Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

Butchered and bagged: Elon Green explores the murders of four gay men in early ’90s New York City.

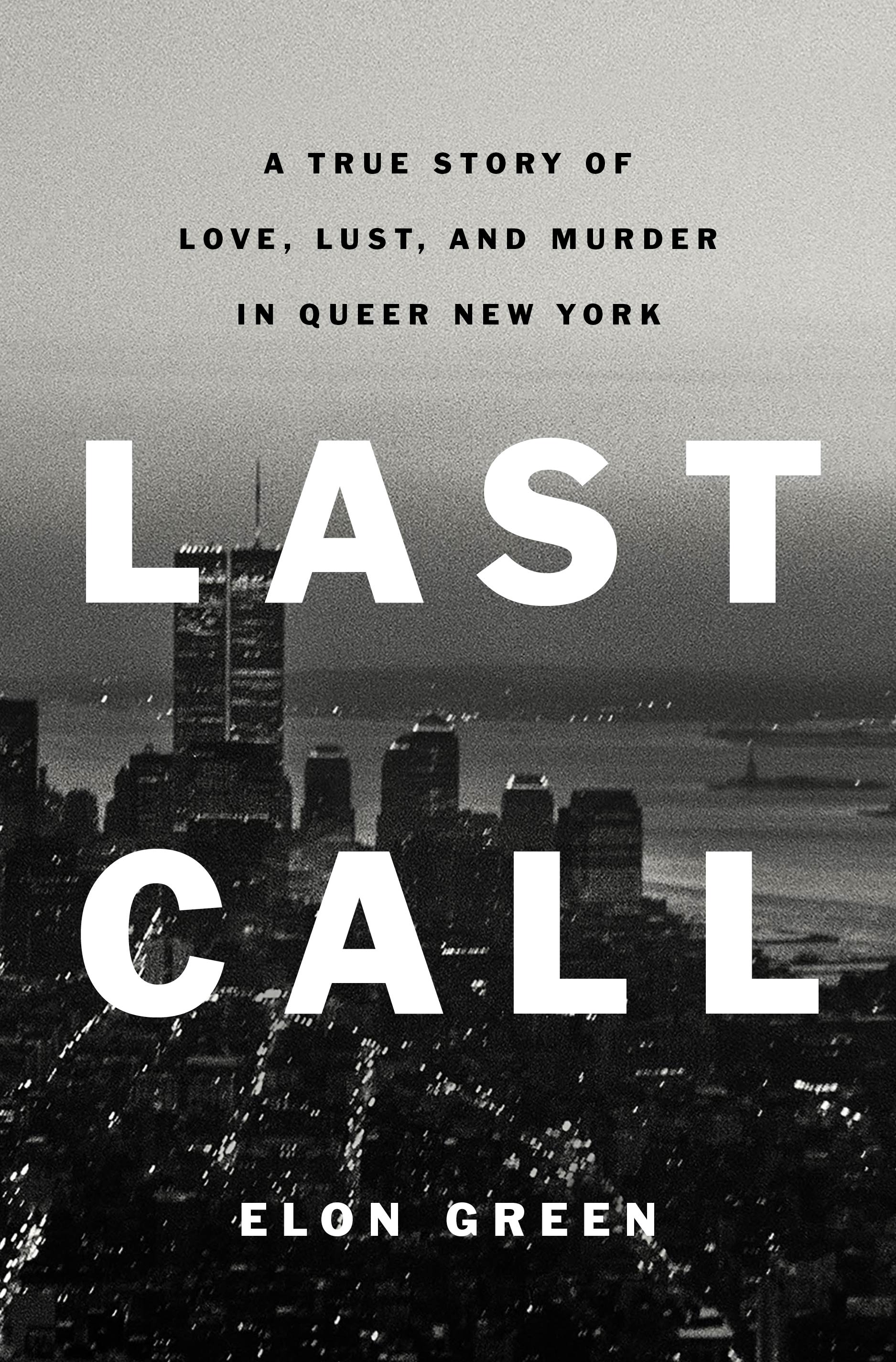

Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York,

by Elon Green, Celadon Books, 255 pages, $27

• • •

In November of 1976, a New York City drag queen named Toni Lee was strangled to death in her MacDougal Street apartment. The murder chilled the city’s gay-bar crowd, already on edge after a series of dismembered bodies washed up along the notoriously cruisy Hudson River piers—crimes the NYPD allegedly dubbed the “fag in a bag” murders. Arthur Bell, a gay journalist at the Village Voice, sensed a fatal nonchalance in the atmosphere of nighttime Manhattan, a sexual voracity that would prove, for many, the tragic denouement of the Stonewall generation. “[Bars] are combat zones where customers seek out peak thrills, the ultimate thrill being a matter of individual taste. Each time you think you’ve gone as far as you can, a new taste treat looms on the horizon,” he wrote in 1977, adding, ominously, “Deep in the night, you often ask yourself how far you are from a place called the Hospital.”

