Bob Nickas

Bob Nickas

From CIA plots to Hitler’s living brain: an exhibition looks back at

art and conspiracy.

Wayne Gonzales, Peach Oswald, 2001 (left) and Dallas Police 36398, 1999 (right). Installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy, the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York City, through January 6, 2019

• • •

A presidential assassin, possibly, Lee Harvey Oswald, and his assassin, certainly, Jack Ruby. Elevator doors part and there they stand, side by side, in art as in life, in life after death, welcoming visitors to the Met Breuer show. These portraits by Wayne Gonzales are central to his investigation of history painting that began in the late ’90s, his own “Death and Disaster” series, focused—as if through a rifle scope—on the killing of JFK on November 22, 1963. The date may serve as the point from which a clear notion of conspiracy theory began to take hold in popular consciousness, spreading into pop culture and wider use, a term meant to undermine speculation beyond official findings as: crazy, paranoid, lacking credibility. The term is conspiratorial in itself.

From the Latin conspirare, conspiracy means “to breathe together.” This definition looms atop the reproduction of an Andy Warhol Electric Chair on a poster announcing an exhibition to benefit the legal defense fund for the Chicago Seven, accused of inciting a riot during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The Youth International Party (aka the Yippies) initially beckoned “rebels, youth spirits, rock minstrels, truth seekers, peacock freaks, poets, barricade jumpers, dancers, lovers and artists” to the convention, demanding “the politics of ecstasy.” The protests began peacefully; it was later revealed that the violence that erupted had been provoked by undercover police. Warhol’s source photo was the electric chair in which Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed, having been convicted of espionage in 1953.

Emory Douglas, covers for The Black Panther, 1969–74. Installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Conspiracy Means to Breathe Together poster is included neither in the exhibition, Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy, nor in its catalog. But it echoed in my mind as I toured the show, resounding for us now, with the rights of free speech, free assembly, a free press, and democracy coming under increasing attack. Preying on all sorts of fears, whether from inside, outside, left or right in a decentered terrain, conspiracy is available to all. Nowadays, however, the perpetrators cry foul. Of the more calculating conspiracy theorists at work, one lurches about 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. As I write this, his cronies have invoked “a vast left-wing conspiracy” to derail a Supreme Court nominee. Yes, everything is connected, and today we all breathe the same scarefied air.

Alfredo Jaar, Searching for K (detail), 1984. Offset lithographs and inkjet print. Image courtesy the artist.

