Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

Queer beefcakes, rotten teeth, and dinner with a horse: the lives

of rebel royals.

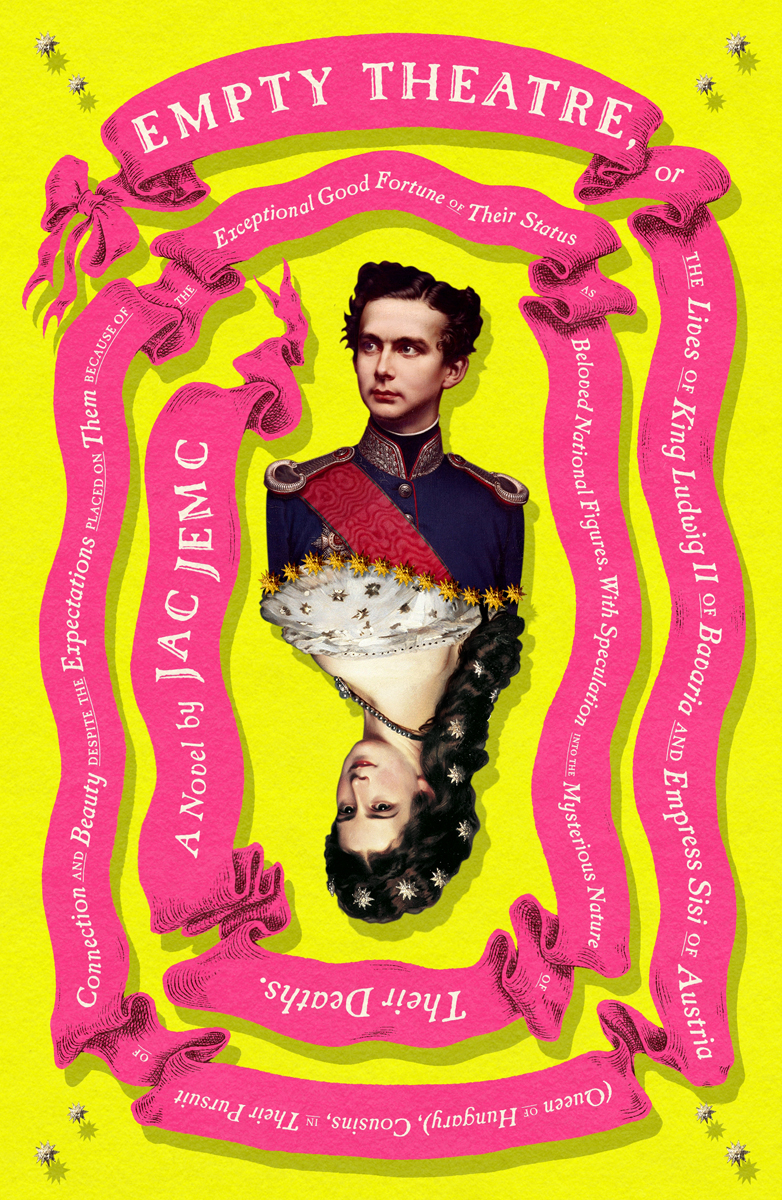

Empty Theatre, by Jac Jemc, MCD, 451 pages, $14.99

• • •

King Ludwig II of Bavaria—the Swan King, the Dream King, the Fairytale King, the Mad King—is a figure whose extravagance almost exceeds the ingenuities of fiction. How can a novelist hope to improve on the phantasmagoria of Ludwig’s life? He ascended to the throne at eighteen, a candied twink in the mold of Young Werther, moody and star-crossed, more enthralled by operas than statecraft. He was the infatuated patron of Richard Wagner, to whom he issued villas, money, and artistic ultimatums. He built castles the way other people build resentments: delusionally and lavishly, with little regard for function. He was closeted and carried on secret trysts with a male coterie that included his aide-de-camp, his equerry, and a Hungarian theater actor. Legend has it that as Ludwig grew more reclusive, his beloved horse, Cosa Rara, was brought indoors to dine with him. In 1886, in debt and still fantasizing new architectural fiascoes, Ludwig was deemed insane and removed from power. (His cabinet paid—or bribed—palace flunkeys to supply incriminating evidence.) Shortly after, his body and that of his doctor were found floating in the shallow water of what was then called Lake Würmsee, south of Munich. Ludwig’s death was declared suicide by drowning. An autopsy revealed no water in his lungs.

