Beatrice Loayza

Beatrice Loayza

Léa Seydoux radiates charm and emotive force as a single mother grappling with life’s inconsistencies in Mia Hansen-Løve’s latest.

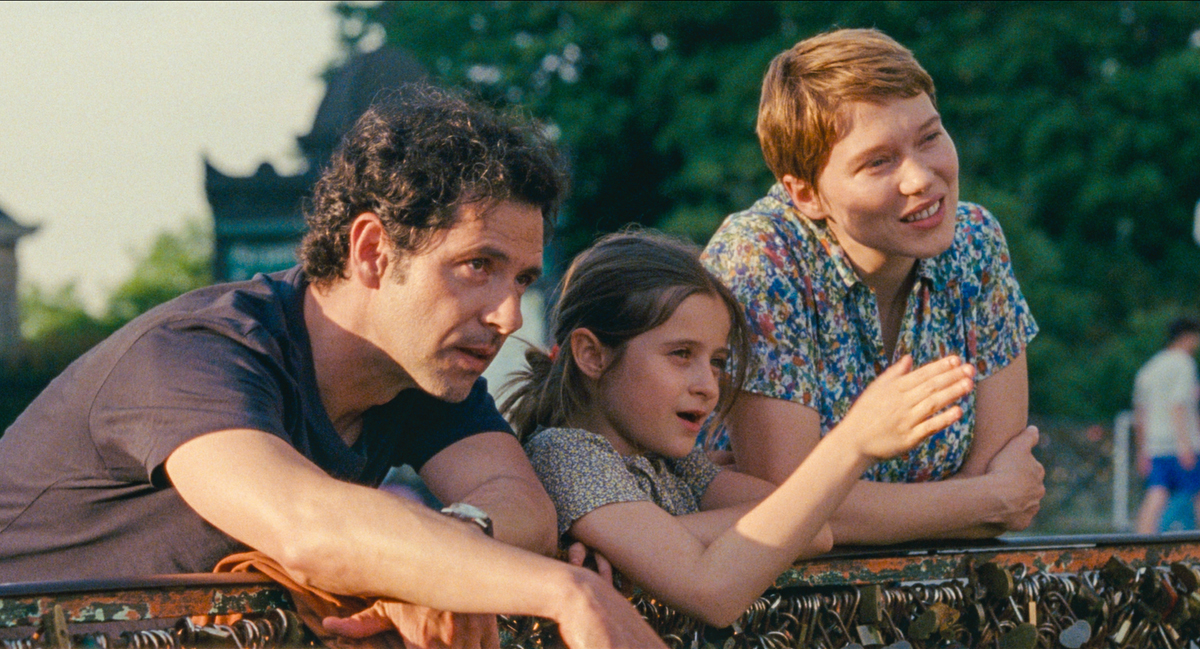

Melvil Poupaud as Clément, Camille Leban Martins as Linn, and Léa Seydoux as Sandra in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

One Fine Morning, written and directed by Mia Hansen-Løve, now playing in theaters

• • •

Imagine the shock of discovering that your husband’s mistress is Léa Seydoux. I see it playing like an extended cut of Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come (2016), when, at the beginning of the film, the spouse of Isabelle Huppert’s character sits her down and calmly tells her that he’s fallen in love with someone else. Huppert’s Nathalie only ever glimpses the other woman on the street, but in this Léa-fied version, the adulteress enters the spotlight, her sundry charms shamelessly on display: her come-hither tooth gap, her cheekbones like seraphic blades. There’s something so stereotypically mistress-like about Seydoux. Bond girl, muse (The French Dispatch, Deception), magnetically stoic beauty, she’s an actor who carries herself with the control and self-possession of a woman shrewd in the ways of the world. But Léa’s cool is hot to the touch. She also radiates passion, actively trying to stave off its eruptions but occasionally failing. Funny that the actor has an uncanny ability to fill her eyes with tears on command, a skill exploited time and again—in Falconetti-esque close-up—by her directors. You can see Huppert’s eyes rolling from a mile away.

