Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

The beautiful, anti-bourgeois, language-breaking works of the

twentieth-century Belgian artist.

Sophie Podolski: Wisdom Should be Sung, installation view. Courtesy Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art.

Sophie Podolski: Wisdom Should be Sung, Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, St James’, New Cross, London,

through August 24, 2025

• • •

“If I were the mayor of Ixelles, well I’d be the mayor of Ixelles,” Sophie Podolski says, in her gravelly, singsong voice, joking but also not. “And I’d plant cabbages in the spring park of my communal house where I live and I’d hand out free cabbage. And everyone would eat cabbage and fart all the time.” The camera scans across a crowded kitchen, fridge and furniture in ad hoc arrangements, piles of empty bottles, a pan abandoned on the stovetop, cupboard doors and drawers half-open, and then out into the scrubby back garden, overgrown with giant hostas, hydrangeas, weeds. “I’d have a farting commune, you understand? But I’d have the best farting commune of all, and I’d be a good mayor, and everyone would have a good intestine, very, very strong.”

Sophie Podolski: Wisdom Should be Sung, installation view. Courtesy Goldsmiths CCA. Photo: Rob Harris. Pictured, center right, on brick wall: Joëlle de La Casinière, Dans la maison (du Montfaucon Research Center), 2017.

The black-and-white footage of the artist—who was born stateless to immigrant parents in Belgium and granted citizenship there only the year before she died in 1974, aged twenty-one—comes from Joëlle de La Casinière’s 2017 archival 16mm film Dans la maison (du Montfaucon Research Center). Made on a summer’s day in 1973, some forty-four years before it premiered, the piece runs just over an hour and documents a communal residence in Ixelles (a Brussels municipality southeast of the city center) that hosted the five members of the titular Brussels art cooperative (including De La Casinière) from 1968 to 1973. It is dedicated to Podolski, who flickers in and out of the frame in still and moving images, her voice lilting in the background, speaking nonsense poetry, espousing flatulent mayoral ambitions, and hinting at the anarchic views of the group who dedicated their aesthetic program to the “overthrow of the semantic order,” in the words of another member and filmmaker, Michel Bonnemaison.

Sophie Podolski: Wisdom Should be Sung, installation view. Courtesy Goldsmiths CCA. Photo: Rob Harris.

Wisdom Should be Sung is the first UK solo exhibition of Podolski’s oeuvre, which encompasses drawings, etchings, collages, archival materials, and texts, including graphic poems and a novel, Le pay où tout est permis (1972). In the spirit of other countercultural movements of the time, Podolski and her fellow “freakies” (as the group called themselves, in opposition to “hippies”) made the house in Ixelles a kind of country of its own, in which they lived by their own rules and everything, really, was permitted. She joined Montfaucon at sixteen and was furiously productive until her death from injuries sustained during attempted suicide six years later. (Podolski was diagnosed with schizophrenia at eleven, and her illness worsened over time.) In the corner of the show, surrounded by the artist’s vast output of wild, extraordinary, utterly sui generis endeavors, Dans la maison plays on a loop, showing flashes of the rooms in which Podolski and her friends lived, experimented with drugs, made art, dreamed of finding ways to survive capitalism, war, violent governing structures, the tyranny of a coherent self.

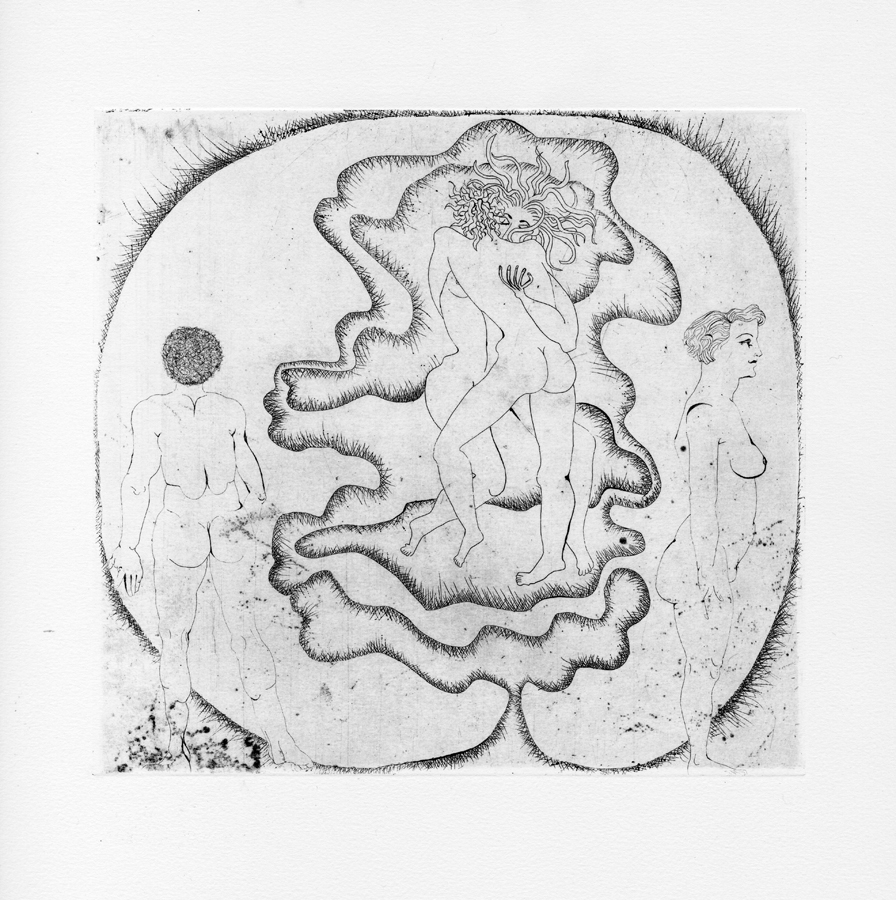

Sophie Podolski, Sans titre, 1968–69. Courtesy Château de Rochechouart, Musée d’art contemporain de la Haute-Vienne. © Catherine Podolski.

