia Margaret Cameron, Annie, My First Success, 1864. © National Science & Media Museum / Science & Society Picture Library.

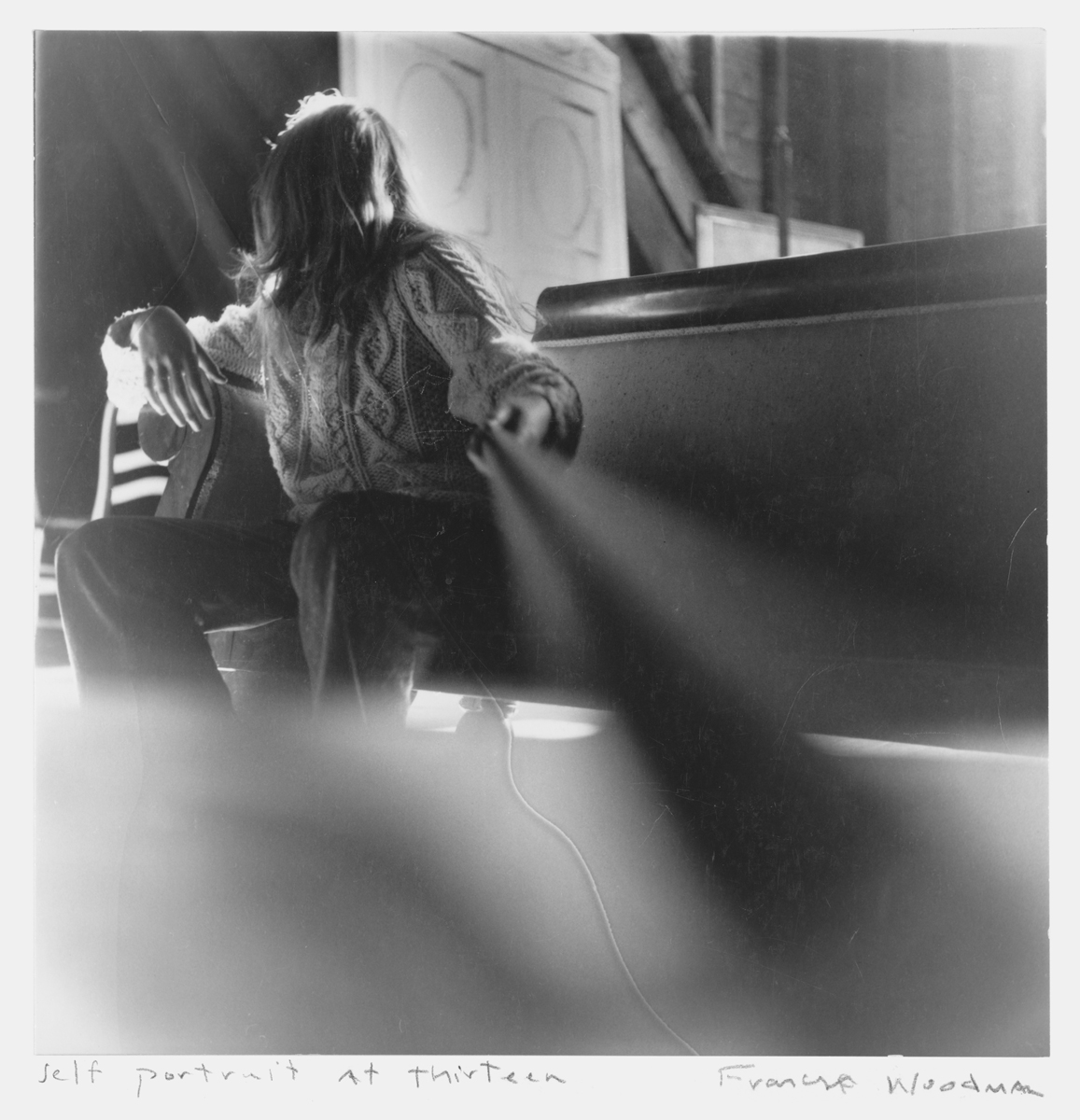

Cameron’s Annie, My First Success (1864) shows the nine-year-old girl in three-quarter profile, her shoulder-length hair unkempt and her pale eyes looking into the distance. Nothing is in focus but the curve of her right cheek, a few strands of hair, and the second fastened button of her Peter Pan–collared jacket. Everything else is blurred, the background is distorted—either by light and shade, or during the printing process—and Annie’s face is like the mirage of a girl, soft and pretty, coming and going, as if youthful hope and trepidation has seeped into the sepia-toned albumen surface. While Cameron detailed the production of her first print with pride, Woodman anointed hers retrospectively: Self-portrait at Thirteen (ca. 1972) was taken on adolescent holiday in Antella, Italy, where Woodman’s family (both parents artists) had a summer home. It was years later at RISD that she developed and named the photograph her first-ever work. The silver gelatin print captures the young photographer sitting at the end of a wooden bench, looking away over her shoulder, face obscured by wavy locks. The foreground is a giant blur, overtaken by the shutter-release cord that she pulls toward herself in a sharp diagonal. There is a shocking sense that our eye is attached to this string, is itself a camera, is being pulled out of our skull into the sfumato interior space we behold.

Francesca Woodman, Self-portrait at Thirteen, ca. 1972. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation. © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS.

“When focusing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful,” Cameron writes in her unpublished autobiography, Annals of My Glass House, “I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.” Blur as truth, blur as beauty, blur as—even—precision. In Il Penseroso (1865), Marie Spartali (1870), and Ella Norman (1872), I was transfixed by the quality of soft light and haze that settles on the faces of Cameron’s women like what I can only, somewhat mawkishly, describe as love. Their eyes and cheeks blur as if in motion, while the rest of their bodies appear motionless, as if we can see what animates them, what they want, which can never be fixed in place.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London. Photo: David Parry.