A mistress figure is precisely the woman at the center of Hansen-Løve’s One Fine Morning. Played by Seydoux, she’s as lusty and coquettish as the cliché presumes—but she is also more than this. A seasoned translator and a single mother whom we meet five years after the death of her husband, Seydoux’s Sandra walks around the polished parts of Paris in stonewashed boyfriend jeans and cozy pullover sweaters, her hair trimmed short à la Jean Seberg. Hansen-Løve follows Sandra as she weaves through different spheres of her life—cuddling her feisty daughter, Linn (Camille Leban Martins), in their pocket-size Right Bank apartment; providing live, simultaneous translations between French, English, and German for commemorative ceremonies and professional conferences; rekindling her friendship with cosmo-chemist Clément (Melvil Poupaud), the married father of Linn’s classmate and Sandra’s soon-to-be lover.

Léa Seydoux as Sandra and Melvil Poupaud as Clément in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

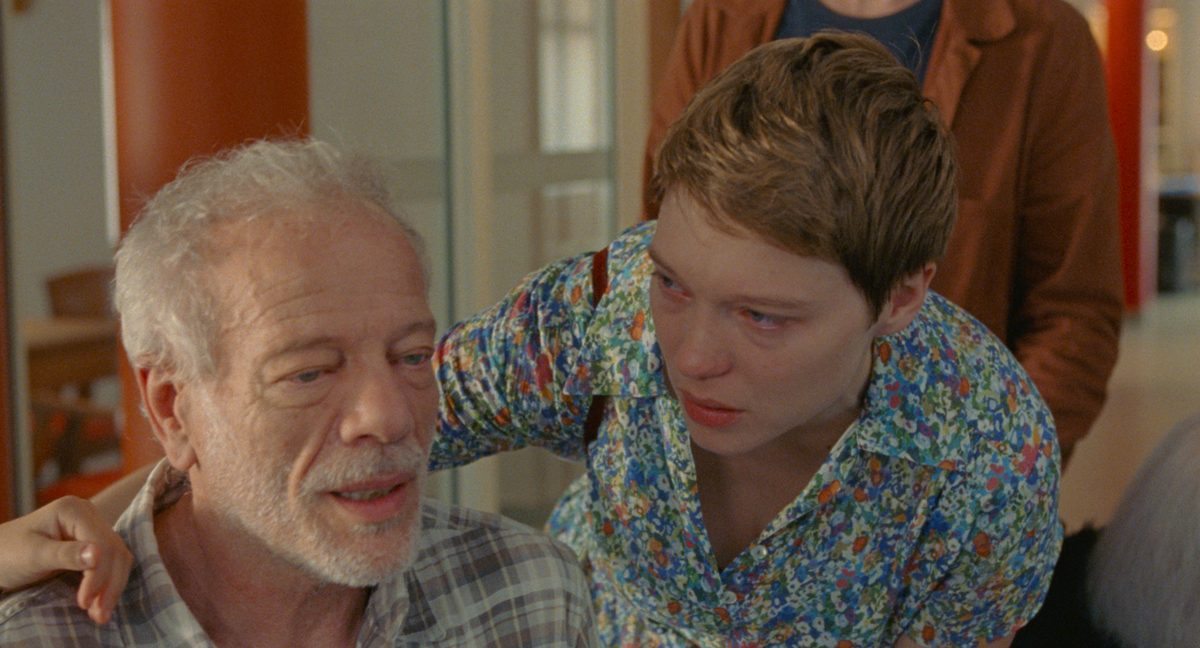

In contrast with the everyday banalities and the highs and lows of her new romance, however, is a grim reality that mirrors the circumstances of the death of Hansen-Løve’s own father in 2020—the latest seedlings for a filmmaker who has always used the facts of her own life as a point of departure. Sandra’s father, Georg (Pascal Greggory), a tender retired philosophy professor, is succumbing to the degenerative effects of Benson’s syndrome, forcing Sandra—along with her mother and sister—to regularly tend to him as he relinquishes his flat and makes his way through a series of nursing homes. When we first meet Sandra, she’s standing outside Georg’s apartment, guiding him from behind the door as he struggles to turn the knob. He’s not just sick, he’s lost. Alive, yet denuded of that which once defined him: his memories, his work, his favorite writers and musicians. Everything and everyone is fading, save his partner, Leïla (Fejria Deliba), who—from Sandra’s perspective—appears only intermittently by his side.

Léa Seydoux as Sandra and Pascal Greggory as Georg in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

