Michelle Orange

Michelle Orange

A documentary on the “Nazi directress” by Andres Veiel raises new questions about art, ethics, and judgment.

Leni Riefenstahl during the CBC interview “Leni Riefenstahl in her own words,” 1965. Courtesy Kino Lorber. © CBC.

Riefenstahl, directed by Andres Veiel, now playing in theaters in New York City, opens September 12, 2025 in Los Angeles

• • •

In her 1975 essay about the German actress and filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, Susan Sontag described the “insinuative” mechanism by which liberal societies rehabilitate figures of public infamy, especially if they are artists. In Sontag’s formulation, the churning of our “cultural wheel” had, in this instance, not just cleared but rendered irrelevant the ethical stink trailing a director whose greatest works are also the most potent examples of Nazi propaganda ever made. One need only wait “for cycles of taste to distill out the controversy” in order to once again enjoy, unbridled and pure of aesthetic conscience, Riefenstahl’s most famous films: Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938), which respectively make of Adolf Hitler’s 1934 National Socialist Party Congress at Nuremberg and the 1936 Berlin Olympics two works of mammoth, quasi-documentary, fascist spectacle. The wheel Sontag invokes would appear to turn one way only, although the essay in question, “Fascinating Fascism,” marks a reversal of her argument ten years earlier, in another essay, “On Style,” that Riefenstahl’s “genius” affords the director “a sublime neutrality”; that the “complex movements of intelligence and grace and sensuousness” of her twin masterpieces relegate both the content of the films and the intention with which they were made to “a purely formal role.”

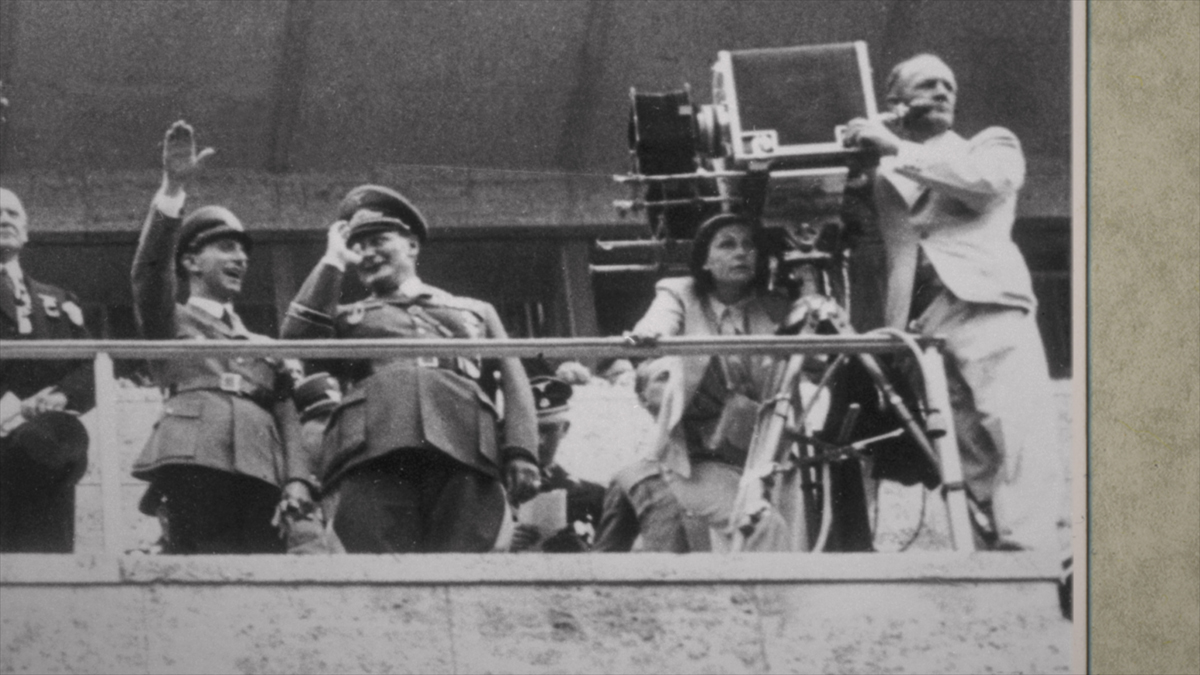

Leni Riefenstahl at the camera, during the shooting of Olympia, with Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring to her right, 1936. Courtesy Kino Lorber. © Vincent Productions.

