Megan Milks

Megan Milks

A new book by artist Lana Lin drawing from Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas digs into the Asian understory

of Stein’s and Toklas’s writings.

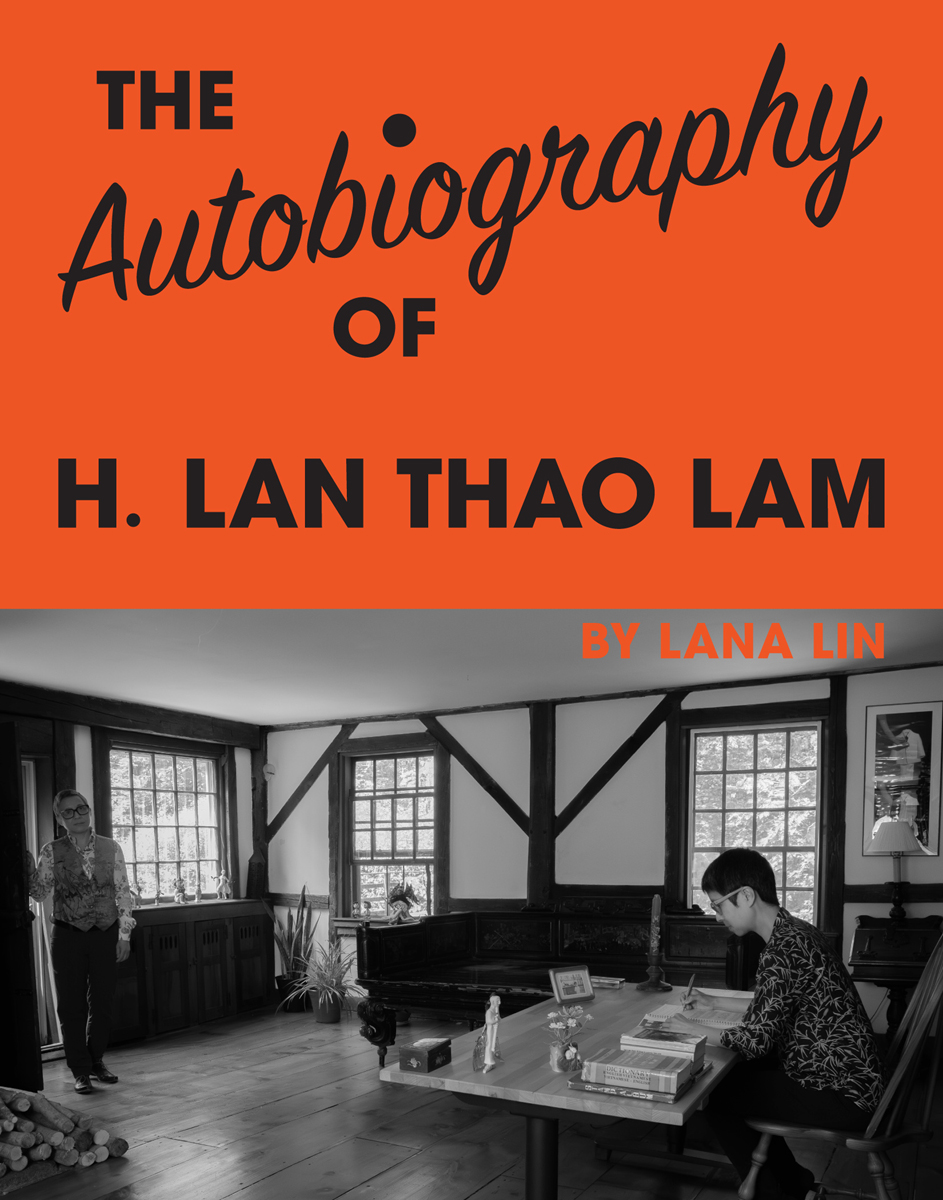

The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam, by Lana Lin, Dorothy, a publishing project, 217 pages, $18

• • •

At a slight five feet, two inches, the interdisciplinary artist Lana Lin once speculated in a journal entry that she might just be small enough to fit inside another person. It’s an uncanny image—and an apt metaphor for what Lin is up to in The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam (her second book, after the scholarly monograph Freud’s Jaw). Here, Lin steps into the interiority of her partner, H. Lan Thao Lam, ostensibly to narrate, as Lam, Lam’s life. That for much of the book the central subject is not in fact Lam themself but rather Lana Lin might seem paradoxical were it not obvious that Lin is also inhabiting Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933). In the source text, Stein adopts the perspective of her partner Alice, whose gaze is trained devotedly back onto Stein. Zipped into the bones of this tricksy classic, Lin’s ingenious and absorbingly tender book meditates on dyadic identity while honoring the miracle and the mundaneness of bonded life.

