Lake Micah

Lake Micah

In Margo Jefferson’s follow-up to Negroland, a memoir that dazzles at the intersection of intellect and artistry.

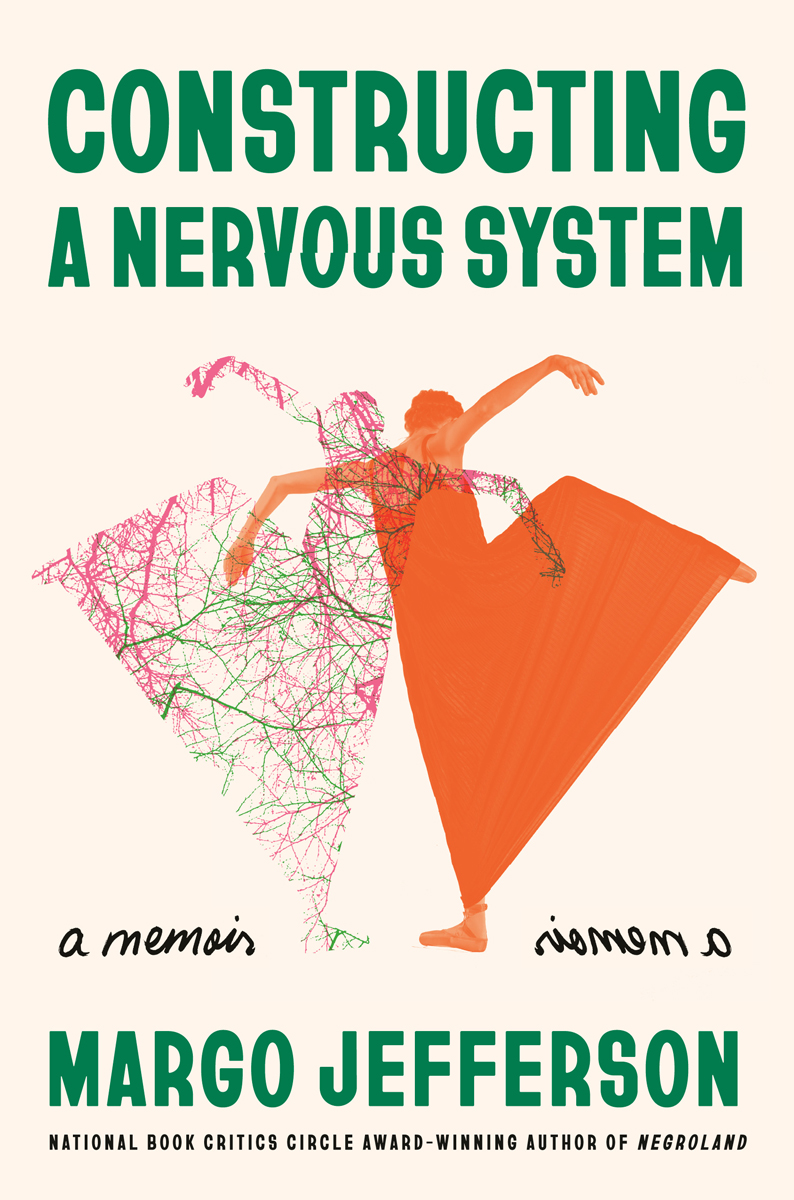

Constructing a Nervous System: A Memoir, by Margo Jefferson,

Pantheon Books, 197 pages, $27

• • •

The vintage and revenge of memory, its random lurch and rough stroke: this is her great theme, Margo Jefferson. The wounding recrudescence of past into present, the enduring melodrama of psychic disquiet—that thing necessary to resist and to contest, or else chance never to master, never to “domesticate”—are her immutable motifs. She prizes apart autobiography, splits it totally open; lunges audaciously at the delusions of the American demesne; flails and impales shibboleths; and she records her findings, the problematics of race and of class, in her trim, anamnestic albums. Her project, initiated with the diary Negroland (2015) and extended just now with Constructing a Nervous System, is to effect an inspection of a personal history that has become gloomed, stark: gothic, nearly; an expanse with the relict terrains of bygone traumas to traverse like a voyager through noesis, and recount with adventuresome élan.

The technique is that of estranging exposition followed upon by swift identification; the typical Jeffersonian scenario includes “those other kinds of racial shocks: ecstatic recognitions; sudden terror.” Her narration is solipsistic, almost—at once self-conscious and self-regarding. With the remit of anything that suits her fancy, she bears ideas not to their conclusion or completion but until she’s done with them. Cogitations flare fulgently upon the page . . . and are turned away from with the boredom, exasperation, ennui, and melodrama of whim. It’s a fractal composition, and proceeds by vaults (often somersaulting over the familial stuff of its predecessor, those things relegated now to the first and final pages) to land—where, exactly?

Now the arcade of memory is collapsed into one huge heap. Jefferson refuses chronology, neglects to date her reminiscences. The mode is memoir, but equally is it intellectual history, providing the genealogy of a sensibility passed down like a gene, or a gene disorder, and then spliced into another. “I wanted . . . to become an apparatus of mobile parts. Parts that fuse, burst, fracture, cluster, hurtle and drift.” This is maieutic and even existential work.