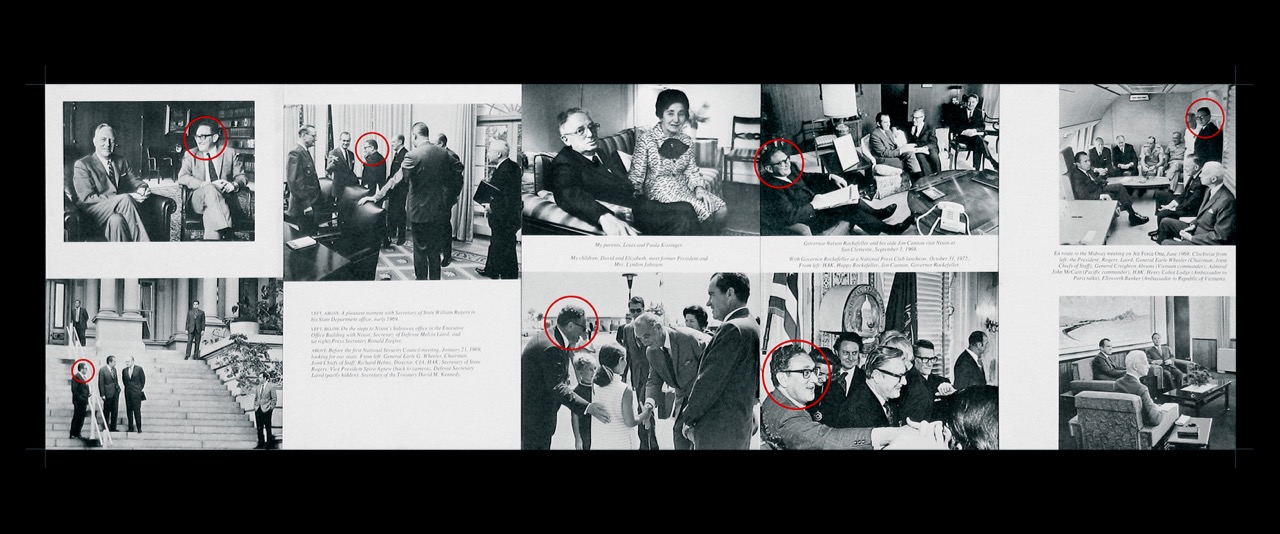

Curators Doug Eklund and Ian Alteveer do not make their exhibition a show trial of current events, choosing instead to explore the specters and plots of the past, which handily indict a nightmarish present. Days before the opening, a member of Pussy Riot was mysteriously poisoned following a Moscow court appearance. Is it 2018 or 1818? History defeats itself. Time stands still. At the Met Breuer, the FBI and the CIA shadow numerous works on view, from those of Emory Douglas (published in the Black Panther newspaper), Alfredo Jaar (on the trail of Kissinger and Salvador Allende’s overthrow in the artist’s native Chile), and Öyvind Fahlström (World Map, 1972, charting economic exploitation and repression), to those of Trevor Paglen (“black sites” of secret detention), Sarah Anne Johnson (covert mind-control experiments with LSD), and Sue Williams (All Roads Lead to Langley, 2016).

