Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

Impossible, endless, invisible work: three decades of the late artist’s multimedia projects.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer. Photo: Dan Weill.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, Spike Island, 133 Cumberland Road, Bristol, United Kingdom, through January 15, 2023

• • •

The work is fugitive and fleeting, but solid and voluminous. It is substantial but pliable, it is complete but not whole. The work exists across dimensions, two and three, the limitations of which are tested and embraced, collapsed, confused. The content of the work is sometimes time and space, history and memory, love and loss, vast forces that shape lives but can only be examined by their effects, some of which we might call ravages. Over time, the work disappears, fades, transubstantiates. Or the work was never there in the first place. Or you didn’t see it, because almost nobody did. Or the work is invisible. Or it is only an idea, a document, a sketch, a poster, a photograph, a list of materials. Or it was never supposed to be made. The work is impossible, it is ongoing, it is a dream, a ghost, a shadow, an impression. The work is a life, a question, perhaps—how to live?—that no one knows how to answer.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer. Photo: Dan Weill. Pictured, right: The Catherines, 1973.

“I loved the evanescence of her work,” said the poet Bernadette Mayer of her older sister Rosemary—artist, writer, educator—who died in 2014, aged seventy-one. “Beware of all definitions,” Rosemary often wrote: in her journals, on loose sheets of paper, on photographs of her early fabric compositions. Her oeuvre, produced at the intersection of varied cultural and sociopolitical “isms,” thrives on contradiction and a fruitful, delicately balanced betweenness. Mayer was as familiar with Post-Minimalism as she was Mannerism, experimental poetry as classical literature, writing as drawing. Her art is, among other things, an extended treatment in how forms repeat through eras and materials—fabric, stone, wood, paper, ribbons, snow, wind. “Forms overlaid to look like everything, be thick with everything,” she wrote on August 16, 1973, alongside some evanescent imperatives: “surfaces w.o. substance—transparent—(like angels)”; and “want work to be incomprehensible—beautiful—colors nobody ever saw before—(like holy cards).”

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer. Photo: Dan Weill. Pictured, left on back wall: Untitled (Satin and Paint), 1970.

Ways of Attaching spans three decades of Mayer’s supple and sui generis multimedia practice. Untitled (Satin and Paint) (1970), the earliest fabric piece in the exhibition, is the only surviving example of a series that challenged the two-dimensional and wall-based nature of paintings. Here, instead of raw, stretched canvas, we have a rectangular swath of golden satin edged and demarcated into three sections by long, ochre-threaded stitches. Fixed directly to the wall, it sags loosely, crumpled and gathered where it was roughly smeared with eddies of white paint that pull convulsively at the rich sheen of the fabric.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer. Photo: Dan Weill. Pictured, left: Galla Placidia, 1973. Satin, rayon, nylon, cheesecloth, nylon netting, ribbon, dyes, wood, acrylic paint.

Other fabric works, made in 1973, marry the artist’s interest in disrupting space and display conventions with her emergent politics—the product of a feminist consciousness-raising group as well as cooperative organizing. (Mayer was one of the cofounders of A.I.R. gallery, the first nonprofit artist-directed gallery for women artists in the United States.) The Catherines is a vision in gold, rust, brown, taupe, mustard, green, and purple: overlapping veils hang in long swags, like errant drapery, from a sequence of curved wooden rods that extend from a central pole, so that the work appears a rippling, ovoid vortex. An exercise in collective nomenclature as historical preservation, the work honors, Mayer said, all the great Catherines of history. The extraordinary and sumptuous Galla Placidia refers to the fifth-century regent of the Western Roman Empire. Purple, gold, olive, pink, emerald, lime green, the sheets of satin, rayon, cheesecloth, and nylon netting hang from a wooden hoop bisected by two rods that collect the colors so they droop down softly in rounded layers and folds—different at each circumlocution of the sculpture, each ray of light shining through, each subtle gust of air.

