Megan Milks

Megan Milks

In her new memoir, Lucy Sante finds gender euphoria.

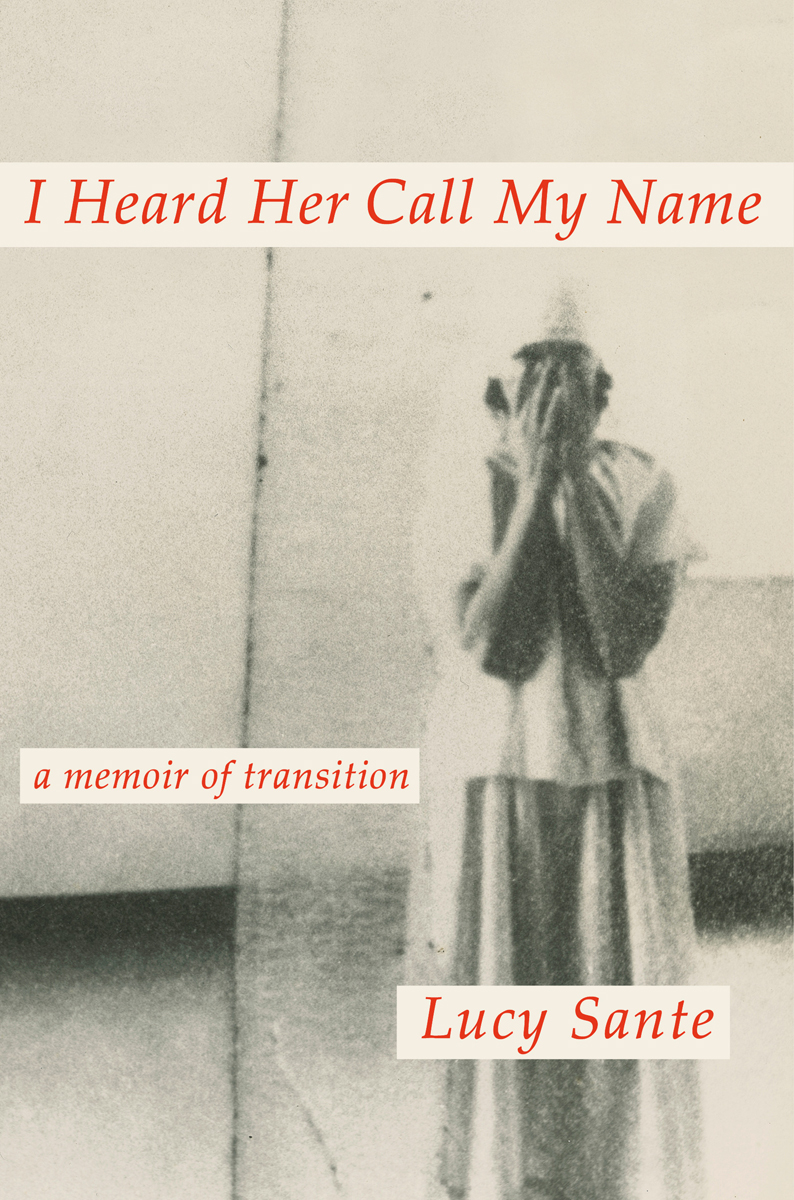

I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition, by Lucy Sante, Penguin Press, 226 pages, $27

• • •

Over the past decade or so, trans memoir has tended to fall into two categories. There’s the straightforward version penned by a newly out public figure—directed to a mainstream audience and organized around transition as a main event (or series of events). Then there’s the more self-consciously stylized work of personal nonfiction by a non-famous writer who is trans—who might engage with the form of the transition narrative but do so with a wink, a shrug, or a metaphorical or conceptual conceit (running, weather, jokes). This second category is in a vexed and critical relationship with the first, which does not give back, unaware that its enemy exists.

Lucy Sante’s new book, I Heard Her Call My Name, tilts toward the first (no surprise: see the subtitle), but in some ways bridges both categories. It’s a candid account of when, why, and how Sante chose to embark on gender transition at the age of sixty-six; yet one never forgets that she is a writer—a prolific critic, historian, artist, and scholar who has been honing her craft for decades. This is not the first record that Sante has shared of her life, and hardly the only one. What makes I Heard Her so compelling is how Sante uses this new trans lens to retell a life already told.

Sante was one of a few public figures who came out as trans during the first year or so of the COVID-19 pandemic—her February 2022 essay in Vanity Fair, “On Becoming Lucy Sante,” describes the sequence of events that kicked off the process, coincidentally not long after Elliott Page’s announcement. This memoir is an expansion of that piece, and tracks dual narratives. One begins with the coming-out letter she sent to close friends by email in February 2021, and chronicles the stages of her coming-out and transition since then. The other wanders her past from her birth in Belgium to adulthood, revisiting this life through a trans lens that gives it new meaning and perspective. “I managed to impersonate someone answering to my biographical specifics,” she writes of that period, characterizing it as one of self-doubt, social fear, and learned performance as a straight man and new American. Coming out in her sixties has entailed a painful confrontation with this former self but is an “enormous relief.” I Heard Her is a sustained and joyful exhale.

