Beatrice Loayza

Beatrice Loayza

Woodcraft, warcraft, witchcraft: Pietro Marcello’s latest film blends realism and fantasy to tell a meandering tale of a father, daughter,

and their makeshift family.

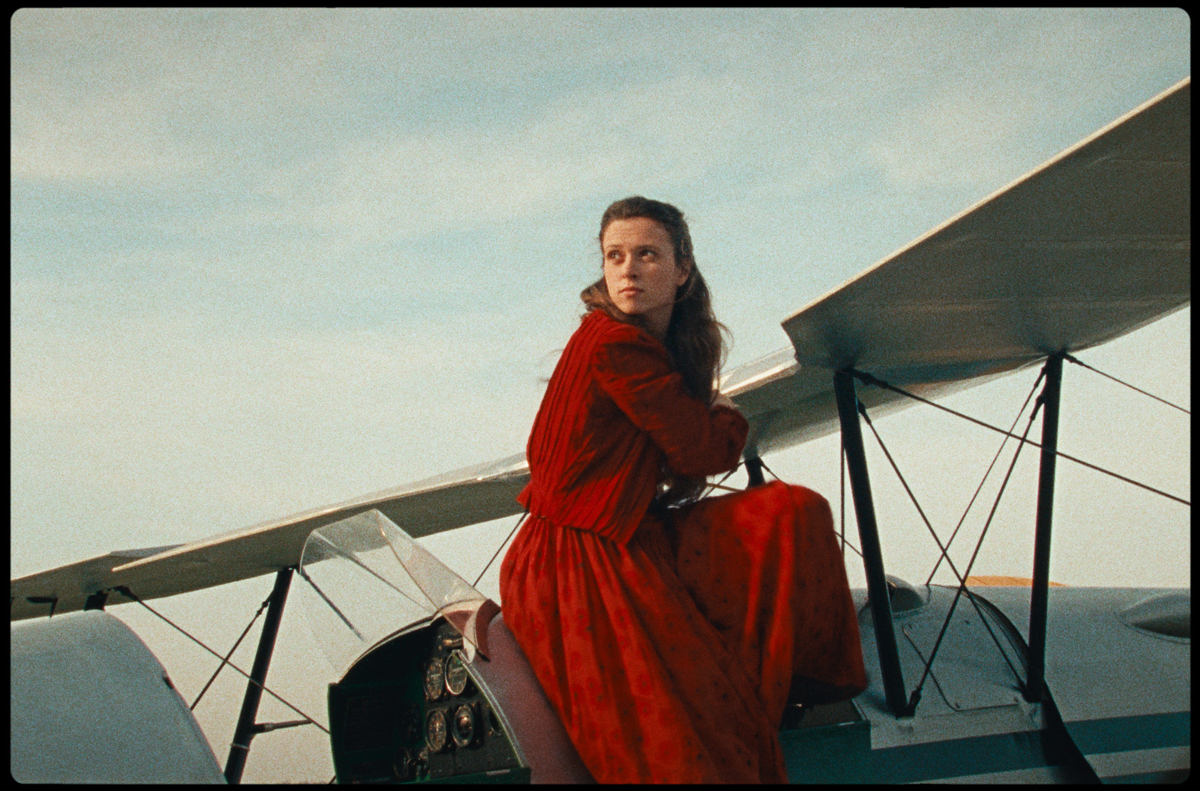

Juliette Jouan as Juliette in Scarlet. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Scarlet, directed by Pietro Marcello, now playing at Film at Lincoln Center, New York City

• • •

A burly foot soldier, Raphaël (Raphaël Thiéry), practically bursts out from the pallid archival footage of homeward-bound troops that opens Pietro Marcello’s Scarlet. The year is 1918. World War I has ended, the age of modernity ushered in by the unprecedented scope of its bloodshed and its fallen empires—a rebirth achieved with startling efficiency by military technologies and the tireless churn of industrialization. Raphaël, in contrast, looks like a mythic being carved by time, his blue eyes like glass beads sewn into a craggy visage wrought with clay and fire. As in sundry classic Greek tales, Raphaël, too, comes home to a dead wife, who was raped before essentially taking her own life. What remains is a child, fair Juliette, the Artemis to her father’s Zeus, born into a world in which people have lost their religion.