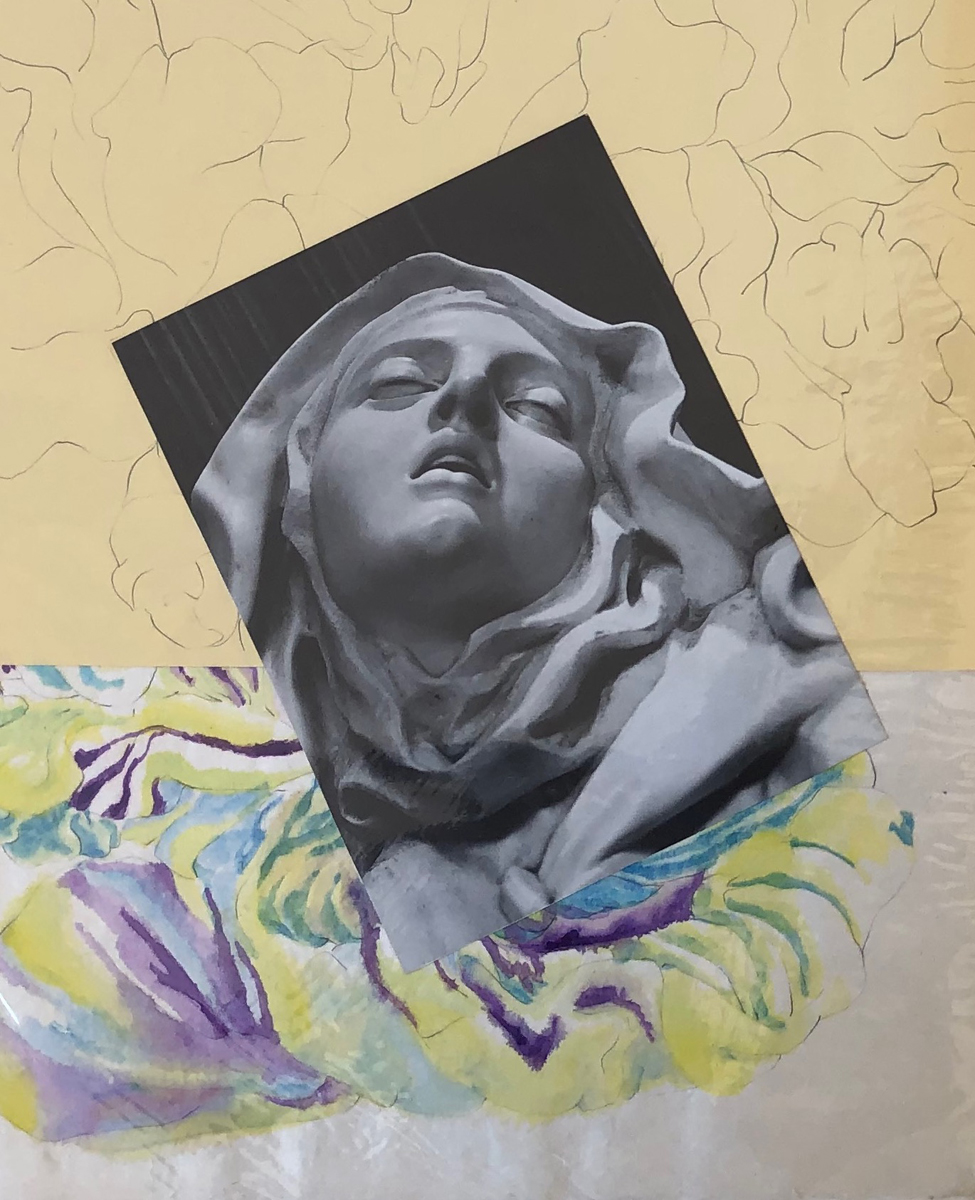

Rosemary Mayer, Passages, 1976 (detail). Collaged pages in plastic sleeves, handmade binding and red velvet cover. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

These flowing shapes and colors repeat in drawings and sketches of the same period, as well as later, when they morph into discernable objects, like flowers, ribbons, tents, elegant scripting of names and dates. They can be glimpsed in Mayer’s intricate handmade artist’s book, Passages (1976), a document of her only trip to Europe, in 1975, from New York, where she was born and lived her entire life. In it, Jacopo Pontormo’s The Deposition from the Cross (1528) mingles with Jean Fouquet’s Madonna Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim (1452), Piero della Francesca’s Battista Sforza (1465) is overlaid with meditations on dying flowers, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–52) takes center stage on several pages—her swooning face up close, surrounded by stony ripples of fabric, the angel about to pierce her heart with a spear of gold. Throughout these works on paper, including a series of drawings Mayer called “impossible”—plans for fabric sculptures that defied real-life principles and spatial logic—it is as if drapery, how it functions, even in absence of a body, is something cosmic and timeless. Forms are mirrored and multiplied, arranged and rearranged, much like Mayer’s unrealized ENDLESS WORK (1972), a piece to which new fabric would be affixed ad infinitum for the next and the next iterations.

