Nick Pinkerton

Nick Pinkerton

The art of solitude: reexploring Luis Buñuel’s take on Defoe.

Image courtesy Leopardo Filmes.

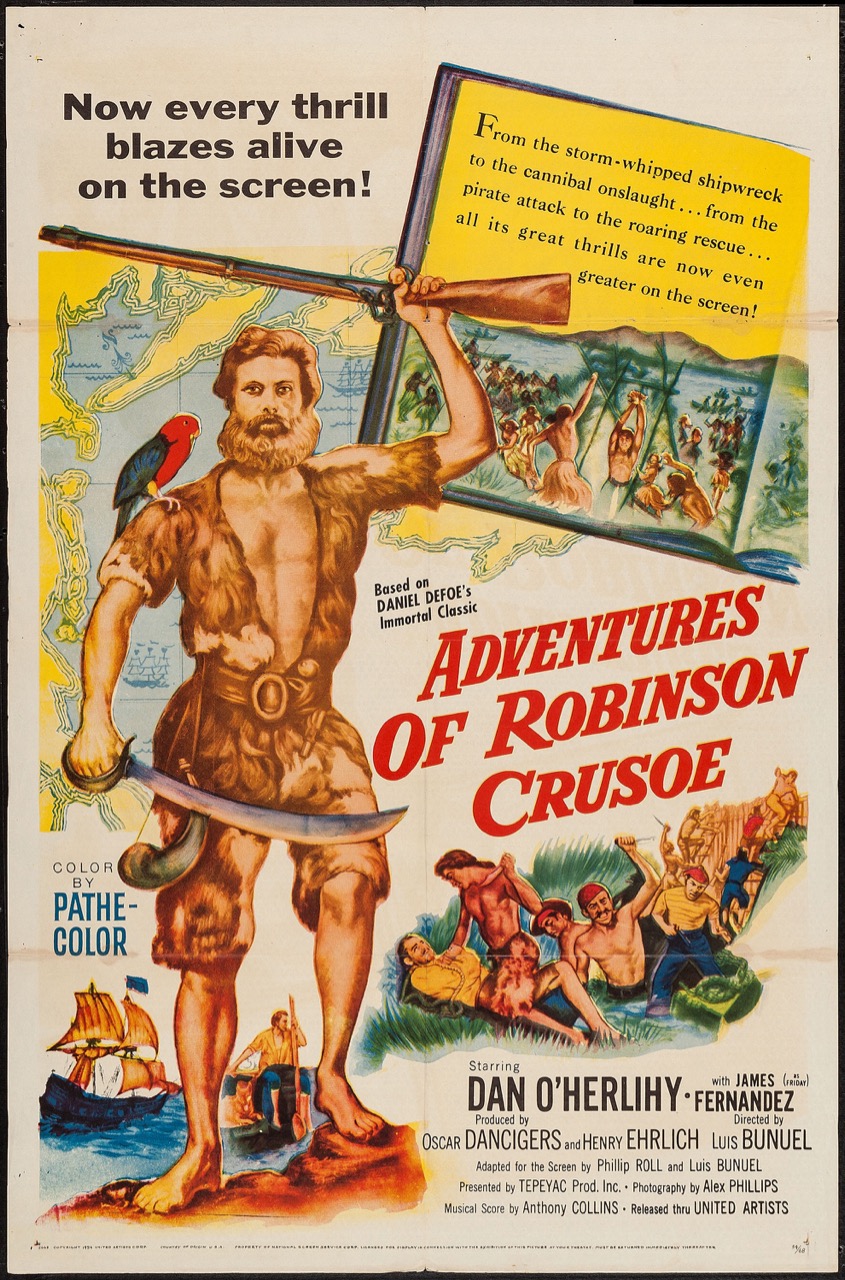

Robinson Crusoe, directed by Luis Buñuel, available to rent on

Amazon Prime Video

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

I don’t have numbers from the various streaming services to prove it, but as weekends melt into workdays and the very months begin to blur together, I wouldn’t be surprised if there has been a sharp uptick of interest in the films of Luis Buñuel. For those itchily passing the time with company, there are The Exterminating Angel (1962) and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), with their inescapable locked-groove dinner parties; for those in solitary confinement, Simon of the Desert (1965), an apostate’s telling of the life of Saint Simeon Stylites, the fifth-century Syrian ascetic who lived for forty-seven years alone on the top of a series of pillars in the desert outside Aleppo.

A perverse predilection for stories of humanity in extreme isolation is plain from the early years of Buñuel’s work, as evidenced in his 1933 pseudo-documentary on the inhabitants of an impoverished, unapproachable mountain village, Land Without Bread. Another remote land, where bread is to be got only with much sweat from the brow, is the setting of a Buñuel picture little-seen today: his 1954 adaptation of Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe’s 1719 account of a shipwrecked man’s exile, and one of the foundational fictional texts of the art of solitude.

If Robinson Crusoe, which garnered an Academy Award nomination for Irish actor Dan O’Herlihy’s lead performance, is given short shrift in discussions of Buñuel’s work, this may owe something to its outlier status. It’s Buñuel’s first film in color and, as with his 1956 hell-is-other-people jungle slog Death in the Garden, has a lushness unknown in his color films made in temperate-weather climes. Shot by the Mexican-Canadian cinematographer Alex Phillips—who, alongside Gabriel Figueroa, was the presiding photographic genius of the Mexican Época de Oro cinema—Robinson Crusoe is at times savagely beautiful, as when Crusoe screams himself raw in the direction of a tropical sunset, his torch dropping into the surf a potent image of snuffed-out faith. Robinson Crusoe is also Buñuel’s first film in English, one of only two in the language—the other, 1960’s The Young One, was likewise cowritten with the blacklisted Hugo Butler, and likewise the story of a stranger on an out-of-the-way island, this one in the coastal Carolinas.