Marcello’s previous feature, Martin Eden (2019), his first venture into narrative filmmaking, is a stunner, a decades-spanning saga of Faustian dimensions that tracks a history of twentieth-century Italy through the individual story of a benighted sailor who strives for, and eventually attains, literary fame. For that movie, Marcello expanded upon, rather than abandoned, the fusionist practices that defined the first part of his career as a director of experimental documentaries with an ethnographic bent (The Mouth of the Wolf, 2009; Lost and Beautiful, 2015). An adaptation of the Jack London novel of the same name with a coastal Italian twist, the film is an exuberant Künstlerroman with all the sweep and quivering tragedy of a classic Hollywood epic yet also, somehow, bigger than the Great Man at its center. A kind of collective historical unconscious seeps in courtesy of temporal anachronisms and archival interludes.

Raphaël Thiéry as Raphaël and Sienna Gillibert as Juliette in Scarlet. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Scarlet—which plays like a humble, slender folk tale where Martin Eden carries the heft of its source tome—takes Marcello north, to a rural outpost in Normandy, France. Archival footage, beautifully restored and occasionally tinted, is less aggressively employed relative to Martin Eden. Funereal scenes of postwar trekking and, later, bustling Parisian alleyways and luxury markets stitch together the episodes of Raphaël and Juliette’s lives, anchoring them as participants in a very real history. (Marcello has noted that cost was a crucial motivation for including old footage—for a movie with a budget well under ten million euros, archival clippings lend an uncanny force to the fictional proceedings that a shoddily reconstructed set would only cheapen.)

Yet the film, even in the social-realist mode of its first half, wherein a shaky camera captures Raphaël’s tortured homecoming with the gloom of a Dutch still life, possesses a magical quality—thanks in no small part to the score by Gabriel Yared. Yes, the veteran composer may be responsible for some of the corniest soundscapes in modern cinema (The English Patient, 1996), but his riff here on the more elfin, otherworldly tunes of The Nutcracker or Sleeping Beauty gives Scarlet its sustained ambience of naive wonder.

Funny that Raphaël, brute that he appears, is actually a softie—an artist, his bulbous paws skilled in carpentry and woodwork, specifically the fabrication of children’s toys. Taken in by a widow, Adeline (a feisty Noémie Lvovsky), with whom his wife had previously lived and who is now raising Juliette, Raphaël soon adopts the household’s scarlet reputation. When he learns that Fernand (François Négret), a mustachioed bar owner and village leader, is the man behind his beloved’s death, he channels his fury into chopping wood and playing his accordion—and then stands idly by when he stumbles upon the wretch screaming for help as he nearly drowns in a bog. While rape is no big deal for the townspeople, Raphaël’s refusal to aid Fernand brands him persona non grata along with the witchy Adeline and the immigrant family who also live under the matriarch’s roof.

