Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Two volumes of the late critic and curator’s writings provide a crucial orienting point from which to expand the horizons of contemporary art.

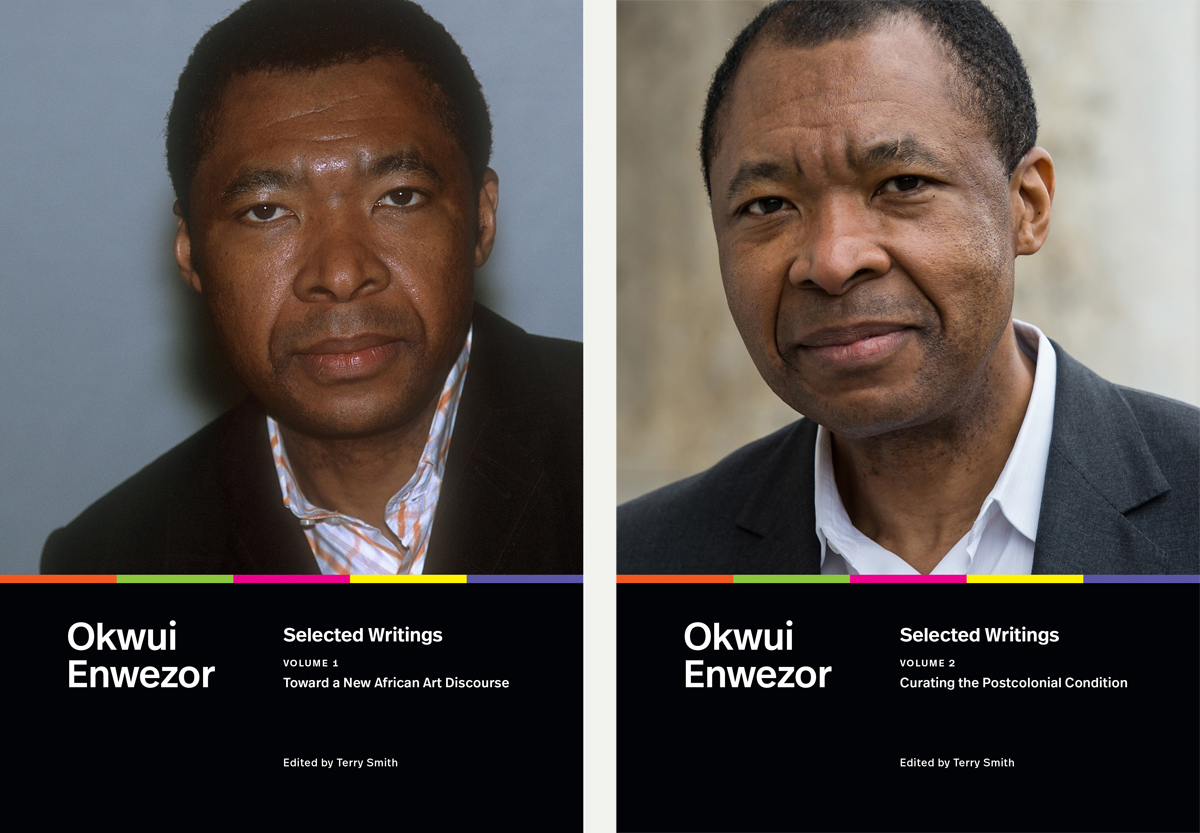

Okwui Enwezor: Selected Writings, Volume 1: Toward a New African Art Discourse and Volume 2: Curating the Postcolonial Condition, edited by Terry Smith, Duke University Press, 444 pages and

528 pages respectively, $40 each

• • •

There is a moment on the one-hundred-twenty-third page of Okwui Enwezor: Selected Writings, Volume One where it is exceptionally clear how committed Enwezor was to language. In a piece entitled “A Question of Place: Revisions, Reassessments, Diaspora” (1997), he argues for the role of the diasporic literary imagination in the formation of African subjectivities. While describing the work of poet Tchicaya U Tam’si, Enwezor observes:

He is a poet of silences, of the discrete moment, the oblique public laughter, the discontinuous. His work moves in avid declensions and explores the most obscure places (public and private) without any obstructive flourish to investigate the lugubrious, lonely, existential geographies where the immigrant African subject whiles away his time dreaming of the homeland and return. U Tam’si’s imagery evokes the glazy atmosphere of detachment which speaks to the absurdity of diasporic metropolitan life.

On the level of the sentence, Enwezor was undoubtedly expressive. His sense of literary ambition manifests with each phrase—configured to build propulsive momentum, anchoring and attuning the reader’s ear in the process. Here, he deftly marshals the potency of form to attest to the substance of subjective experience. Through literary analysis posing as catalog essay, we meet Okwui Enwezor: a writer and a poet.

