Blair McClendon

Blair McClendon

A new documentary by Alain Gomis reveals the quiet and disquieted complexities of Thelonious Monk.

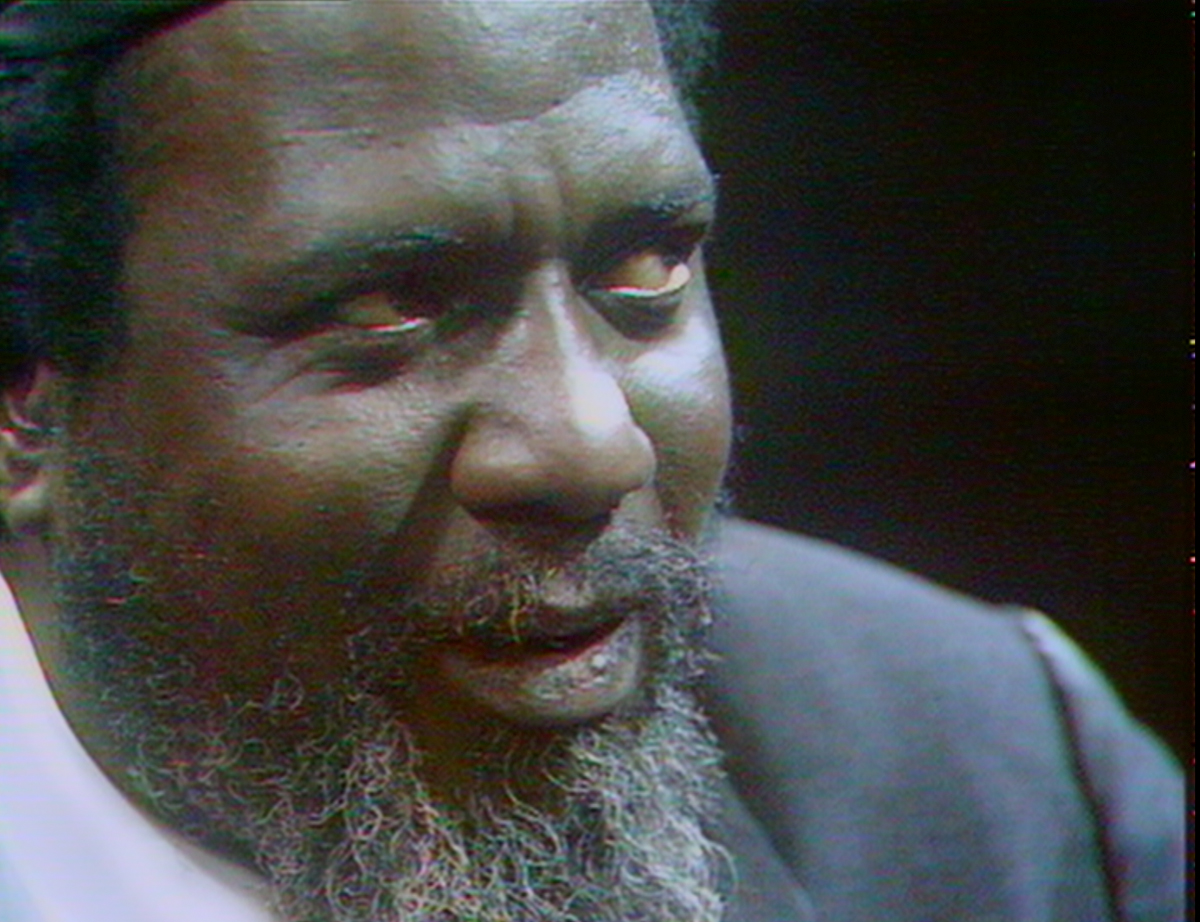

Thelonious Monk in Rewind & Play. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Rewind & Play, directed by Alain Gomis, Brooklyn Academy of Music,

30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, through March 16, 2023

• • •

For some of us it was Thelonious Monk, and not John Cage, who invented silence. His compositions and recordings are suffused with it. “Silence,” John Edgar Wideman once wrote, “a thick brogue anybody hears when Monk speaks the other tongues he’s mastered.” Monk developed the quiet until the songs implied everything that was not there. All of that preceded the quasi-mythical reticence to speak at length and his isolation during the last decade of his life, before his death in 1982. “Who said I retreated to silence?” Wideman has Monk ask. “Retreat hell. I was attacking in another direction.” It is a fitting fiction for a man who straddled the old guard and the New Thing in jazz, who stood apart from his peers even as he furnished them with countless standards, like “ ’Round Midnight.” Monk’s spare solo renditions of this track elucidate his vision most clearly, one where beauty is a hard-edged, mournful thing.

Thelonious Monk in Rewind & Play. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Alain Gomis’s new documentary, Rewind & Play, is a film about Monk’s face: its contortions, its ability to emanate pain, the sweat that comes off it in sheets while he plays, its look of earnest confusion when all he has brought to this world seems insufficient to quell a French interviewer who cannot hear how out of his depth he is. While researching the musician, Gomis received the archived rushes from his appearance on the television program Jazz Portrait: Thelonious Monk, recorded in Paris at the tail end of his 1969 European tour. At the time, in the waning years of his career, he was finally hailed as a genius, peppered with questions by the show’s host, Henri Renaud. The program was to have been the capstone for a triumphant return to Paris, where Monk first performed in 1954.