But then, Clément is not so different. Over the course of the year in which the film unfolds, Clément goes back and forth between his unseen wife and Sandra—racked with guilt and an obligation to his child, on the one hand, and gripped by his longing for Sandra on the other. It would be easy to think of such a conflicted character as toxic, especially one who too often mutters risible sweet nothings when he’s horny. But whatever my feelings about the appeal of Poupaud, I’m not sure Hansen-Løve means to seriously question Clément’s love—or Leïla’s for that matter—by demarcating his frequent absences.

Nicole Garcia as Françoise and Léa Seydoux as Sandra in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

“I voted for Macron, but I’m against him,” quips Sandra’s pseudo-activist mother, Françoise (Nicole Garcia), in a bit of comic relief that underscores the inconsistencies in Sandra’s life: she mourns a father who is not dead; she is in love with a man bound to another woman; she makes her living communicating meanings dictated by other people. Another filmmaker might interpret these contradictions as the root of an existential crisis. But Hansen-Løve spins them into the stuff of poetry, held in balance by an inner resilience less exceptional than it is necessary—the very nature of passing through time as a human made up of different pieces and textures.

One Fine Morning envisions Sandra’s life as a current, flowing in and out of moods with the momentum of a Métro ride and its myriad pauses, its sudden malfunctions. Seydoux’s gifts prove preternaturally suited to such a vision of life’s oscillations: on a bus, in the wake of a particularly demoralizing visit with her father, she receives a text from Clément. He is still in love with her. Seydoux gasps without gasping; her face clenches and falls slack before succumbing to tears laced with relief and satisfaction. It’s as if a coat of optimism has painted over—but has not obscured—the grief that inaugurated the moment. The film is filled with such steep waves of feeling.

Pascal Greggory as Georg and Léa Seydoux as Sandra in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