Such moments appear often throughout this formidable set of Enwezor’s texts, edited by Terry Smith in collaboration with advisors Salah M. Hassan and Chika Okeke-Agulu. Comprising thirty-two pieces published from 1994 to 2020, the two volumes are named Toward a New African Art Discourse and Curating the Postcolonial Condition, respectively. Together, they demonstrate how, at the threshold of the twenty-first century, Enwezor sustained a resolute intellectual project: to underscore the undeniable agency of those historically relegated to the position of object within Western regimes of socioeconomic, geopolitical, and discursive power. His was an unapologetic agenda—to change who and what was seen at the center of things.

For Enwezor, the curatorial process was enmeshed in the act of writing. He possessed a rare sensibility that emerged both in space and on the page. In this way, his essays function less as afterthoughts to his exhibitions and more as intermedial accompaniments, providing opportunities for deep thinking, granular consideration, and lively debate. As such, the merits of uniting his extensive written output are substantial. By reading across discrete texts, projects, and decades, one can discern how his specific ideas bloomed; how they were reinforced and expanded or deconstructed and reexamined; and how they were ultimately enlivened anew.

For example, through tracts such as “Travel Notes: Living, Working, and Traveling in a Restless World” (1997) and “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994” (2001), one can perceive Enwezor’s early interest in destabilizing normative geographic vantage points and modes of periodization, laying fertile terrain for his essay “The Judgment of Art: Postwar and Artistic Worldliness” (2016). That these writings accompanied two blockbuster shows and one historic biennial affirms Enwezor’s commitment to the exhibition as a discursive form, not a museological one.

Over the arc of his career, Enwezor critically engaged with various terms that now constitute the lingua franca of contemporary art discourse. He disenchanted “internationalism” and excavated the “global” for all it was worth. Because of him, words like “postwar” and “contemporary” cannot live as benign categories for artistic production, social identification, or historical periodization. Instead, they function as pressure points—triggering a critical consideration of the politics of representation within histories of artistic production.

Enwezor’s contributions to the history of African photography are particularly profound. Whether through his consideration of studio portraiture in Mali and Senegal or his examination of photography’s vexed position within South Africa’s apartheid era, Enwezor maintained a consistent proximity to the medium throughout his career. As a result, he made enduring contributions to the global turn in the history of photography by affirming the role of the medium in the story of African modernity. Yet, across these two volumes, he deploys various means through which to surface this argument. As Smith perceptively notes in his introduction, “Enwezor traces photography as a performative practice, as an archive of social and personal memories, as a theater of sexualities, and as a precipitating medium for moving-image installations that explore these potentials.”

While maintaining a fundamental investment in the African continent, Enwezor’s mind was porous and peripatetic. An avid traveler and omnivorous imbiber of culture, he was also a voracious reader, engaging the likes of Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, and Hannah Arendt alongside Edward Said, V. Y. Mudimbe, and Édouard Glissant. In his works, the tactics of a political writer reveal themselves in the cadence of a poet. Look no further than Enwezor’s interpretation of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida in “Archive Fever: Photography between History and the Monument” (2008) to understand his investment in the application of critical theory toward aesthetic analysis and societal diagnosis. However, Enwezor’s lack of substantive engagement with black feminist theorists such as Sylvia Wynter, Hortense Spillers, Saidiya Hartman, and Denise Ferreira da Silva dates him. His discussion of Afro-pessimism in “Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography” (2006) is also notable in its anticipation of Kevin Ochieng Okoth’s critical orientation toward the term, rather than positions shared by Jared Sexton and Frank B. Wilderson III. Blackness is not a monolith, and neither are its theoretical formations.

Alongside Enwezor’s intellectual progressions, this set tracks his professional ascent. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, Enwezor was no longer an upstart disruptor. He had swiftly become a powerful protagonist occupying a central position in contemporary art’s international infrastructures. Yet, he remained consistent in his literary sensibilities and ever sensitive to the violent workings of power. Take this passage in “The State of Things” (2015):

It is as if the entire global society—from the smallest hamlet to the most massive megacity—exists in the long, interminable insomnia of rulers, and the endless days of vigil kept by protesters and citizens. Sordid governmentalities and shredded social relations keep rulers and the ruled on a permanent state of alert, a form of wakefulness that tortures the imagination, numbs the mind, scars the body. In this realm of dissolution the global landscape is jittery with apparitions. Images appear and recede. Language becomes guttural, turns to stone; while in the burgeoning art system contemporary art turns cold in a repose of formalist rigor mortis.