In the early ’90s, gay men in New York again had occasion to ask themselves that question. Between May of 1991 and July of 1993, four men, most of them customers of the city’s piano bars, turned up dead and mutilated, their bagged remains discarded in roadside garbage barrels. Investigators eventually traced the crimes to Richard Rogers, a nondescript nurse from Staten Island who, unbeknownst to his pickups, had the kind of résumé you never want in a hookup. In 1973, for example, he was acquitted of manslaughter in the bludgeoning death of his housemate at the University of Maine. He also had access to medical-grade sedatives, which he used in at least one episode, from 1988, to knock out a man whom he’d invited home. When the unlucky conquest awoke several hours later, “he was naked, lying on his back, and his hands and ankles were bound with more than a dozen hospital ID bracelets.”

Journalist Elon Green recounts Rogers’s crimes in Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York. Rather than focus on the killer—who has all the allure of a wet cocktail napkin—he foregrounds the lives and milieus of the victims. It’s a reparative act that doubles as an extended elegy for the decades of closeted or bullied queers who encountered similar demons in schoolyards, across dinner tables, in pews, or in the browser histories they desperately erased. “I became obsessed with the lives they wanted but couldn’t have,” Green writes of the men killed, and, by extension, other gay men forced into self-denial. “Here was a generation . . . for whom it was difficult to be visibly gay. To be visibly whole.” (Green, who identifies as straight, never explains why the victims obsessed him.)

Last Call is a salvage operation not only for individual lives, but for a whole bleak chapter of underground queer life. Green revisits the well-documented casual hysteria around AIDS, which was believed to drip “off the walls of the Tally-Ho Tavern” in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a county where one of the victims’ bodies was found. He recalls the “gay panic defense” that bewitched juries across the country during the height of the epidemic. But he also turns up evocative snapshots from byways such as Youngstown, Ohio, whose first gay bar opened in the 1950s. One local gay social club, quirkily named the Veterans of the Second War, had “sewn-together parachutes hung from the ceiling to mask the pipes.” My own favorite anecdote concerns a pianist in Philadelphia renowned for his acidic roasts of dead divas, including Karen Carpenter. The latter tune was “preceded by chants from the audience: Dig. Her. Up! Dig. Her. Up!”

(Such offbeat details compensate for Green’s smooth but bland prose. One image that will stay with me: during Rogers’s police interrogation after the murders, he began nervously farting.)

Philadelphia sets the stage for Green’s through line of antiqueer police action, or inaction in the case of homicide. In the 1950s, the city’s police commissioner (and future mayor) Frank Rizzo—a chunk of Brutalist architecture come to life and dipped in pomade—raided any establishment with a gay clientele. According to Green, the Humoresque Coffee Shop was raided twenty-five times over an eight-month stretch in 1958 and ’59. Tensions spilled into nearby Rittenhouse Square, where a custody battle over the seven-acre park played out between queers and straight families who just wanted to picnic among good Christians.

Things weren’t much rosier in New York. Activists there founded the Anti-Violence Project in 1980, partly in response to years of official cold-shoulder from police and judges. Green writes that “between 1985 and 1989, the number of antiqueer incidents reported by local groups increased from 2,042 to 7,031.” He also quotes a research paper from that era: “Seldom is a homosexual victim simply shot. He is more apt to be stabbed a dozen or more times, mutilated, and strangled.”

Although Green doesn’t reference it, he might have invoked the grisly killing spree in January of 1973 that left at least a half-dozen men dead in New York. One man’s body was found stabbed on a burning couch in his apartment; in another incident, two men—lovers or roommates—were also stabbed, and their pet poodle was drowned in the sink. As the New York Times reported, the Gay Activists Alliance accused the NYPD of “half-hearted interest” in the murders, and “said the police had imposed a blackout on information until the press picked up the story.” Years later, the movie Cruising dramatized a serial killer who preyed on leather bars, just as the 1973 murders seemingly targeted S-M aficionados. Nine months after the film premiered, a former cop with the NYC Transit Authority killed two men and wounded six others at the Ramrod bar in Greenwich Village.

Clearly, dead faggots have rarely been a civic priority. AIDS exacerbated the general apathy. By the time Richard Rogers showed up with his pilfered sedatives and his butcher kit (and his VHS collection of Golden Girls—another sticky detail), New York, all of America, was primed to shrug. Fortunately, the detectives from multiple jurisdictions who worked the case were dogged and had technology on their side. Rogers, now seventy, will almost certainly die in prison.

Last Call preserves the poignant irony that the trust and vulnerability that once made gay bars synonymous with gay community were also vectors of death, both in the form of murder and, later, HIV/AIDS. The same was true of New York’s piers and bathhouses. It’s traumatic enough when an outsider exploits and betrays that trust, but when it’s a member of the community like Rogers—or Andrew Cunanan, whose three-month murder spree in 1997 left five men dead, including fashion designer Gianni Versace, and who makes a cameo in the book—it’s akin to sacrilege.

Most true-crime writers favor the crime half of the equation. But there’s also the imperative of truth—not just the factual tally of names, dates, and numbers, but the existential question of why such horror happened at all. What confluence of circumstance and bad fortune brought these souls together in just this way? What combination of desire and courage flickered in one person, only to be snuffed by its perverted opposite in another? We never discover Rogers’s motive, if there was one. Maybe he was self-loathing. Maybe a synapse misfired somewhere in his brain, or a vital chemical evaporated. Green doesn’t know the answer, and probably Rogers doesn’t either. He declined to be interviewed for the book.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.