From I Heard Her Call My Name. Courtesy Lucy Sante.

The book wrangles with a central question: Why now? Why not sooner? “That is the riddle I can never quite explain well enough to my cis friends. How can my ‘egg’ have ‘cracked’ sixty-odd years after I first ‘knew’?” Sante briefly considers the role of the pandemic in her decision to transition. But the more direct link is the gender-swap feature on FaceApp. When Sante fed photos of herself into the app’s “magic gender portal” and saw herself transformed, the gong of trans certainty sounded. Days later, she came out to her therapist, then partner, son, and close friends. “The fortification of secrets I’d spent nearly sixty years building and reinforcing had crumbled to dust in a little over a week.” Wistfully presented as avatars of Sante’s alternate history as Lucy, many of these gender-switched photographs are scattered throughout the pages, creating a visual arc that ends with undoctored and radiant selfies.

Looking back, Sante draws illuminating parallels between trans and immigrant experience: “There was a distinct rhyme between gender transition and the sort of transitioning I’d had to do as an immigrant child becoming acculturated in the United States.” In the sections on her upbringing, I Heard Her returns to some of the material of Sante’s first memoir, Factory of Facts (1998), which focuses on the history of her birthplace, Verviers, Belgium. Reflecting on that strangely impersonal memoir in her second, she recognizes that she had “tried to absent myself” from the earlier book. “I didn’t want to be seen.” The contrast is stark: now Sante is giving readers selfies and candor. Almost immediately after coming out, she tells us, she became more social, marveling at the novel urge to call friends on the telephone. Adopting this same impulse toward intimacy, her narration gushes, reveals, confesses.

From I Heard Her Call My Name. Courtesy Lucy Sante.

Those who know Sante’s cultural criticism will delight in her accounts of New York in the late 1970s and ’80s, with figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jim Jarmusch, and Elizabeth Hardwick flitting in and out. She takes Sylvère Lotringer’s summer course in Paris, then a job in the mailroom at the New York Review of Books, where her literary career will begin. As always, her prose is elegant, nimble, and vivid, but here she gets more vulnerable: revisiting the East Village in the days of punk, heroin, and AIDS, she examines not only the “evidence” of her repressed desires during those eras but also (not unrelatedly) her evasions of transness. Mentioning her romantic involvement with Nan Goldin, Sante notes her avoidance of Nan’s roommate, the trans artist Greer Lankton. As a young employee at the Strand, she relegated trans-related pulp literature to the trash.

At times, Sante’s trans lens seems to click too easily into place over this long history—or maybe I’m just dubious of the urge to trawl one’s life for “proof” of transness (I say, having expended entirely too much energy on this project myself). But Sante takes care to situate herself and her experience of gender within her milieu, and makes no claims to the universal. She has come to understand transition as “a process of removal”: “so many things about my new being felt familiar, as if I were remembering them.” For her, the portal she has traversed is not between genders; it’s “the eye of the cognitive needle I had to pass through in order to break out of the prison of denial.” Insights like these feel fresh and singular; moments where she relies on more familiar expressions (like achieving “true selfhood”) feel less so.

And while I want to unreservedly bask in the glow of Sante’s gender euphoria, I can’t help but be disappointed when she sets herself apart from other trans people. She acknowledges some difficulty connecting with trans peers—but then, with the exception of a confident younger trans friend, she often distances herself from them, and even describes some trans women uncharitably (users on Reddit trans forums are “mutton [dressed] up as lamb”). The aforementioned younger friend “unrolled for me the panorama of the trans literary scene,” she shares, “which I had not known existed.” One gets the sense that Sante did some cramming. Her turn to a communal trans “we” at the end seems shaky—a different kind of learned performance.

Yet, despite those reservations, what comes through most powerfully is unfettered self. Having wrenched off the “cangue” of masculinity, Sante has flourished—and relaxed. “Often, in varied circumstances,” she writes, “I experience a kind of serenity, a general rightness with the world, an acceptance of my being.” In I Heard Her, Sante writes from this space of serenity. The warm, companionate narrator Sante has let loose is the book’s most moving achievement. It’s a beautiful clarity of self to be invited into, and Sante’s is a remarkable life to see anew, through this rush of intimacy and wonder.

Megan Milks is the author of the novel Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body, finalist for a 2022 Lambda Literary Award, and Slug and Other Stories, both published by Feminist Press.