Jo Livingstone

Jo Livingstone

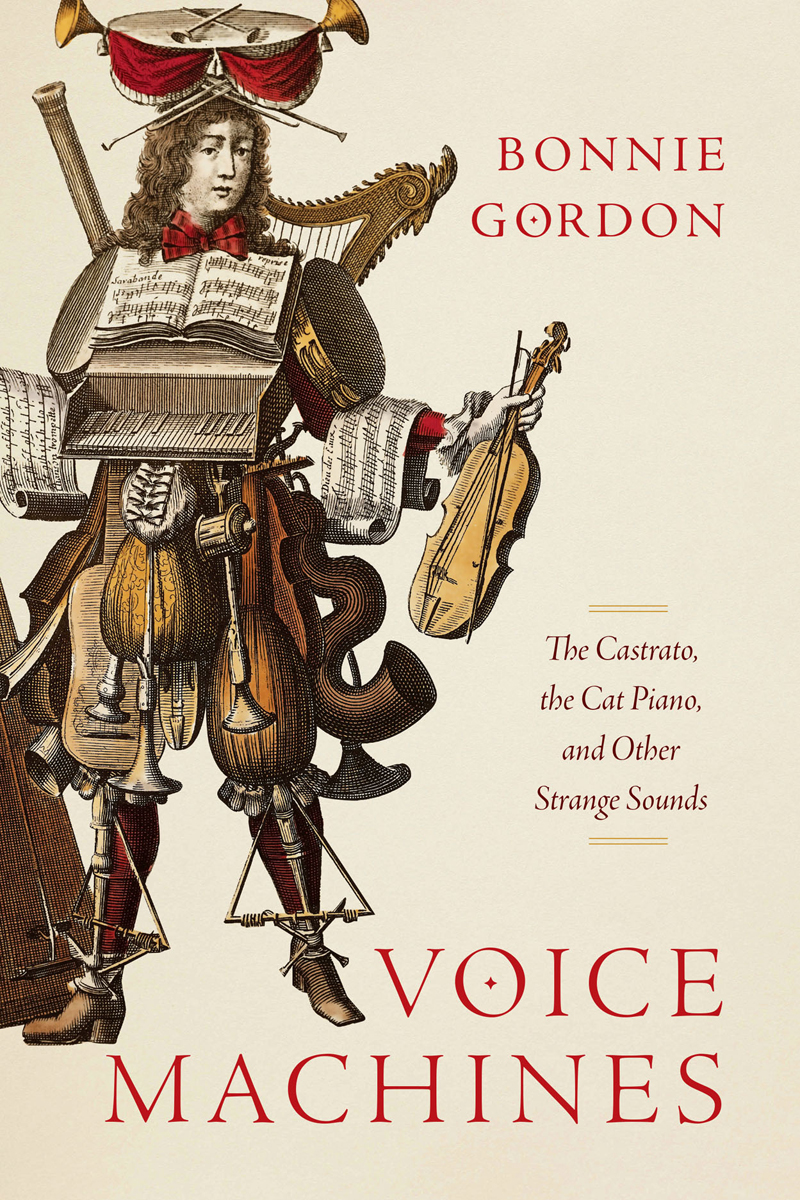

Drawing from the history of castrati singers, musicologist Bonnie Gordon explores connections between sound, voice, and the mechanization

of the physical body.

Voice Machines: The Castrato, the Cat Piano, and Other Strange Sounds, by Bonnie Gordon, University of Chicago Press, 416 pages, $55

• • •

Pietro della Valle was a musician and writer from Rome who was involved in the contemporary music scene. In a 1640 essay, he mentioned how bored he was of the melodies produced at his local place of worship. Only fine music inspired in him “feelings of devotion, of compunction, and even of a desire for the afterlife and celestial things.” One reliable source of such marvelous song? The castrati of his time, who produced wonderful sounds that drew him in. Perhaps, in this predilection, he was a “uomo troppo sensuale,” della Valle worried.

This tension between the sensuality and religiosity of song is the organizing motif of musicologist Bonnie Gordon’s new book, Voice Machines: The Castrato, the Cat Piano, and Other Strange Sounds. In Italy, castrati were recruited to perform in church and court from the late sixteenth century, taking on the parts that women would have if they were allowed to. Per the Bible’s injunction and as affirmed by Pope Sixtus V, they were not.

Taboo though the subject of castrating children might be, the idea of singing women was more taboo, Gordon tells us, for the early modern Italian church. Writers of the period theorized that the gorgia, the glottal place in the throat, was the mirror-part to the cervix, opening and closing access to the body’s organs, making a woman trilling in church deeply inappropriate. The “direct link” between the two cervical regions, Gordon writes, “turned singing into an erotic activity that compromised the reputations of even the most chaste singers.”