Music documentaries are hard to get right. They tend to be constructed around an archive of stunning performances, but, for reasons both stylistic and legal, a certain form has dominated: snippets of shows are interwoven with interviews attesting to the importance of what you are watching. Some of these films are brilliant, others rote, but either way they are forced to sidestep the power of their own material. All good musicians have something demonic about them, and when the best perform, they exhibit nothing less than spiritual possession. Every cut in a film risks severing that connection. With someone like Monk, the wrong cutaway could be disastrous.

Gomis is one of the few who could be trusted to assemble something so absorbing with this footage. His previous films, like 2017’s Félicité, share a similar sensibility with Rewind & Play, as though they were seeking to find a form at once logical and unsettled. Félicité, ostensibly a neorealist tale of a Kinshasa woman trying to find money for her son’s hospital stay, periodically erupts into song and flits away from the main story to follow its heroine on mysterious walks in the forest. He uses a searching approach in Rewind & Play, too, eschewing present-day interviews that might situate the viewer or attest to what is happening. Throughout, Gomis evinces a fascination with the gauzy, blue-tinted footage before him, interspersing technical aspects of Jazz Portrait (rollouts, 20khz tones) with snatches of conversation between the show’s producers—and in the process, shows not only a genius’s performance but also the work of crafting a public image.

Thelonious Monk in Rewind & Play. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

There are moments on the Jazz Portrait set and during footage shot at a bar when Monk looks disconnected. It is a worrisome sight, but perhaps even more so with some knowledge of the composer’s life: at the end of 1956, Monk was in a car accident and, looking lost and refusing to speak, was committed to Bellevue for several weeks. Rewind & Play balances these moments of disquiet with lengthy takes, showing him working his way through his compositions with singular purpose. These function like action sequences, Monk playing with such flat-fingered force it is a wonder the keys can bear it. Watching Monk play “Crepuscule with Nellie” in that Parisian studio is a good reminder that the piano is a hammer.

Robin D. G. Kelley wrote that “achieving the harmonic and rhythmic language recognized as Monk’s did not come easy to him—playing ‘straight’ was easier than playing ‘Monk.’ ” It should be an obvious point to anybody who has plinked at a piano and then listened to “Epistrophy,” but across its various incarnations, black art has been haunted by the double-edged sword of its supposed “expressiveness.” Its fans and detractors alike insist that they can feel the emotion even through the “mistakes” and lack of technique. But you don’t wake up one day feeling like Monk felt and turn out Brilliant Corners. First you spend years at a piano up against the kitchen wall, sweating just like he does in all the close-ups Gomis has found, and even then you would be lucky to have accomplished mere imitation.

Thelonious Monk in Rewind & Play. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Of the finished Jazz Portrait program, Kelley wrote that Monk appeared comfortable, that the camera “catches Thelonious smiling” and that he “knew he was being treated with respect.” Gomis’s film belies these assessments. In the rushes, Monk appears beleaguered, at times combative, resisting the pressure to satisfy Renaud. Jazz Portrait is not only about “his place in jazz history,” but was another attempt to shape the public understanding of the complex postwar relationship between black Americans and France. While France waged colonial wars, it characterized itself as the antidote to an America so racist it couldn’t help but run off its best writers and musicians. In one exchange, Renaud tries to guide his subject toward such a position. Monk explains that on his first trip to France, the audience’s hostility left him “ossified.” Renaud chides him, “No, no, don’t say this thing about that.” Monk looks around with some consternation: “It’s not secret, is it?” “No,” Renaud concedes, “but it’s not nice.” The pianist repeats those last three words, then flicks open his lighter and smokes. There is that quiet again, filling up the room.

Thelonious Monk in Rewind & Play. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

It is only the safe, the well, the untalented who desire to be tortured artists or mad geniuses, not knowing the costs of those identities. Monk gave us “ ’Round Midnight,” which has colored the collective dream of those desultory city nights that miraculously stay just this side of the kind that leave you feeling ravaged in the morning. Listen to him play it repeatedly on the takes for Thelonious Himself, where all its edge and bite, its silence, leap up to grab you by the throat, to make sure you really hear what comes next. Monk’s world was one of struggle, dogged by illness, deprivation, and misunderstanding. It has been easy to deploy him and his eccentricities like a plaything: he is a seer, bringing music from the heavens or the future, speaking in koans, one in a line of giants stretching back to Louis Armstrong. Satchmo blew and Satchmo grinned, and, without the dazzling glare of that smile, a whole music might never have slipped into the American idiom. Monk was as foundational, but he could never play the role. Gomis affords us time near him, near his work, and pulls off the raiments of an icon. Rewind & Play makes of Monk a man again, one who was gifted, loved, harassed. The tragedy of geniuses is not that they are otherworldly; it is that they are down here with the rest of us.

Blair McClendon is an editor, filmmaker, and writer. His film work has screened at Sundance, Cannes, Tribeca, TIFF, and other festivals around the world. His writing has been published in n+1, the New Republic, the New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere. He lives in New York.