Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

The past is female: a debut novel imagines deliciously embodied desire among sapphic modernist icons.

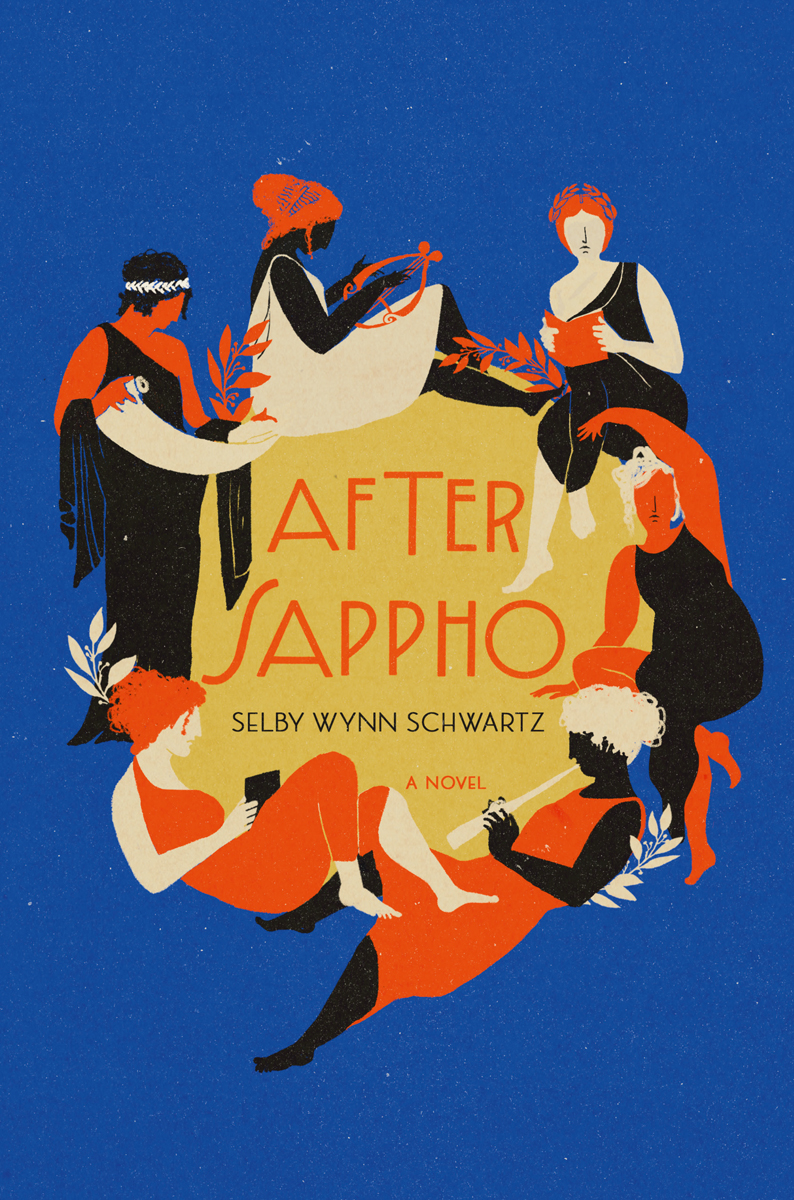

After Sappho, by Selby Wynn Schwartz, Liveright, 272 pages, $28.95

• • •

The past is one of the great spaces for the erotic imagination, an endless source, not only for settings and costumes, but for true stories about love. And every love story is a history, a tale of recognition: the eye caught, the gaze returned, oneself seen reflected in the other’s existence. The history of women yearning for women is a thread of sex and knowledge, running from Sappho of Lesbos down the ages.

Yet if recorded lesbian history begins with Sappho, its opening chapter is full of empty spaces. A few complete poems and many broken lines are what is left to us of Sappho’s songs. Some translators have guessed at the absent words while others have emphasized the lacunae in her texts, the impossibility of reconstructing her phrases from crumbling papyri. In Anne Carson’s bilingual edition, If not, Winter (2002), she translated the poet’s known work, finding beauty in the incompleteness of fragment 42, “their heart grew cold / they let their wings down,” or the tantalizing 24C, which reads merely: “we live / . . . the opposite / . . . daring.”

