Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

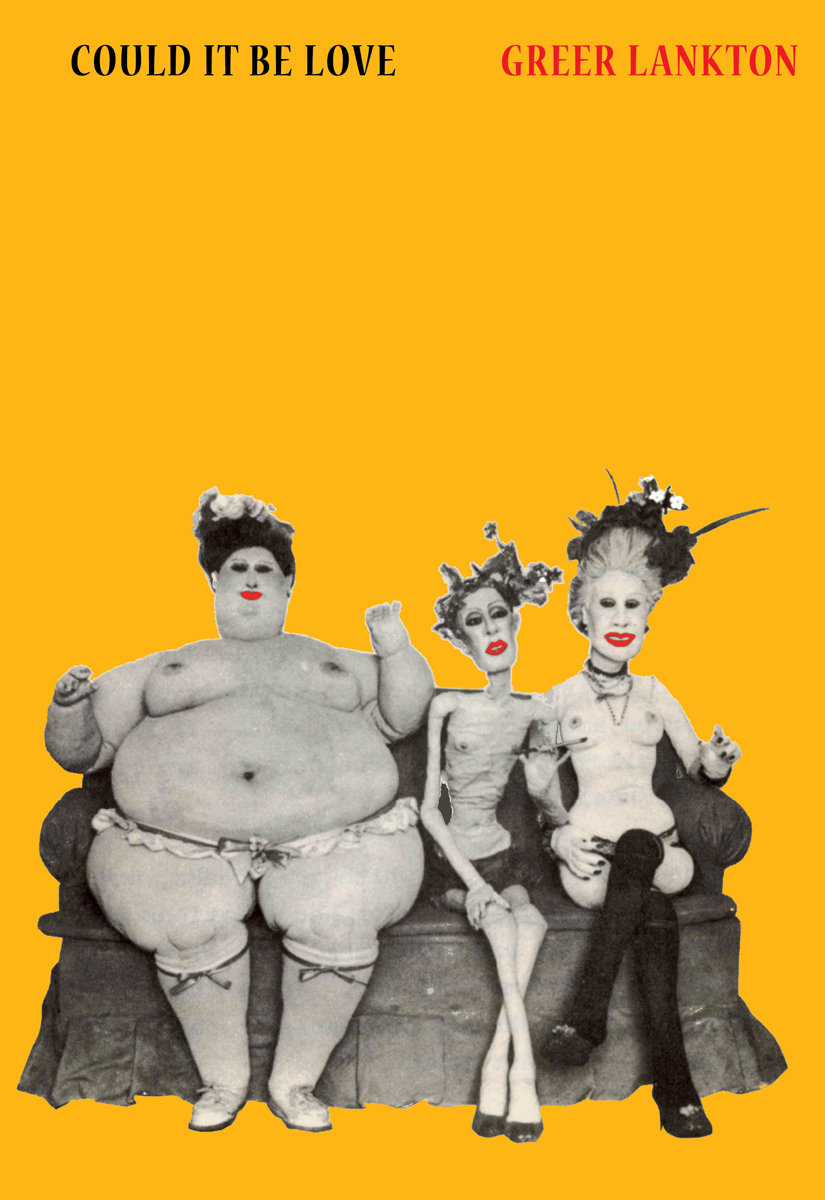

The first monograph of artist Greer Lankton’s defiantly disturbing

doll tableaux.

Could It Be Love, by Greer Lankton, edited by Francis Schichtel, Jordan Weitzman, and Nan Goldin, Magic Hour Press, 139 pages, $50

• • •

Greer Lankton’s artist statement, written shortly before her death, contains almost everything you never wanted to know about her:

I’ve been in therapy since 18 months old, started drugs at 12 was diagnosed as schizophrenic at 19, started hormones the week after I quit Thorazine got my dick inverted at 21, kicked Heroin 6 years ago. Have been Anorexic since 19 and plan to continue and you know what I say FUCK Recovery, FUCK PSYCHIATRY Fuck it all because I’m over it. Over the roof. I’m so sick I’m dead, so from now on I take no responsibility for my actions. Oh and I was fucked up the ass by my grandfather since age 5, been brutally raped twice and have had almost every major organ in my body fail at some point. Life support is no picnic for Rhoda so don’t EVEN take me there. By the way I’m an artist and Andy Warhol was the dullest person I ever met in my life. But he’s got a museum so what do I know. Hans Bellmer is my favorite artist.