In this discussion, Enwezor portends our current conjuncture with eerie precision. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the workings of the attention economy and market forces continue to cannibalize critical discourse, while the resurgence of so-called strongman politics and virulent censorship underscore the stakes of civic engagement, personal health, and collective action. As I reread his incisive 2006 analysis of Kevin Carter’s harrowing picture of a crumpled, famine-stricken child being stalked by a vulture, I was struck by the morbid parallel to the emaciated bodies of children in Gaza and Sudan that flood the posters, newspaper spreads, and digital screens of my daily life. Indeed, as Enwezor notes, “the world we inhabit today makes no pretense toward any idea of coherence or settledness. It is one of constant upheaval, redefinition, and change.”

In her foreword, Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi states that Enwezor “inspired curatorial models that abandon the nation and its ideology as a condition of human experience and its expression, emphasizing instead experiences of hybridity, multimodality, and creolization.” Indeed, Enwezor’s fiercest critics faulted him for serving as a “culture broker” who elided the politics of border crossing for those with African passports and consolidated capital, prestige, and power for artists living in the diaspora. For such critics, this was achieved at the expense of cultivating a thriving art discourse for those living and working on the African continent, ultimately ossifying an image of Africa seen from Europe and North America (where Enwezor resided for most of his adult life). Yet, these volumes demonstrate the continued utility of examining Enwezor’s positions—not only for what he engendered, but for what he provoked.

In this context, Enwezor’s contributions might be set in productive tension with his Francophone contemporaries, such as Simon Njami and the editorial collective Revue Noire, as well as curators living and working in Africa who positioned institution-building at the core of their curatorial practices. Take Bisi Silva (1962–2019), who curated the most important edition of the Rencontres de Bamako (2015) and whose Centre for Contemporary Art Lagos is home not only to a significant reference library but also a roving pedagogical program, Àsìkò, which convenes interdisciplinary cohorts of artists, critics, and curators in intensive workshops across the African continent. Then there is Koyo Kouoh (1967–2025), who curated an incandescent edition of Limerick’s EVA International, had a strong hand in multiple editions of the Dak’Art Biennial and documenta, and founded RAW Material Company in Dakar—a platform for art, knowledge, and society. At the time of her death earlier this year, Kouoh had been appointed the artistic director of the sixty-first Venice Biennale.

My own intellectual formation was directly informed by Enwezor, Kouoh, and Silva. I belong to the last generation of curators whose lives and careers have been personally enriched by these figures—directly benefitting from their various projects while witnessing how they occupied space, commanded rooms, and ignited imaginations through conversation. These figures were monumental not only in their output, but in their fierce sense of self-determination, staunch commitment to artistic experimentation, and technical prowess in the realpolitik of shifting historical narratives.

Books such as Okwui Enwezor: Selected Writings are a boon to future generations, making it impossible to forget or erase the foundational work that has been done. In a world ever antagonistic to the potential of African autonomy, it presents a rich set of primary texts for critically minded artists, critics, curators, and scholars. These tomes enrich and expand the disciplinary horizons of contemporary art, curatorial studies, the arts of Africa and the African diaspora, global art infrastructures, critical theory, and the history of photography—re-enlivening increasingly closed circuits of twenty-first century discourse with the bombastic fervor of our most recent century’s turn. These are crucial orienting points for those who remain committed to decolonial modes of contingency, entanglement, and rupture in the face of revisionist canonical narratives.

Selected Writings exposes a self-conscious writer’s orientation to the unfolding of sociopolitical events in tandem with creative expression. For Enwezor, telling time—or, rather, thinking historically in the present—was a way to discern the means through which sets of relations could be jostled and deconstructed, whether intimate or geopolitical, hegemonic or collaborative. That he was able to achieve this in only twenty-five years of professional work is frankly astounding. As Hassan and Okeke-Agulu argue in their prefatory note, Enwezor paved the way “more than any other curator and critic, in reordering not just the landscape of contemporary art but also the ways we talk and write about it. The clarity and tenacity of his vision [was] remarkable, compelling, urgent, and necessary.”

By the time of his death in 2019 at the age of fifty-five, Enwezor had taken the Nuyorican Poets Café by storm, cofounded the academic publication Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, and visited hundreds of artists’ studios across the globe. He had served as dean of the San Francisco Art Institute (2005–09), adjunct curator at the International Center for Photography in New York (2005–11), and director of Munich’s Haus der Kunst (2011–19). His editions of the second Johannesburg Biennale (1997), documenta11 (2002), and the fifty-sixth Venice Biennale (2015) had irrevocably shifted the terms through which art is viewed and discussed. All the while, as these vital volumes reveal, he wrote compulsively and relentlessly. In short: the man was prolific.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is the Peter Schub Curator of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. She holds a PhD in Art History from Columbia University.