Experience itself is her métier. Jefferson is all the time affected, always securing impressions. These come from icons in the national mythos, artists of whatever stripe—Ella Fitzgerald, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Topsy. We see her pose like Mary at the Annunciation, receiving the epiphanies of an eidolon, or a sequence of them. As influences, these idols come to inform her dispositions, proclivities, instincts, affinities. Culture heroes of a sort, they march past in a brash and heterodox parade. “I craved imaginative compensations. License. I wanted to play in private with styles and personae deemed beyond my range.” Jefferson’s policy is one of radical imagination into and out of their predicaments, those beau ideals, their situations of alluring and historical specialty:

Willa Cather, I know something about your abjection, your compensatory drives, your erotic and emotional needs; how you made yourself into a vessel that could contain longing and rapture; desire never assuaged but never renounced. . . . Weren’t you as removed from that lyrical whiteness as I am? . . . Didn’t you risk being excluded from certain kinds of privilege and acceptance? . . . Surely all this drove you to imagine and interpret what had not imagined you. I’ve had to do the same.

Her intrepid self-stylings are traced and tracked, now with anxiety, now with sardonic authority, and finally with perhaps inevitable Du Boisian double consciousness. But this is a praxis wearied of the interminable scourge of race relations, those governing clichés whose negotiations await and ambush the black writer, hail her like a judicial summons. “Race is the modality in which class is lived,” said Stuart Hall; in the Jefferson oeuvre the truth of this is too tacit to allege. Here the dense immutability of racial fact—the chagrins and chills of identity—occasions much anguish and intrigue. Jefferson finds use for each. “I will turn these confounding dangers, these losses, into what I can manage: scenarios to follow; reactions to memorize and absorb; a workbook of behaviors. Preventive pedagogy. I will quash what’s unbearable.”

What is unbearable is the simulated experience and automatic living of life, as of late; “the Negro question”; the conversion of promised thrills to paltry accommodations; the pretenses and discomfiting ruse of liberalism; melancholia; the petrified and inert verities of our diffuse, disjunctive globe; the agon of race; the persistence of capitalist cupidity; what Adorno called “the totally administered world.” These must go.

Yet this remains Jefferson in her acquisitive mood, with an inclination toward “plundering—to access powers my upbringing denied me.” She takes in whatsoever is propitious to subsume, only that, to the omission of all the insalubrious rest; she wants for herself Ideas, collects them, adjoining them to her person with omnivorous concern. “I consume, I commandeer and stockpile these lines [of others]. They give me courage as I pursue dissonance, contradiction; fissures in and around this entity I call a self, a writer.” Her interest is in “remapping, resettling American culture. Devising new modes and manners.” So the dross and dreck in the culture industry must be barred, denied, defined against, but always substituted, offset, replaced and replenished with the eligible and personally adventitious. This makes for a different Margo Jefferson than that in Negroland, whose controlling schema was to pare, whittle, reduce, never intromit—in strenuous accordance with the stipulations of her black haut bourgeois milieu. Deny everything, deny the self, take on—in the painstaking mold of her patrician mother and physician father—nothing that might burden or impair: “It became necessary to take blunt weapons to whole parts of oneself and hack away.”

The dualism is familiar. A Barthesian strain presides over Constructing a Nervous System, guiding its careen and agile dialectical volution; we recognize at once the Roland Barthes of Roland Barthes, the aesthete whose precedent permits Jefferson to dither as she does, and to impede herself; cajole her subjects and quit them; be philosophically fitful, startling, treacherous, declamatory. “In one form . . . the aesthete is a willful exclusionist of taste, holding attitudes that make it possible to like, to be comfortable with, to give one’s assent to the smallest number of things . . . Elegance equals the largest amount of refusal.” This is the Jefferson of Negroland’s retrospect, the refiner contracting her preferences down to a point. (Though the quotation is from Sontag—in an essay on Barthes.) “In the other form, the aesthete sustains standards that make it possible to be pleased with the largest number of things; annexing new, unconventional, even illicit sources of pleasure. . . . Here elegance equals the wittiest acceptances.” This is Constructing a Nervous System, or what we might finally come to call Margo Jefferson by Margo Jefferson.

“My sensibility is a structure of recombinant thoughts, memories, feelings, sensations and words. It syncs concord and discord, trying not to simplify them. It lets gaps and distortions remain. I’ll decorate the available decorations. I’ll decorate the deprivations.” Heed the belletrism of the prose, the mandarin delectation of a major writer in her late style. As in Love’s Work, the masterwork by the late Gillian Rose, the text here is tissual, arch, an instance of autotheory if not of écriture féminine, too: the affidavit of a queenly doyenne of American letters. Circumstances pique and even pitch at a heady, expatiated frequency in this chronicle; remnants of pain and the tragical closure of affairs whirr and resonate. What else for Margo Jefferson to do but to mark the warp and weft of her world, her cosmogony of attitudes and of affects, writing for us a new form of Künstlerroman.

Lake Micah is a New York writer. He edits at Harper’s Magazine and the Drift.