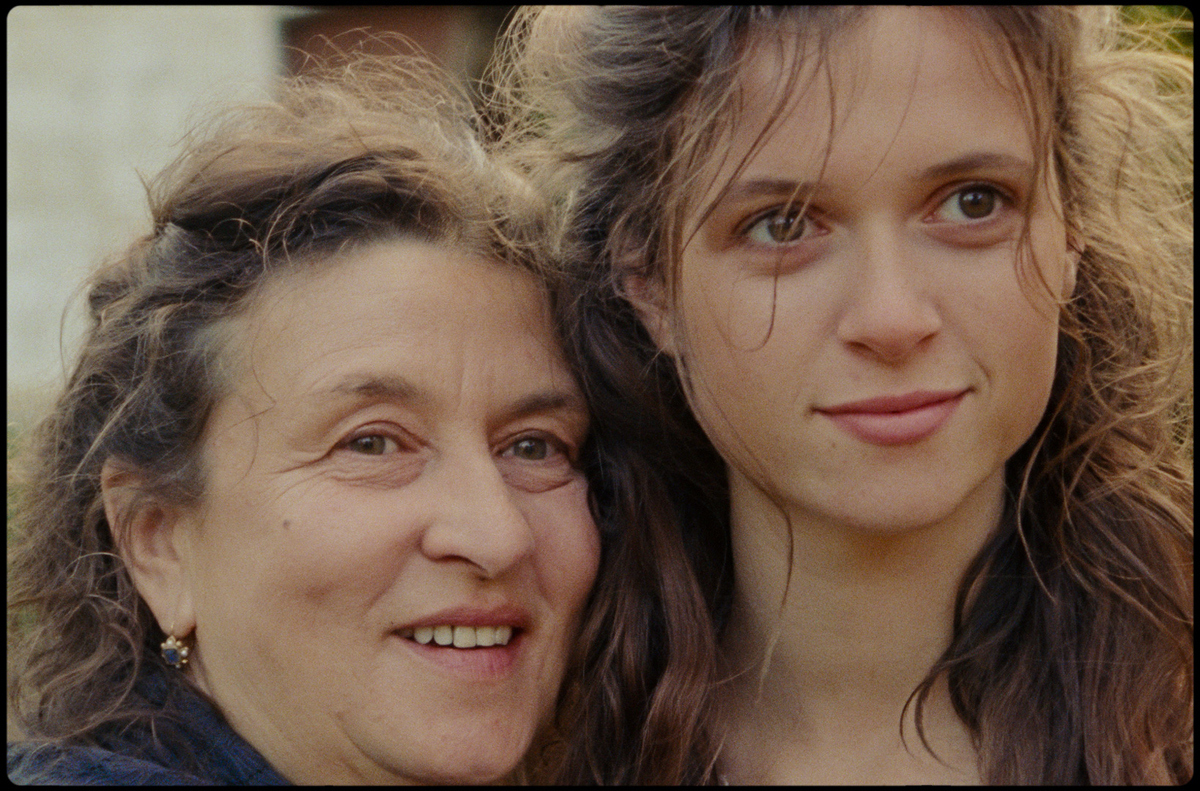

Noémie Lvovsky as Adeline and Juliette Jouan as Juliette in Scarlet. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Adeline is a fortune teller, gleaning the future’s promises from black powder sprinkled over a plate of water. She, like Raphaël, makes “so-called miracles with [her] own hands,” to borrow from the epigraph that opens the film, a passage from the 1923 source novel, Scarlet Sails, by the Russian author Alexander Grin. Sorcery—like art—is an intuitive undertaking, the creation of something fantastic, sublime, rendered by the learned skills of mere mortals. Raphaël designs miniature sailboats whose delicate qualities appear at odds with their hulking maker—though Juliette may be his ultimate creation. The girl is an impossibly graceful yet vivacious presence, embodied initially by three child actors before assuming her adult form (Juliette Jouan, a first-time actor plucked from obscurity following a public casting call).

Juliette Jouan as Juliette in Scarlet. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

The second half of the film, dominated by a fully grown Juliette prancing through tall grasses in crimson frocks and milky slips, pivots more forcefully into the realm of fantasy. A gifted songstress and craftswoman in her own right, Juliette fends off the temptation to conduct her studies in the city, bypassing the predictable coming-of-age trajectory of the country naïf thrust unto worldly urbanity. Marcello employs a slippery editing style, weaving glimmering 16mm footage of flora and fauna into subtly whimsical slivers of Juliette’s life—her encounters with a cherubic forest witch (Yolande Moreau); a conversation with a magpie, visualized as a cartoon when it takes flight; bursts of song that recall the swooning musical confections of Jacques Demy. There are monsters, too: Fernand’s lascivious son, Renaud (Ernst Umhauer), is hellbent on possessing Juliette. A Prince Charming–type, Jean (Louis Garrel), literally falls from the sky as a rakish pilot-adventurer, briefly pulling the film into his bewildered point of view.

Juliette Jouan as Juliette and Louis Garrel as Jean in Scarlet. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

“You should’ve died in the war,” the mobbish townspeople tell Raphaël, who, in the final act, carves an elegant figurehead in the likeness of his wife. “I didn’t know they still made those,” says Adeline, an observation that extends to the wooden toys Raphaël crafts for a living. His regular customer, a Parisian toy-shop owner, explains they’ve fallen out of fashion. Children now prefer things that move on their own, mechanical trains as opposed to inert wooden boats that require an added layer of imaginative investment. Later, Juliette becomes an artisan of stringed instruments—a beautiful but wildly unprofitable occupation that runs counter to the era’s swell of mass production and artless commercialism.

Throughout the interwar years in which Scarlet takes place, cinema took hold as the most plastic, most obscenely mercenary industry. Yet in her first trip to the toy shop, young Juliette is gifted a zoopraxiscope, the cinematic prototype conceived by Eadweard Muybridge, anchoring what follows to cinema’s origins in optical illusion. Early cinema, like magic, conjured dream images from the materials of real life, beckoning audiences to enter a state of enchantment beyond reason. Perhaps that’s why Juliette only ever fantasizes about traveling abroad, her native fairyland like the frame of a camera. Only here could Jean’s leg, mangled by a crash landing, heal instantly with a few mystic mutterings from Adeline. He walks and we believe it.

Beatrice Loayza is a writer and editor who contributes regularly to the New York Times, the Criterion Collection, Artforum, Film Comment, Cinema Scope, the Nation, and other publications.