All the works are untitled, and all, save a handful from 1968 to 1970, are undated, but attributed to her time at Montfaucon. And they are fabulous, weird, scary, beautiful, funny, sad, haunting, revolutionary. Sinuous nude figures of ambiguous gender embrace in the midst of writhing clouds, an otherworldly miasma; a weathered, hollow-cheeked woman dressed like she’s on her way to a garden party, but for her long black gloves, reaches out to pluck a nude woman’s pert nipple while unidentifiably feathered creatures swirl and wheel overhead; a rotund woman sunbathes in a deck chair underneath which (what looks to me like) a massive turd steams in the sand; and a hirsute man sits cross-legged reading a newspaper whose floating headlines announce (in French, my translation here): 36 MURDERS YESTERDAY NIGHT — 3 KILLED 6 WOUNDED — BOMB ON THE ISLAND — INFANTICIDE — THE EXTERMINATION OF INDIANS.

Sophie Podolski: Wisdom Should be Sung, installation view. Courtesy Goldsmiths CCA. Photo: Rob Harris.

In other images, bodies transforming, grotesque satire, fantastical carnivalesque characters, and sometimes just body parts (by which I mean, primarily, genitalia) roam through imaginary worlds teeming with life, fellow alien creatures, hybrids, and who-knows-whats. One work shows a horse with a single hornlike eyeball, another an eyeless rat king in a toga worshipped by flanks of green armless, spermy mermen. Elsewhere, a walrus lady with black wings sucking from a gas pump that reads “BLACK BLOOD.” An army of clowns masturbate, and a flying cock and balls bursts from a jelly cake. Skies and landscapes and backgrounds and foregrounds are overtaken by dense graphic patterns and crosshatching, or remain blank, running with text spare or chaotic.

Sophie Podolski, Sans titre, Titre attribué: La table de Gérard. Courtesy Château de Rochechouart, Musée d’art contemporain de la Haute-Vienne. © Catherine Podolski.

I’M IN LOVE

LITTLE GIRL WHO

BREAKS HER HANDS

I LIKE THAT IT’S

GREAT! IT’S COMPL-

ETELY SKIT-

ZO I LIKE

THAT

That one reads like an R. D. Laing–inspired haiku. Others mix violent anti-capitalist imagery sprinkled with theory and literature: “Molière was a guy like Buster Keaton,” “Colourless green ideas . . . see jackobson,” “the slug is a (massive) snob!,” and—my personal favorite—“But will we be such gentle machines for much longer?” With her psychedelic, hallucinatory images, her aesthetic assault on bourgeois values, and her critique of language and culture as systems that require breaking, it’s easy to see why Podolski was admired and published by the French Tel Quel crew (Julia Kristeva and Philippe Sollers were fans), as well as considered alongside other experimental artists and writers like Brion Gysin and Pierre Guyotat in exhibitions and magazines. (The Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño was influenced by Podolski’s writing, which he came across in the 1977 issue of Marc Dachy’s Luna-Park magazine, to the extent that she appears as a figure in numerous of his short stories and poems.)

Sophie Podolski: Wisdom Should be Sung, installation view. Courtesy Goldsmiths CCA. Photo: Rob Harris.

One might think contextually of Laing’s anti-psychiatry movement and the art his patients made at Kingsley Hall in the mid-1960s, or Sylvère Lotringer’s legendary Schizo-Culture conference of 1975. Podolski’s visuals fly between Max Beckmann, Toyen, Shuvinai Ashoona, Jacqueline de Jong, Mary Ellen Solt, Robert Crumb, stoner drawings, jokes, doodles, the Book of Revelations. But the more I looked at Podolski’s work, the stupider it seemed to try to attach to it a lineage or a canon, even a radical one. Stupider, even, to try to describe or explain it, given its aims to doff semantic systems, to offer only rupture, not certainty, as if each image might disappear at any moment, or shift beneath the gaze, warp and twist and pull you in, if you’re lucky. I don’t know what any of it means, because, let’s face it, meaning is the problem, meaning is a trick, meaning brings us closer to the world we know and further from the world we want to imagine—somewhere less ugly than here, somewhere the self is multiple, somewhere everything is permitted. “We are never more than assistants to the void,” Podolski wrote in her novel, a deranged call to arms. This is the best, most shocking show I’ve seen this year, because I forgot what it was like to look at art invested enough in the world to stop giving a fuck about what it demands so absolutely—in art, life, whatever.

Emily LaBarge is a Canadian writer based in London. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, the London Review of Books, the New York Times, frieze, and the Paris Review, among other publications. Dog Days will be published in the UK by Peninsula Press in 2025. Excerpts appeared in the winter 2023 issue of Granta and the autumn 2023 issue of Mousse.