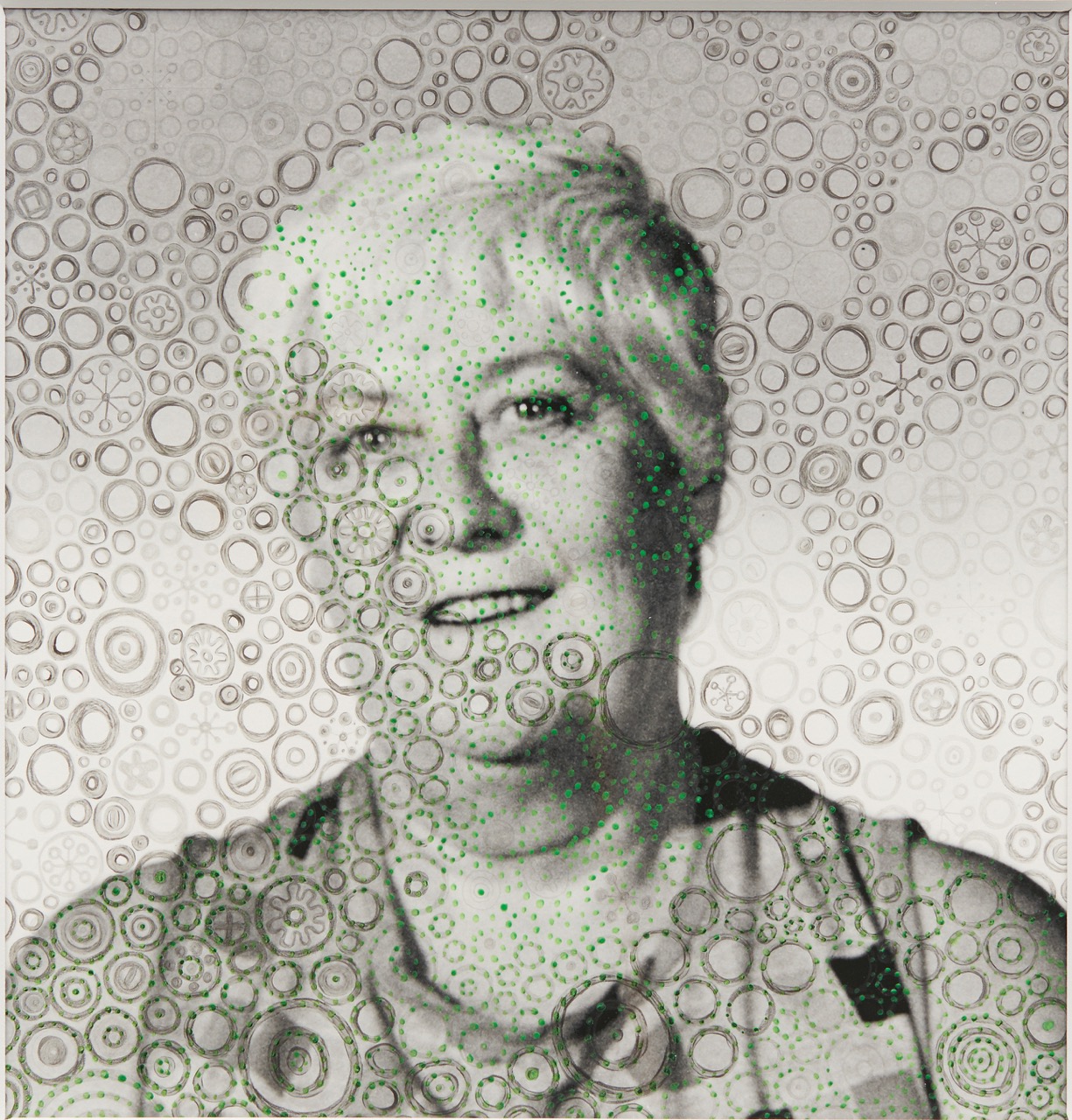

Sarah Anne Johnson, Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, 2008. Graphite on inkjet print. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