In present-day English, the word “organ” means a bit of the human body and also a musical instrument. This semantic overlap is not an accident, Gordon notes, like with other words that occur amphibolously throughout her study, “humor” and “genius,” which both have double meanings (bodily humors and comedy, extreme cleverness and genetic information) coined in early modern conceptual fusions. In the castrato’s era, Gordon writes, “instruments, tools, and organs never existed in a separate and autonomous sphere.” So, “organ” derives from Latin organum, meaning instrument, itself derived from Greek’s ὄργανον, meaning “tool, instrument, or organ of the body.” An organ is pliable and alive, a thing that does other things. For Aristotle, an organ could mean a plant or an animal or a philosophical system. “In modern terms,” Gordon goes on, “one might think of the notion of organ as encompassing bodies, technologies, and artifacts—like the telescope, record player, and camera—or as symbolic forms or modes of perception—such as perspective, theater, and words.”

This is how and why Gordon discusses the castrato in the language of machinery. The book’s subtitle mentions a “cat piano,” a horrid and hopefully apocryphal notion formed by kittens supposedly penned in a row and made to squeak by keyboard-connected spikes striking their tails. Gordon shows how, in the context of new Galilean telescopes, which prosthetically enhanced the human eye, and advances in hydraulic and air-powered musical organs, the cat piano and the castrato—a human musician like, say, mezzo-soprano Loreto Vittori, composer of the opera La Galatea (1639)—fall into the same category of instruments “mechanized” by technologies like surgery, training programs, and cages. (Gordon is wise to leave much of the detail of the surgeries and the traditions that formalized them to the end of the book, which will at least make readers hoping for scandalous tidbits work for their gratification.)

Gordon’s argument lifts off where she connects the language of mechanization to the backlash against the sensual provocations of the castrato voice. She cites an 1825 critique of a performance by the castrato Giovanni Battista Velluti in London Magazine and Review: “That he is a perfect master of the science it is easy to perceive,” the critic wrote. However, “the precision with which Velluti executes the most difficult passages, can only be compared with that of a piece of machinery . . . Some pieces of music he performs exactly as a steam-engine would perform them.”

Here, mechanization is repurposed as a means to dehumanize, a classic rhetorical pivot that occludes the actual problem—the eroticism of the castrato instrument. One piece of contemporaneous writing describes its seductive power. “These pipes of theirs,” Gordon quotes, “resemble that of the Nightingale; their long-winded throats draw you in a manner out of your depth and make you lose your breath.” In another famous story, Vittori abducted a noble girl he was dating, causing a scandal wherein her painter husband demanded her return. This cloud of suspicion of sexual threat is ultimately the reason the castrato left the church.

In June of 1587, Pope Sixtus V issued the papal bull Cum frequenter, which made it a violation of canon law for castrated men to wed and ordered the end of such already existing unions. Perhaps finding in these partnered castrati a nice scapegoat, Sixtus’s bull redefined marriage to be a contract between a woman and a man whose semen could conceive children; this bull is the reason that, well into the twentieth century, an infertile husband was grounds for annulment. Having introduced the castrato to the stage in order to tame men’s reactions to women, the church now found that the congregation, being inexplicably attracted to castrated men, were endangered by them, and imposed greater sanctions on everybody’s sex lives.

Gordon describes Voice Machines as the work of two decades. She plays the viola, and her previous book is Monteverdi’s Unruly Women, a study of the women who brought the composer’s madrigals and early operas to life; she also coedited The Courtesan’s Arts, a collection about the creative arts of sex workers across cultures and histories. Both titles are superb. She is associate professor at the University of Virginia and has worked in the wake of the Charlottesville violence to foster political equity, including as codirector of the college’s Sound Justice Lab.

The long years of its writing make for stunning research in slightly outdated packaging. Gordon’s style retains some quirks of academic-speak, phrases like “exemplified the ways in which.” In theoretical terms, she embeds her data in a few reliable old post-structuralist frameworks. They may not be new, but they’re the right ones: the cyborg of Donna Haraway and the organs-without-bodies of Deleuze and Guattari could have been custom-argued to help us consider the castrato.

The question of the morality of alterations to the body concerning sex and gender is once again at the forefront of right-wing political organizing. Gordon is undistracted by the transphobic explosion in contemporary politics, confining herself to the merest gestures toward the Supreme Court and other implications for the present day—she always centers the music. And yet, her argument is undeniably topical: Voice Machines insists that individual people with bodies relate and respond to the creative cultures around them, as well as to each other, ungovernably. Resisting a closure that would be false, she lets the reader hear the harmony and name it for themselves.

Jo Livingstone is a critic based in New York.