In her novel Empty Theatre, Jac Jemc recounts the brief life and decadent reign of Mad King Ludwig. But she also tells a parallel story: that of Ludwig’s cousin, Empress Elisabeth of Austria, nicknamed Sisi. Like Ludwig, Sisi came to power young; she was sixteen when she married Emperor Franz Joseph I. Her life in the Habsburg court was restrictive: emotionally, given that she was treated primarily as the imperial uterus, and physically, given her severe diet and reliance on corsets. (Sisi was proclaimed “the most beautiful empress in Europe,” a title she was loath to relinquish as she aged.) Her domineering mother-in-law, Archduchess Sophie, took over rearing Sisi’s children, one of whom died as a toddler, lending the Empress a bereaved mystique that never faded. Indeed, that mystique deepened after her eldest son and his teen mistress died in a murder-suicide pact. A grieving Sisi retreated from court life and built her own opulent palace on the Greek island of Corfu. In 1898, while traveling incognito in Switzerland, she was stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist.

What connects the two royals in Empty Theatre, beyond their bloodlines, is a petulant rebelliousness. “Once you have everything, you must continually dream up new things to want,” Ludwig quips late in the novel, a sentiment that animates him and Sisi, and that gives their antics the quality of rancid meringue. On the eve of becoming king, a panicked Ludwig flees on horseback to the mountains, where he crashes with a bewildered peasant family. “I believed I had a whole lifetime to do something else before the mantle fell to me,” he whines. The family, ambushed by this guest who has the authority to behead them should he so wish, is keen to show hospitality. They invite the future king to stay the night, and having “not been trained to refuse things out of politeness or to know when he has overstayed his welcome,” Ludwig accepts.

Jemc could have exaggerated the inherent absurdity of this scene (and various others like it), but instead she plays it mostly straight. Throughout the book, she seems to waver: Is she writing a tragicomic confection, à la Sofia Coppola’s film Marie Antoinette (2006), or something trickier—a biographical novel virtually devoid of interiority, narrated by the panoramic voice of Fate? (After all, the three-page prologue, subtitled “An Omen,” is a litany of spoilers: “because the story will unfold no differently if you learn the outcome now or later, because the ending will confound you no matter where it finds you, because if you combine enough answers they don’t look much different than a question.”)

The approach Jemc settles on is a middle path between satire and family drama, although it’s hard to satirize figures who were, from birth, already caricatures of cloistered, bored, wanton nobility. Symbolism becomes overripe (Sisi’s immaculate face conceals a mouthful of rotten teeth), and psychology is conveyed with rude efficiency, as when Sisi tells her son a story about the longings of a runaway horse, or when young Ludwig buys a porcelain figure of William Tell and rubs the “rosy cheeks and cleft chin so much that the glaze starts to dull.”

Occasional anachronisms—small and large—deflate the pomp of Jemc’s imagined world. Sisi is described as a “twerpy accessory to the Emperor”; one of Ludwig’s male paramours is introduced as a “beefcake.” Sisi’s brother-in-law, LV, is a flaming bon vivant of the Quentin Crisp style who calls himself a “lady” and sees in Ludwig a kindred spirit. (The real-life LV, Ludwig Viktor, aka Luziwuzi, was exiled to the outskirts of Salzburg after propositioning a military officer in a public bathhouse.) If LV is the campy sock of queerness, then Ludwig is its tortured buskin. His barely smothered sexuality is symptomatic of other existential and social constraints, and is the sine qua non of his self-denial. “Only in the dark is Ludwig able to permit himself what he truly wants,” Jemc writes. Ludwig is embodied by his queerness. During an assignation with an actor summoned to the palace, “a tight acid rises in [Ludwig’s] throat,” “flames dilate in his stomach,” and he feels “a dissolving pressure in his anus.” There’s nothing like a blow-job scene to make even a nineteenth-century monarch feel—as MFA students would say—“lived-in.”

And so queerness is another cage—like royalty, like reality—from which Ludwig can’t escape. The history in Empty Theatre isn’t so much revisionist as retrofitted. It’s a narrative strategy that falters only near the end. The novel’s brief penultimate chapter, “A Meditation,” begins: “What is loneliness? Telling one’s story, when no one will listen. Not sharing one’s truth out of fear. Letting others dictate one’s narrative, none of the versions just right.” There’s a whiff of the corporate copywriter in these lines, a patronizing syrupiness that recalls, say, an ad for Zoloft. The meditation is an all-purpose benediction: it frames Ludwig’s sexuality within the requisite liberal pieties; it throws a feminist gloss on Sisi’s stifled autonomy; and it alludes to the generalized alienation of people cast in roles they don’t want. But the tone sterilizes some of the bombast and madness of the preceding four hundred–plus pages, squeezing Ludwig’s singularity into a familiar, four-cornered emotion like loneliness. Here, perhaps, is what fiction offers that conventional biography doesn’t: a nugget of moralizing psychology in lieu of a denouement. Still, as a story of royals behaving badly and bemoaning their privilege, Empty Theatre has impeccable timing. Such stories have never gone out of fashion. They even used to be interesting.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.