What interests me isn’t the biographical trivia but the tone in which it’s delivered: confrontational, flippant, pitiless—a theater of bludgeoning disclosures. It’s language that mirrors the pathological and psychosexual intensity of Lankton’s art, although it doesn’t tell you what that art’s about, unless you linger on the invocation of Hans Bellmer.

Like Lankton, Bellmer made disturbing dolls and then photographed them. His models are often disjointed, or bulbous, or have legs where their arms should be. They look like women who fell apart and were rearranged by a sadistic fetishist. Created in Germany right after Hitler’s ascendancy, Bellmer’s malformed poppets were envisioned as an affront to the Nazi ideal of the “perfect” body.

From Could It Be Love. Courtesy Magic Hour Press.

Lankton’s dolls, too, transgress their own regimes of beauty, youth, and health, although many of hers look like they’re enjoying themselves considerably more than Bellmer’s. In the early 1980s, she displayed them in the window of Einsteins, an East Village boutique, where they lounged like junkies or preened like expired starlets, usually life-size, posed in tableaux that only intensified their strangeness. Lankton became a luminary and muse in the much-mythologized downtown art scene. She was included in P.S. 1’s seminal New York / New Wave show in 1981, exhibited several times at Civilian Warfare Gallery, and moved among friends like Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz, and Peter Hujar, though she remained a cult figure, more urban legend than museum fixture. The curator Diego Cortez called her a pioneer “who blurred the line between folk art and fine art”—typically not the sweet spot for posterity.

Could It Be Love, Lankton’s first monograph, renders her legible as an artist, not merely a tragic curiosity. It reaffirms her as the most genuinely provocative and visceral presence to come out of that storied East Village heyday. Coedited by Goldin and the photographers Francis Schichtel and Jordan Weitzman, the book features only one brief essay: an affectionate if cursory tribute by Hilton Als. Otherwise, it’s just page after page of photos that capture the variations and affinities of Lankton’s more than three hundred dolls—like a family for whom inbreeding has introduced mutations, but whose blood ties are unmistakable. Some of the photos have the bruised immediacy of Goldin’s, or the reverence of Hujar’s. A few read like ripostes to fashion ads, such as the image of a topless and hospice-thin doll striding down the beach in a makeshift sarong and heels.