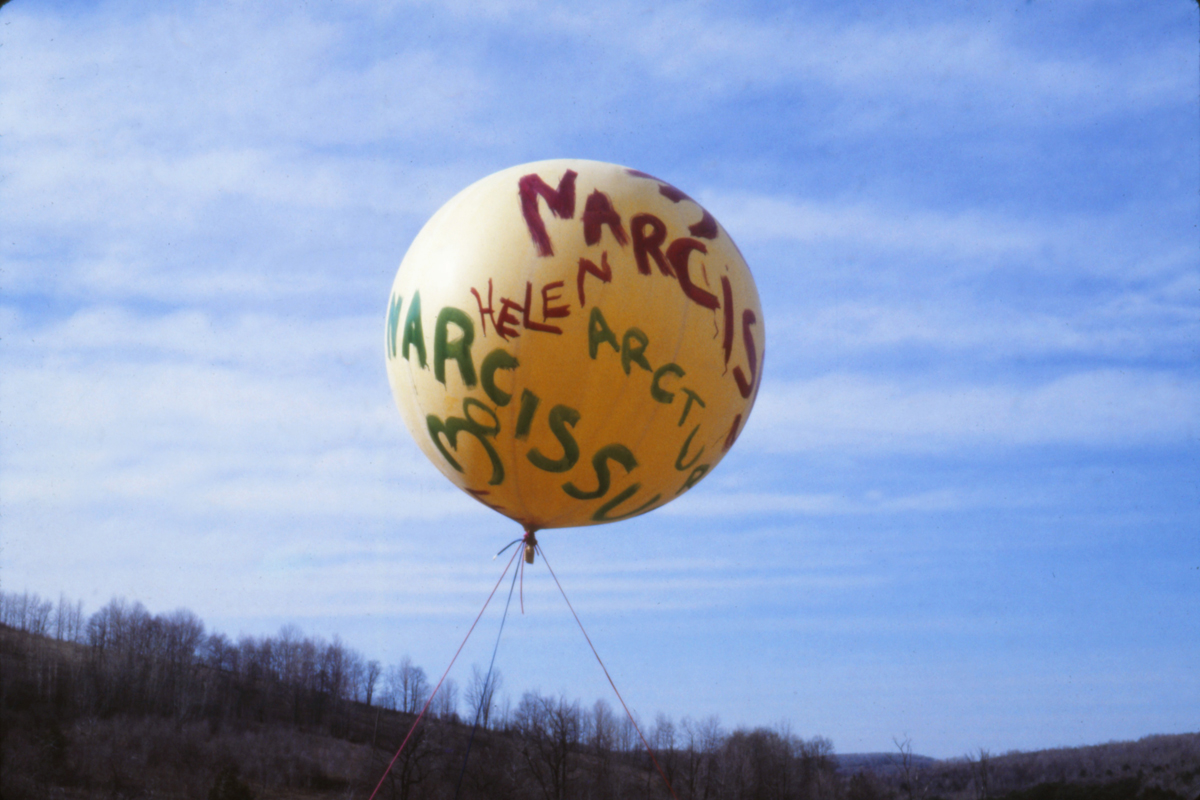

Rosemary Mayer, Some Days in April, installed during the week of April 17, 1978 (detail). Balloons, helium, paint, fabric, rope, and wooden rods. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

In the late 1970s, Mayer’s acts of memorialization continued with a series of “temporary monuments”—durational sculptures, land art, urban installations, sky poems, weather performances, it’s hard to know exactly what to call them: beware of all definitions. Spell (1977) and Some Days in April (1978) both involved writing text on weather balloons tethered to the ground by strings and ribbons—flower names to usher in spring in the former (“Iris Return,” “Crocus Return,” “Hyacinth Return”), and the names of spring flowers, constellations, and lost family members and friends in the latter. While Spell was plagued by whipping winds that tore the balloons from their fixings on a building roof, Some Days in April seems to have been placid, though its presentation took place on private land and had no audience. Photographs show the bright orbs floating against dark hills, tied to the ground with gentle curls of yellow, purple, and red. We see the name Ree, for Ree Morton, a close friend of Mayer’s who had died recently in a car accident, and Marie and Theodore, for Mayer’s parents, who died when she was a teenager.

Rosemary Mayer, Some Days in April, installed during the week of April 17, 1978. Balloons, helium, paint, fabric, rope, and wooden rods. Courtesy the Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

My heart stuck in my throat looking at both of these pieces. Who doesn’t know what it’s like to wish for the return return return of something that never will. Yet the invocation brings something else vital into being, albeit in a different incarnation. This is enough, or has to be. These “temporary monuments” telescope from the micro to the macro, the individual to the universal, the grounded to the celestial—they are experiments in ways of attaching, as in knotting together and binding, holding fast to the earth, in hand or heart, balanced just so, if for a moment only. How to memorialize life—a particular life, life in general—all of it? Every Catherine, every ancient matriarch, every parent, friend, lover, sister, high spring wind, melting snow, dying bloom? How to give each form substance and value, even when it is insubstantial, fleeting, ruined, obscure? How to make life radiant, as it is; to make it bearable, as it is sometimes not? This body of work, as Mayer described it, is somewhere “between sculpture and celebration, decoration and private magic.” A life’s work—the work of art—it is endless.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London. She has written for Artforum, Bookforum, the London Review of Books, and the Paris Review, among other publications. Dog Days, a work of nonfiction about trauma and narrative, will be published by Peninsula Press in 2024. An excerpt is forthcoming in the Winter 2023 issue of Granta.