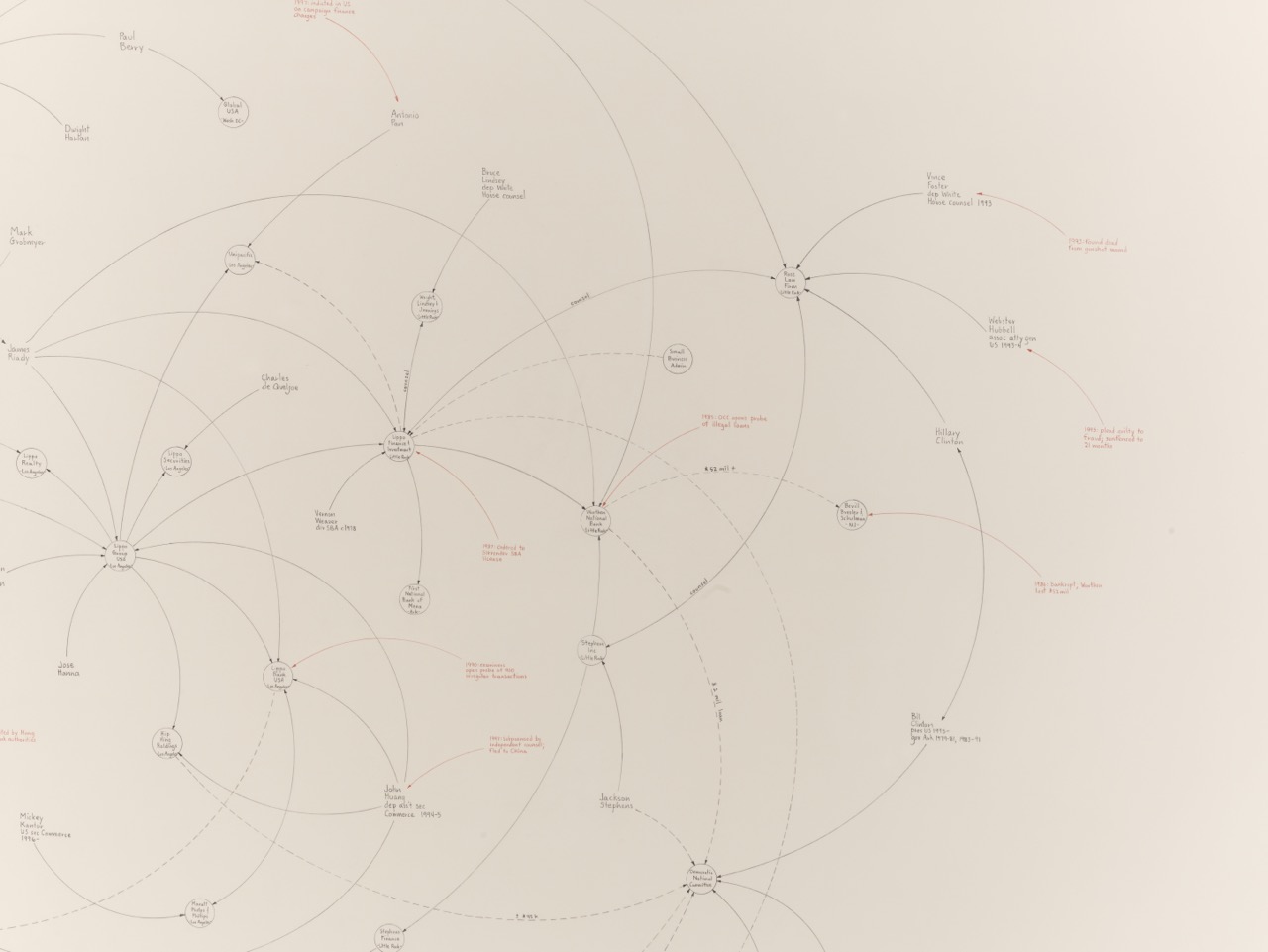

The artist as investigative journalist is often encountered, Mark Lombardi prominently—himself the subject of conspiracy theories after his early death in 2000. In one key work he traces an intricate web of foreign funds used to influence a US election. (Sound familiar?) A predecessor, also on view, is Hans Haacke’s Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 (1971), revealing widespread corruption in one of New York’s largest holding companies. The work, along with a related piece of Haacke’s, led to the cancellation of his Guggenheim exhibition that year, and its curator’s subsequent termination. (If governing systems avail themselves of censorial privilege, why not museums?) While both artists engage documentary modes, Lombardi’s heightened visual display renders corruption celestial: money rains down as if from Heaven above. A 2007–09 work by Alessandro Balteo-Yazbeck and Media Farzin revolves around the reproduction of a prank invitation to a 1939 opening at “The Museum of Standard Oil” that resulted in the firing of a MoMA staff member.

Mark Lombardi, Bill Clinton, the Lippo Group, and Jackson Stephens of Little Rock, Arkansas (5th version), 1999. Graphite and colored pencil on paper. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