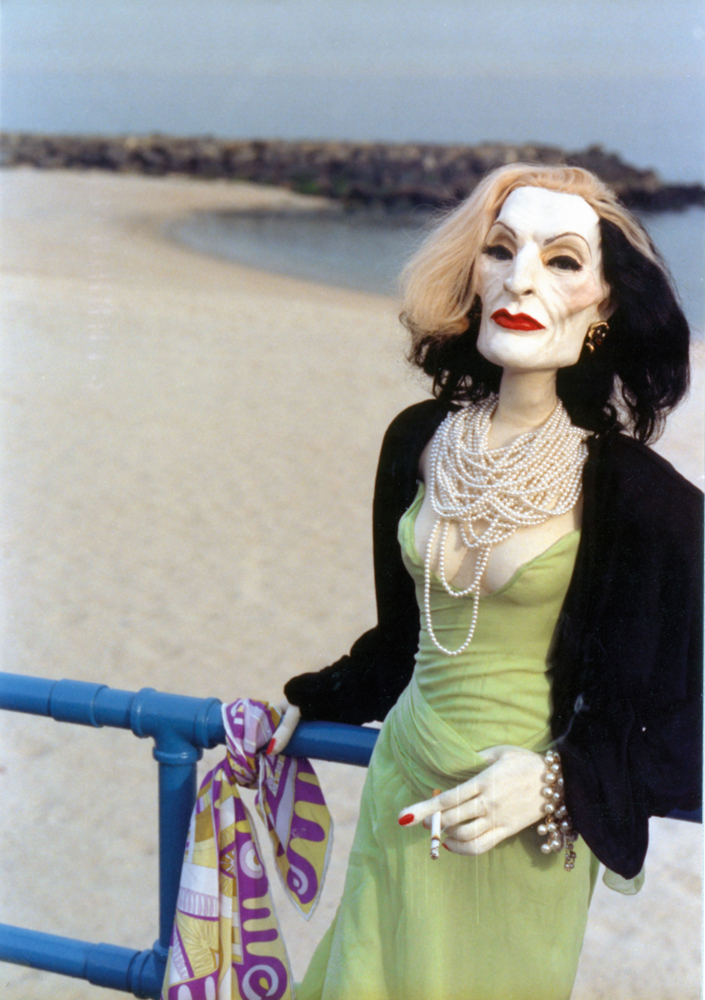

From Could It Be Love. Courtesy Magic Hour Press.

That doll, Grandma Tillie, recurs throughout the book, wigless at one point, brandishing a birthday cake at another, always appearing delighted to be there. Lankton’s many other original characters include the chic but desiccated Sissy; the gnarled aristocrat Lady Demerol; and a few—Melvis the Fat Lady, Harold the Pinhead, the Pater Twins—inspired by sideshow freaks. A handful are modeled on underground icons like Candy Darling, Ethyl Eichelberger, and Divine. Made with wire armatures and papier-mâché, several are fitted with dentures or glass eyes procured from a local taxidermist, lending them an unnerving vivacity. They morph over time, bloating and starving, changing clothes and hairstyles, endlessly reinventing themselves.

Lankton’s dolls are almost always seen as surrogates, personifying her struggles with anorexia, gender dysphoria, and drug addiction. But Could It Be Love is a record of the body as an ongoing rehearsal, perpetually broken and reconstituted. More than avatars of suffering, the dolls are performers, satirists of beauty, comedians of identity. What strikes me as I encounter them is their self-possession. They’re not necessarily happy, but they embody their ruin with singular éclat.

From Could It Be Love. Courtesy Magic Hour Press.

A photo that guts me every time depicts one of Lankton’s rare male players—Uncle Earl, sort of a pickled John Candy—slow-dancing with a skeletal man. Earl has a hand-rolled cigarette in his mouth and a faraway look in his eyes; his partner, pallid and incurable, leans in as if savoring this blessing of human touch. The scene reminds me of those moments of drunken bonhomie you sometimes experience around last call, when brokenhearted barflies agree to briefly console each other, using liquor as their alibi. It’s an image that refutes the standard conception of Lankton’s work as grotesque or defiled.

Not that that conception is unwarranted. Late in the book is an image of the desperately malnourished Aunt Ruth, vamping in a grungy Vivienne Westwood-esque dress, her eyes apparently gouged out and a cross carved into her chest. The image could easily moonlight as the poster for some prom-night giallo flick. Then there’s the photo of Sissy lolling naked in bed, applying garish lipstick that echoes the inflamed nub of her penis. Most unsettling is the penultimate photo: Sissy dismembered on the floor, panties around her ankles, her makeup jarring in its enticement.

From Could It Be Love. Courtesy Magic Hour Press.

There’s composure even in these scenes of desecration, a sense that destruction itself has become performance. Could It Be Love concludes with something Lankton told I-D Magazine in 1984: “The prettiest people are the blandest.” Yet, ironically, her dolls achieve a tarnished seductiveness. You can’t look away from them, nor can you possess them—the paradox of beauty. Like the figures in paintings by James Ensor or Egon Schiele, Lankton’s dolls exist in a queasy twilight between tragedy and farce. You’re moved to pity them, to be repelled by them, but they’re sovereign outsiders. They don’t need your sympathy: FUCK your sympathy. Their magnetism isn’t redemptive—it’s defiant, the purity of someone who’s endured her own dismantling.

In 1991, exhausted by the inescapability of AIDS and hoping to get sober, Lankton left New York for Chicago, where she’d grown up. She converted her modest studio apartment into a shrine of celebrity headshots, religious kitsch, and doll parts. Her final project—titled It’s All About ME, Not You—was a recreation of that apartment at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, which opened shortly before her fatal overdose in November 1996, when she was thirty-eight. She weighed about ninety pounds when she died, a blonde on the verge of vanishing, but glamorous in a way that’s unseemly to admit.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.