An openness to paradox, if not outright contradiction, may be a kind of litmus test for higher forms of engagement with Riefenstahl and the dire seductions of her oeuvre. A landmark in this regard, The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl, Ray Müller’s 1993 epic, cubist portrait of its then-eighty-nine-year-old subject, offers a study of, among other things, that subject’s refractions and consuming will to subterfuge. Made with Riefenstahl’s participation, the three-hour film soon abandons its opening gambit, in which a narrator wonders aloud whether this “legend with many faces” should be considered “a feminist pioneer, or a woman of evil?” Instead, Müller probes the near-complete abstraction of self that has presumably helped usher Hitler’s favorite propagandist into a startlingly vigorous, determinedly public-facing old age. In more ways than one, it becomes clear, the striding, girlish, preening, prickly Riefenstahl’s survival has depended on both repeatedly fielding and leaving unanswered and unanswerable the question of her responsibilities—as an artist, a citizen, and a human being. In the film’s closing moments, Riefenstahl responds to Müller’s suggestion that a reunified German public now expects from her an apology, an admission of guilt, by segueing from a practiced expression of regret to an insistence that she was never anti-Semitic, nor a member of the Nazi party. “So, what am I guilty of?” she asks, with a mix of defiance and chilling sincerity. “Where does my guilt lie?”

Materials from the private estate of Leni Riefenstahl. Courtesy Kino Lorber. © Vincent Productions.

With Riefenstahl, in some ways an addendum to Müller’s film, German director Andres Veiel offers, foremost, a few pointed ideas on that front. It was access to Riefenstahl’s personal archives—seven hundred boxes of materials and several dozen hours of recordings—in the wake of the 2016 death of her longtime partner, Horst Kettner, that persuaded Veiel there might be more to say. Or settle: Riefenstahl is full of gotcha moments. A clip of Riefenstahl insisting that Triumph of the Will bore no racist sentiment is followed by one from that film in which a speaker implores his audience to hold dear its racial purity. Unreleased footage from Wonderful Horrible Life shows Riefenstahl becoming apoplectic when Müller confronts her with Third Reich Chancellor Joseph Goebbels’s diary account of their cozy social ties. We hear her chuckling, in a 1978 conversation with her publisher, over her recollection of being told, as a young star of the mountaineering films that first made her famous, that her physical form—blond, strapping yet feminine, with fine features and a long, sensuous mouth—was a fascist’s wet dream. We read her fawning missives to Herr Hitler, whose persona she has acknowledged she found overwhelming (hearing him speak for the first time, she was “captured, as if by a magnetic force”), but of whose political agenda and systematic annihilation of six million people she long claimed ignorance. “The film’s impact as German propaganda is much greater than I could have imagined,” she wrote of the release of Olympia, a month after Hitler’s 1938 annexation of Austria and seven months before Kristallnacht. “And your image, my Führer, is always applauded.”

Contact sheet from the holdings of Heinrich Hoffmann, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek / Bildarchiv: Leni Riefenstahl welcomes Adolf Hitler in her villa in Berlin-Dahlem, 1937. Courtesy Kino Lorber. © Bayerische Staatsbibliothek / Bildarchiv.

The marquee discovery here is a letter, written in 1952 by an adjutant to Riefenstahl’s then ex-husband, a former Nazi officer, describing a report that details Riefenstahl’s inadvertent involvement in the massacre of twenty-two Jews in the early days of the 1939 invasion of Poland, which she had agreed to document for the Nazi regime. Needless to say, this account differs substantially from Riefenstahl’s own. Plenty of the filmmaker’s signature self-pity and prevarication is on display here, redolent now as ever of the many uses of doublespeak, the rhetorical loopholes whose applications today range from gaslighting your girlfriend to hog-tying a democracy. Veiel makes note of the fact that, in drafts of the memoir she spent over a decade writing and rewriting, accounts of the same event often vary, “almost as if she needs to make sure herself.”

Leni Riefenstahl checks her appearance for the recording of the three-part documentary Speer und Er, directed by Heinrich Breloer, 1999. Courtesy Kino Lorber. © Bavaria Media.

The word “shame” appears within a handwritten passage of those drafts, where Riefenstahl describes her rape as a young virgin—a story she tells the same way each time. Accounts of similar assaults follow, including one perpetrated by Goebbels. In an interview this spring, Veiel described the difficulty he had situating material involving the violent abuse Riefenstahl suffered at the hands of her father, lest she appear too sympathetic, or any causal connections be made. In this, Riefenstahl is reflective mainly of that great cultural wheel’s latest turn: a wish for definitive, straightforward judgment of an artist whose fascist ties and aesthetic influence have acquired new resonance. But the case against Leni Riefenstahl, “Nazi directress,” as Veiel has called her, has been locked down for generations, as evidenced by this documentary’s array of public indictments dating back to the early 1950s. More pressing, perhaps, is an equally ardent case for how things could not have been otherwise, even for a woman of her sensibility, vision, and drive.

There is an inconvenient truth to Riefenstahl’s protest that a majority of Germans in the 1930s felt as she did: desperate for their humiliations, singular and collective, to come to an end; spellbound by a fantasy of command and submission, of personal agency and ecstatic, communal surrender, of the supremacy of beauty and subsummations of a beautiful death. The context Riefenstahl insisted upon, across decades spent trying to puzzle together a viable edit of her own story, is also what condemns her. A paradox that bears further examination, if we are to make any more sense of Riefenstahl’s wonderful horrible life, and work, than she was able to do.

Michelle Orange is the author, most recently, of Pure Flame: A Legacy.