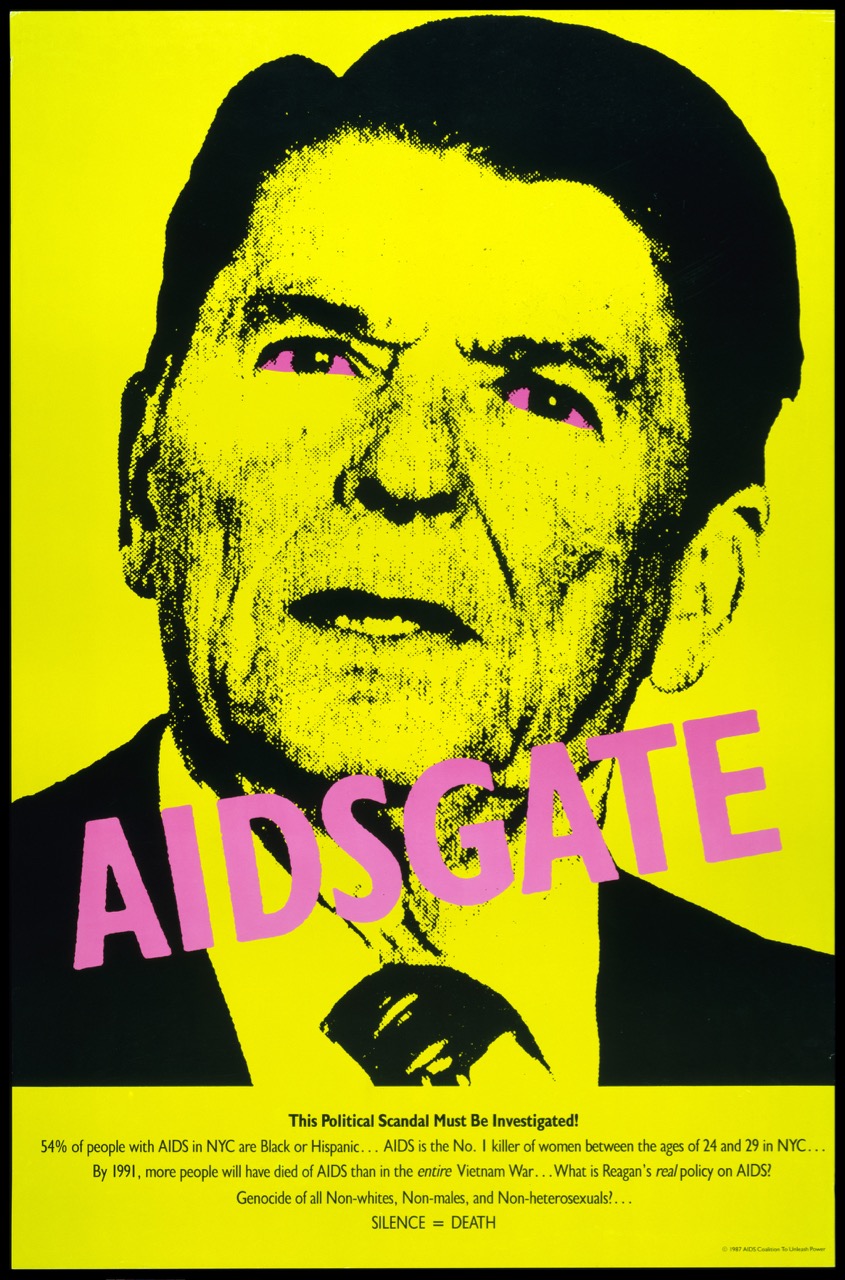

Once-provocative artworks such as these suggest that a show about conspiracy is only possible since the ’80s, a period when institutions faced renewed criticism from a generation of artists, critics, and curators whose lessons came from those opposing the system twenty years prior. A confluence of art and politics in outraged response to Reaganism and the AIDS crisis raised levels of disaffection not witnessed since the turbulent civil rights and Vietnam eras. Ultimately, every generation wonders: How far have we really come? Is the situation any better, especially for artists perennially excluded? At the heart of perceived injustice and its potentially conspiratorial roots is the imperative “Question Everything,” which inevitably elicits pushback. Activism in the ’80s met with resistance in the decade that followed—the politically contrived culture wars of the 1990s led by conservatives, with morality as their crucible. (If you can’t win one battle, fight another.) Many of the artists in Art and Conspiracy, having gone through those times, well aware of how museums were held accountable in the ’60s/’70s, might have been canvassed at the opening: Nowadays, don’t museums appropriate the meaning of everything they show? Is there anything they can’t absorb? Haven’t the institutional critique artists gone on to become museum darlings? Many of the works in this exhibition are from museum collections, including the Met’s own. The once inconvenient art and agitprop of the past is today safely cocooned. It’s the proximity of the present that alarms.

Silence = Death Project, AIDSGATE, 1987. Lithograph. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The curators have pointedly acknowledged that the show arose from remarks made by the late Mike Kelley in a 1991 interview with fellow artist John Miller (here represented by a “Game Show” painting that creepily suggests Wheel of Misfortune). Kelley observed: “I don’t think that there’s anybody in the academic world who will even go near conspiracy theory at this point. Once it starts to become obvious how it is a motivating factor in real life, then people will start to write about it as a mythology or an ideology.” If that happens, Kelley felt, “we’ll really learn something about our society.”

Cady Noland, Untitled (Vince Foster), 1994. Installation view. Image courtesy Ringier Collection.

And what have we learned since Kelley made these remarks? In the passing of a quarter century, truths revealed will be denied—and from the top down. After all, who complains loudest about fake news? Overdue and right on time, this is a show Kelley would have thoroughly enjoyed, particularly for its mix of cartoonish forensics (Peter Saul’s 2006 Untitled, subtitled Hitler’s Brain Is Alive), darker undertow (Cady Noland’s inversion of the flag-draped coffin of Vince Foster, White House deputy council in the Clinton administration, an apparent suicide), and pre–X Files whimsy (Jim Shaw’s The End Is Here, 1978, with its “proof that JFK was KILLED by Aliens”). These works brought us full circle, back to that unnerving portrait of Oswald, eyes upturned to meet our own, following us every step of the way. Out on the street, taking a deep conspiratorial breath alongside a spectral Mike Kelley, we imagined an appropriate public coda: Infowars’ Alex Jones hung in effigy, upside down, dangling from a lamppost on Madison Ave.

Bob Nickas is a writer and curator based in New York. He has organized well over one hundred exhibitions and artists’ projects. On October 4, at Kerry Schuss, he opened Strange Attractors: The Anthology of Interplanetary Folk Art, Vol. 2, The Rings of Saturn. His most recent collection, Komplaint Dept., was just published by Karma.