Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

Marriage, motherhood, menopause, masturbation, and a motel: a new novel by Miranda July.

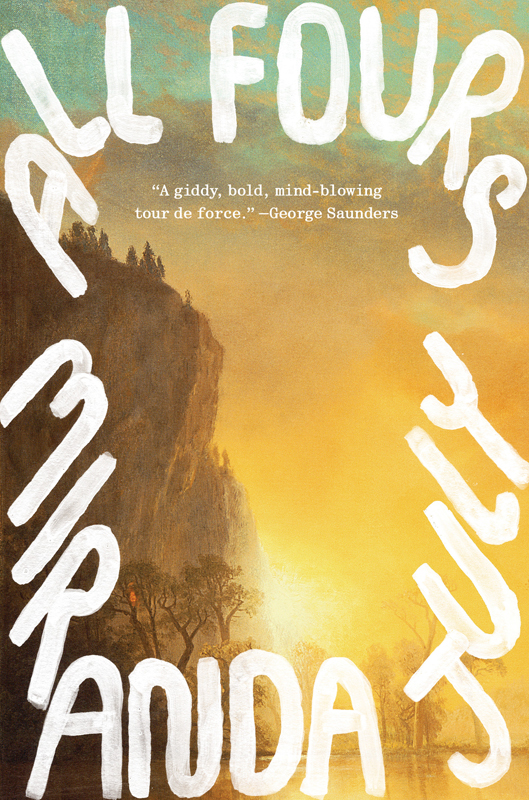

All Fours, by Miranda July, Riverhead, 326 pages, $29

• • •

Waifish and awkward, actress, filmmaker, and writer Miranda July wields an innocent persona whose cute, inappropriate curiosity leads to razor-sharp insight. All Fours, her first novel in nearly a decade, follows a moderately famous artist who works intuitively, intensely, with fierce discipline, feeling that she’s “perpetually at a crucial turning point; everything is forever about to be revealed.” But she’s also, in her mid-forties, mired in marriage and motherhood and feeling her age. Manic pixie dream girl menopause? What to do?

In All Fours, which is as close to autofiction as July has come, the starting point is the unnamed narrator’s conflict between the urgency of her work and the daily deflation of returning to her husband and their seven-year-old. Her parenthood in particular traps her in societal expectations: “Without a child I could dance across the sexism of my era, whereas becoming a mother shoved my face right down into it. . . . It came from everywhere. Even walking around my own house I felt haunted, fluish with guilt about every single thing I did or didn’t do.” Instead of refusing the burden of guilt, she uncomfortably evades it, concentrating on “turning the wheel of the household,” while keeping “most of myself neatly contained off-site.”

Her husband, seeing her frustration, suggests she take a three-week car trip from her home in Los Angeles to New York. So All Fours, after a false start as a sort of thriller (in which a possible voyeur takes pictures in front of her house), gets underway as a road novel. Then it changes gears again: less than a day into her carefully planned trip, the narrator exits the freeway and checks into a motel. On impulse, she decides to stay, phoning her husband with imaginary updates from Utah and Indiana while she spends the money for her trip on new curtains, carpet, and tiles to transform room 321 into a private paradise.

The rented room as space for a middle-aged woman to regain herself has a history in fiction, from Doris Lessing’s moody, enigmatic The Summer Before the Dark to Francesca Lia Block’s bright, wistful Necklace of Kisses. But All Fours doesn’t stick with this metaphor either: instead, the narrator plunges into an erotic obsession with a man named Davey, a boyish thirty-one-year-old with Huckleberry Finn good looks who works for a local car rental agency.

The narrator doesn’t understand why she’s doing this, at first, and that’s fine with her:

There did not have to be an answer to the question why; everything important started out mysterious and this mystery was like a great sea you had to be brave enough to cross. How many times had I turned back at the first ripple of self-doubt? You had to withstand a profound sense of wrongness if you ever wanted to get somewhere new. So far each thing I had done . . . was guided by a version of me that had never been in charge before. . . . My more seasoned parts just had to be patient, hold their tongues—their many and sharp tongues—and give this new girl a chance.

This new person is overcome with unexpected longings and is frank about the wayward nature of midlife desires, sexual and otherwise. But in letting her pursue the “wrongness,” July creates problems for the novel. For one thing, the narrator’s infatuation with Davey—which has sweet and comic moments but is described in tiresome detail—feels like a wish fulfillment fantasy for the author, undercutting the characters’ reality and the novel’s emotional stakes. Besides, though there’s nothing better than a love story, one-sided love is a bore. That’s why there are limits to how much you want to hear about your best friend’s crush, and why even maternal devotion, with its unequal nature, can be as dull to witness as it is overwhelming to experience.

For another thing, this “new girl” isn’t a girl; she’s a woman in her forties who’s just been hit between the eyes by time. Sex must be the answer, she thinks, or masturbation, or at least working out to make her ass look better, like a polyamorous Bridget Jones. She’s a free spirit, she feels, and “a person with a journeying, experimental soul should be living a life that allowed for it.” That’s great, but honestly, if the narrator were a middle-aged man, this statement would be a cliché the size of a barn. All Fours engages with some original and necessary ideas: about how sexual pleasure has the power to restore a person’s sense of self, about the erotic as a life force (see Audre Lorde), about mothers’ sensual selves and how they can reclaim bodies and emotions that have been colonized by their children. But the narrator also toys with individual solutions (multiple partners) to structural problems (maternal guilt) and acts out fantasies of clinging to youth in middle age.

Just as solipsism can be a pitfall of romantic obsession, the motherhood memoir risks losing its way, narratively and thematically, in the weeds and brambles of daily life. There’s some harrowing marital drama in the novel, and plenty of hot sex, but there’s also a lot of ordinary complaining about menopause and motherhood, the kind of domestic griping that acknowledges bad situations but undermines the will to change them. None of it is anything less than brilliantly written, but All Fours arrives at a deeper level of feeling only near the end. Only then does the narrator drop her ingenue persona and admit her dread, longing, and, especially, the mind-altering emotional scars left by the birth of her child, who came into the world eight weeks early and only minutes from death.

The problem of adulthood, for the narrator, is not just how to keep one’s options open. It’s also that to have a family is to be burdened with the knowledge of mortality. It’s here that the book is strongest, and that July is bravest—because confronting the body’s transience, in life and art, and learning to live with it, is a hard task, more terrifying and more generative even than freedom.

Julie Phillips’s most recent book is The Baby on the Fire Escape, on mothering and creative work.