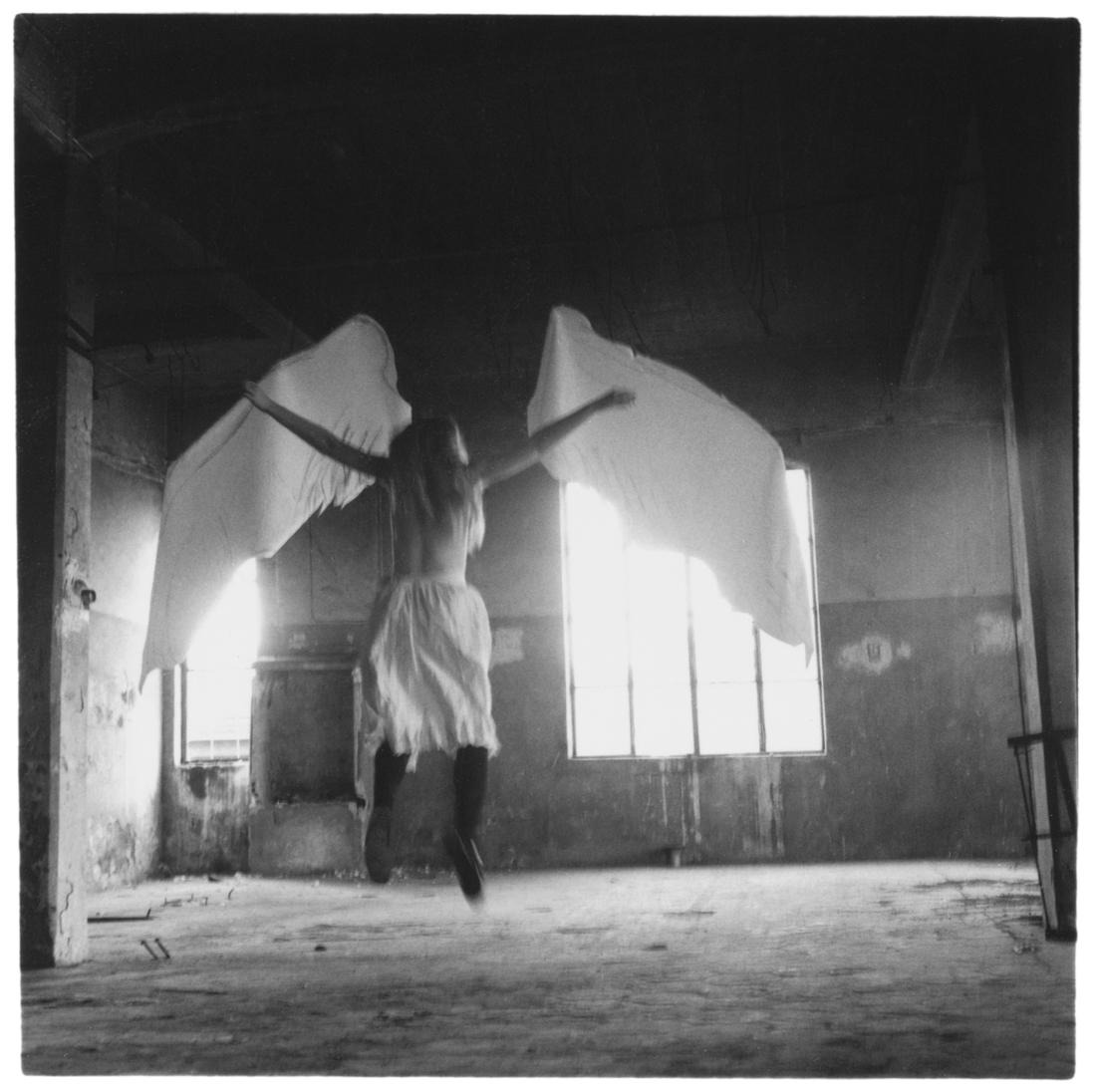

A section titled “Angels and Otherworldly Beings” hangs works by both photographers salon-style, and includes some of Woodman’s most bewitching images. Although she rarely named her pictures, several have written below them in pen, “Angels,” “From a series on Angels,” and “On being an angel.” Made in Providence as well as in Rome, where she studied abroad for a year and found influence in the Surrealist-specialty Libreria Maldoror, these show her in a rough empty room—sometimes nude, sometimes clothed, sometimes flanked by giant white paper wings suspended from the ceiling. In certain pictures, we really don’t know what we’re looking at, as light directed toward the camera lens blackens everything in its wake but a glinting, gauzy shape like, yes, an ecstatic spirit.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, from the “Angels” series, 1977. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation. © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS.

Rosalind Krauss has noted the students at RISD were often given Bauhaus school–style “problem sets” to prompt their work. What might Woodman’s problems have been? How to photograph something invisible? How to transcend gravity? How to leave your body? How to leave the earth? Many of her highly constructed pictorial answers, with their unknown questions, distort expectations of photography to embrace forced perspective, imprecision, high contrast, and movement over stillness. In 1868, an exhibition review in Photographic News described Cameron’s prints as the height of contemptuous impropriety: “wilfully imperfect” and “altogether repulsive.” A later biographer observed how she happily made prints from glass negatives that were cracked or ruined. Like Woodman, Cameron’s photographic claim was never to verisimilitude. Like Cameron, Woodman wanted to show something that could only be seen in photographs. Dreams as real as unreal.

Emily LaBarge is a Canadian writer based in London. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, the London Review of Books, the New York Times, frieze, and the Paris Review, among other publications. Dog Days will be published in the UK by Peninsula Press in 2025. Excerpts appeared in the winter 2023 issue of Granta and the autumn 2023 issue of Mousse.