Lin and Lam have long been publicly entangled. Romantic partners for two and a half decades, they have developed a significant oeuvre as the duo Lin + Lam—working with archives, interviews, and found objects to make multidisciplinary art, often with a feminist and postcolonial lens. Both have also continued to create individually, and Lin is most known as an experimental filmmaker. Though The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam can perhaps be read as an extension of their collaborative practice, it’s decidedly Lin’s project, and maintains her ongoing fascination with intertextuality. (Her film The Cancer Journals Revisited, for example, closely engages with Audre Lorde’s groundbreaking illness memoir.)

Like Stein and Toklas (who met in Paris), Lin and Lam (who met in New York) are queer life partners who found home with each other in a city, and a nation, that was not their first. Lin’s version tracks her and Lan Thao’s shared life and artistic development in New York in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, a period bookended by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. In many ways, Lin’s book closely follows Stein’s, lifting the structure and reorienting it around Lana and Lan Thao—the chapter “Gertrude Stein in Paris, 1903–1907,” for example, becomes “Lana Lin in New York, 1988–1999”—and directly borrowing some of its language. Both commemorate the twenty-five-year history of their subjects’ joined lives. And both cheekily flick at the boundaries between biography and autobiography, memoir and fiction, self and other, life and art.

All that said, these are also very different endeavors. Where Stein’s is a bombastic who’s-who of the Parisian cultural milieu she helped create with her weekly salons, Lin’s is quieter, albeit more explicitly “out” as a love story—and she gives somewhat more level footing to the partner she’s inhabiting. Even while presented as having narrative control, Stein’s Alice comes across as auxiliary, her primary duty in life to witness and certify her partner’s genius. Lin’s Autobiography gives Lam more presence and (eventually) more space—devoting a later chapter to Lam’s childhood during the Vietnam War and their family’s escape from Sài Gòn to a refugee camp on the Malaysian coast.

One impetus for the book, Lan Thao tells us, was to bring “the understory to the surface.” From the first pages, Lin highlights the Vietnamese servants and Chinese refugees who show up in the margins of Stein’s and Toklas’s writings. Referencing Monique Truong’s novel The Book of Salt (2003), which imagines the life of one of Stein and Toklas’s Vietnamese cooks, Lan Thao notes, “And this is how I know that my people cooked for Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein; we neither hosted nor were invited to dinner.” Lin’s emphasis on unearthing the Asian and Asian American understory—that which undergirds not just the source text, but also history, politics, city infrastructure—guides much of her book’s associational logic.

The main plot slips back and forth in time and place to trace Lana and Lan Thao’s lives together: from their meet-cute in New York to their most intense argument to date (“the sock incident”) in Hà Nội, from Lan Thao injecting an immune cell booster into Lana’s thigh post-chemo to mornings spent observing the great blue heron that graces the pond of their home in Connecticut. In addition to Stein and Toklas, Lin draws parallels to other intertwined dyads, such as Eve Sedgwick and her friend Michael Lynch, Emily Dickinson’s Nobody and implied Somebody, and E.T. and Elliott from the film E.T. Lan Thao describes the moment that E.T. taps his beloved with his glowing finger as a kind of impregnation that enables Elliott to carry E.T. within him. “Indeed we can find ET within ElliotT, just as Lana can be found within Lan Thao,” they observe, referring to the enclosure of the word “Lana” in “Lan Thao.” “I carry Lana within me and in turn I expand her. Like the collectivity of sea turtles, like Elliott-E.T., Lana and I are at our best as ‘we.’ ”

What could be more desirable—and more terrifying—than this kind of fusion? I think of Jessica Gross’s new novel, Open Wide, in which the narrator discovers she can actually zip open her lover and enter his body, with disastrous consequences. Or the Pandrogyne project Genesis P-Orridge coauthored with he/r partner Lady Jaye, a series of surgical body modifications designed to enact a complete merger. Is this . . . love? But the voice that Lin has constructed in her Autobiography comes across not as troubling so much as knowing, bemused by its own wiles. “There have been times when, with pleasure, Lana and I experience ourselves as fused together,” Lan Thao narrates, “but the pleasure in this is in seeing each other and ourselves, seeing each other in ourselves, and not in being seen by others as each other. In fact, it is not being seen as separate entities by others that breaks the spell.”

There’s an irony here—because although Lana and Lan Thao maintain a separateness as characters, Lan Thao’s constructed voice is always already fused. In this sense, the book seems to flip inside-out and outside-in, like a reversible bucket hat or someone manically tapping the 180-degree pivot function on Facetime. As a reader, I found myself pleasurably disoriented and looking for tells—that is, for Lana Lin slipping off the veil of the fictional autobiography with details that only she, and not Lan Thao, could know. But there are no such details. It is not unthinkable that Lan Thao could reconstruct what Lana Lin (the character) thought and felt at any given moment; it is not unthinkable that Lin (the writer) could construct Lan Thao’s thoughts and feelings from what she knows of them. Though Lan Thao is our constant guide, the point of view is a canny and winking performance of braided intimacy. Who’s inside whom? Lin delivers a delightful entanglement that glows with shared light.

Megan Milks is the author of the novel Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body, finalist for a 2022 Lambda Literary Award, and Slug and Other Stories, both published by Feminist Press.