Inspired by Carson’s improvisations, Selby Wynn Schwartz’s debut novel, After Sappho, is a playful exegesis of, homage to, or riff on this incomplete miscellany of love. Journeying through history and literature, Schwartz’s Booker-longlisted text brings sapphists, poets, performers, and activists from the modernist period into poetic relationship with each other. In the centuries since Sappho, lesbians have often been portrayed as enigmatic, forgotten, or “apparitional,” Terry Castle’s word for their ghostly manifestations in European literature. Schwartz, on the contrary, makes the case for the presence, in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century, of a deliciously embodied female—sometimes straight, often gay—desire. Dancer Isadora Duncan, Parisian nightclub owner Ada Bricktop Smith, the actresses Sarah Bernhard and Eleonora Duse meet up in her pages, make pilgrimages to Lesbos, write letters, encounter writers in salons and activists at feminist gatherings. Italian feminist Sibilla Aleramo falls in love with Duse when she sees her in A Doll’s House. Duse goes to Italy’s capital for the 1914 International Congress of Women, where she learns about women’s rights from Ukrainian-Italian firebrand Anna Kuliscioff. “It is more difficult than you think to work from life,” Romaine Brooks sighs, while her lover, heiress Natalie Barney, remarks to Aleramo that there is no need to journey to Rome, for women can have congress in Paris, too.

These modern women “longed for writing tables that were not in the kitchen, stained with onions; we wanted to read the novels kept from us because they were decadent and suggestive; we wanted to exchange the finger-pricked linens of our trousseaus for travel guides and foreign grammars. . . . In our letters, we murmured the fragments of our desires to each other, breaking the lines in our impatience. We were going to be Sappho, but how did Sappho begin to become herself?” writes Schwartz, who uses Sappho’s words and phrases as recurring motifs. Aithussomenon is one, a feeling like the trembling of light on leaves. For Schwartz this trembling can be anticipatory, romantic, or safe, like Barney’s Paris home, where she “made a haven from fragments, a garden where sunlight could set the leaves quivering.”

The rules of language become another source of inspired play. The genitive case, she writes, is often “defined as possession, as if the only way one noun could be with another were to own it, greedily. But in fact there is also the genitive of remembering, where one noun is always thinking of another, refusing to forget her.” Remembering is the case of the poet, who “lies down in the shade of the future and drowses among its roots.” Miss Janet Case appears, too, in her role of Greek tutor to Virginia Woolf. The genitive of possession can be a struggle for the shy lesbian, while the genitive of remembering is that practiced by Orlando, right up until Orlando is published in 1928, the same year that Woolf gives a lecture, “Women and Fiction,” in which Chloe likes Olivia.

“Chloe liked Olivia” is Woolf’s famous challenge to writers to fill the blank pages of female friendship. Those pages, of course, have been well filled since then, and to read After Sappho in the context of fifty years or so of feminist and lesbian documentation is to wonder, despite all its pleasures, why it is necessary to keep circling around a few iconic figures, Natalie and Virginia and Vita Sackville-West and Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall. “Where are the expatriate salonnières, / the gym teacher, the math-department head? / Do nieces follow where their odd aunts led?” Marilyn Hacker asked four decades ago in her witty history lesson “The Ballad of Ladies Lost and Found,” answering her own question with a queer female lineage that is considerably more diverse than Schwartz’s Eurocentric one.

Along with traversing ground that is so well documented (most recently in Diana Souhami’s No Modernism Without Lesbians, her fine 2020 group biography of Barney, Bryher, Gertrude Stein, and Sylvia Beach), I question Schwartz’s choice to narrate much of the book in the first-person plural, the “we” of a Greek chorus. “We” can be an exhilarating invitation to collective action, but it can also be a barrier. Who is doing the work of shaping that “we”? Who does “we” leave out?

On the other hand, the prose in After Sappho is seductively beautiful and wears its erudition with style. (Schwartz, who has a PhD in comparative literature, appends a satisfying note on sources to this “hybrid of imaginaries and intimate nonfictions.”) Turning to address her readers in the final lines, Schwartz invites them (us?) to “try writing the story of Chloe and Olivia yourselves. The first thing is to change their names, so that the story will feel like your own.” And it is surely true that there have been many Chloes who have liked an Olivia, in many senses of “like,” and who have told that story, in fiction or biography, letters or messages, crying on a shoulder or laughing on the phone.

Julie Phillips’s most recent book is The Baby on the Fire Escape, on mothering and creative work.