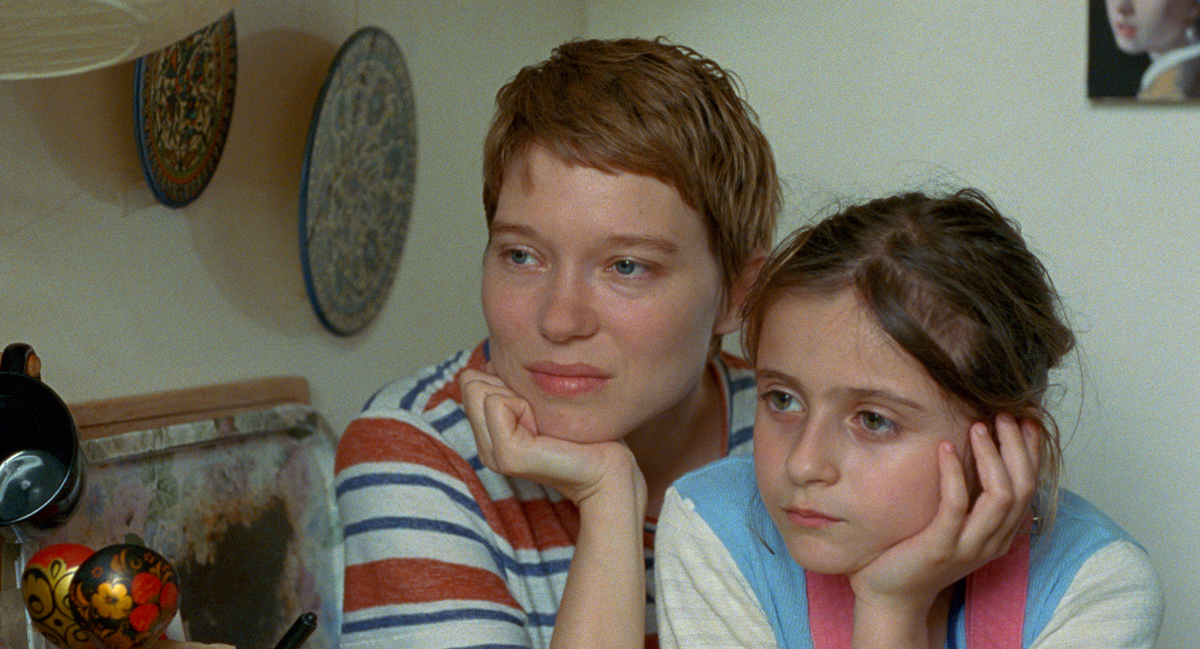

More than Hansen-Løve’s previous films, One Fine Morning is an intergenerational portrait, one bound by the act of perceiving. Greggory’s crystal-blue eyes take on a dazed milkiness under the fluorescent lights of the nursing home; asked by Sandra to describe the length of her hair and the pattern of her dress, Georg murmurs a string of non sequiturs. It is a sad fate for a man who had once been dedicated to the pursuit of “clarity and rigor.” Motifs of seeing and mastering are sprinkled throughout the film: in the phone app that allows you to identify the trajectory of a plane; in the machine at Clément’s office that performs all manner of nebulous analyses. But Hansen-Løve is concerned with emotional knowledge. “That’s not very nice,” says Linn, smiling impishly when she realizes her mother sometimes doesn’t answer the phone calls of her ailing, burdensome grandfather. She giggles when she slips into her mother’s bed at night and, eyes wide, sees Clément—known up to this point only as “Jérémie’s father”—resting beside her.

Léa Seydoux as Sandra and Camille Leban Martins as Linn in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

Marguerite Duras once wrote of a “suspended passion,” a force that remains fixed in the world, waiting to be seized by those willing to seize it. If nothing else, passion is the film’s one anchoring force, what remains beyond personal history and reason and words. Georg’s yearning for Leïla is the sole robust aspect of his diminished body, the only instrument capable of cutting through the haze. Meanwhile, Sandra, caught up in the ceaseless tide of work, mothering, and filial responsibility, finds clarity and stillness in brief stretches of carnal rapture, in the urgency of libidinal truths.

Léa Seydoux as Sandra and Melvil Poupaud as Clément in One Fine Morning. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics. Photo: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas.

At a family Christmas gathering, Linn and her cousins are dazzled by an obvious fiction. Instructed to wait in the other room so Santa can deliver the presents, the girls press their ears to the door as the adults knock around and put on phony voices as if Père Noël himself were crashing through the window. Perhaps desire is only as powerful as the illusions and hopes that sustain it: sightless Georg, frozen in a state of anticipation, not knowing when Leila will appear; Sandra, checking her phone, praying for a sign from Clément. In the final scene, having fled Georg’s nursing home, Sandra, Linn, and a conclusively committed Clément admire a panoramic view of Paris from the limestone steps of Sacré-Coeur. The spring day is magnificent. Clément points to the Eiffel Tower, to the location of Sandra’s apartment. The canvas is simultaneously clear, unclouded, and infinite—shimmering with the unknown.

Beatrice Loayza is a writer and editor who contributes regularly to the New York Times, the Criterion Collection, Artforum, Film Comment, Cinema Scope, the Nation, and other publications.