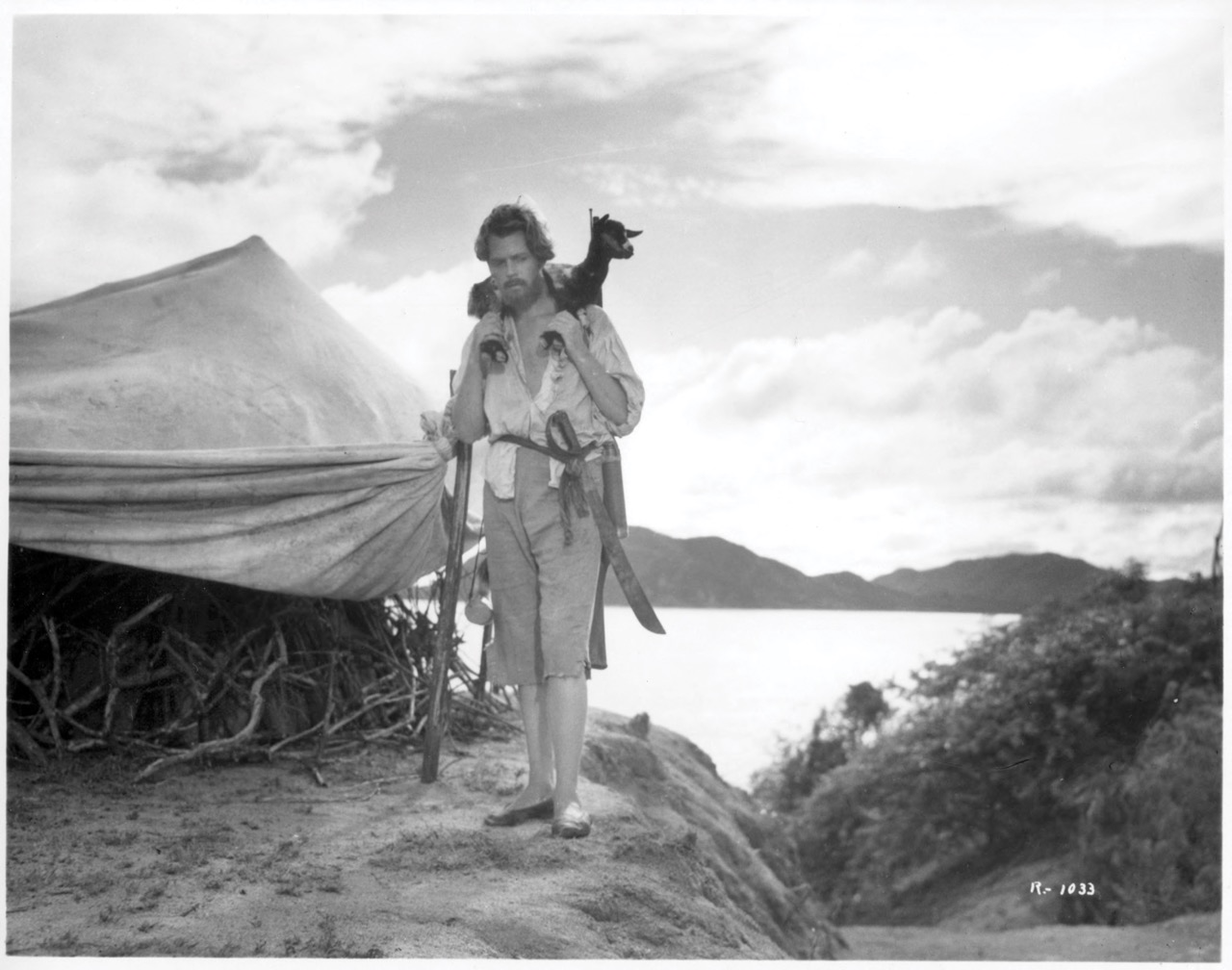

Dan O’Herlihy as Robinson Crusoe in Robinson Crusoe (production photo). Image courtesy Leopardo Filmes.

Pairing the voices of Defoe, whose hero survives by practice of the continence and punctiliousness that is the heritage of Anglo-Saxon Puritanism, and Buñuel, the Jesuit schoolboy turned high priest of heresy, may on the surface seem a dubious decision, but they sing in a weird harmony. (The prospect of a Moll Flanders by Buñuel is not unintriguing.) The resulting film is distinctly Buñuelian, but not because the Aragonese anarchist sets out to tear up the source text; he’s content instead to scribble and doodle jokes in its margins. What major alterations there are to Defoe’s narrative are mostly commonsensical bits of streamlining—Buñuel dispenses with material detailing Crusoe’s life before and after the island, for example. Something of the first-person, subjective perspective of Defoe’s novel is retained in the form of voice-over in the style of his narration, but Buñuel’s images tell a story that Defoe’s diaristic accounting does not, overlaying a second, ironic perspective. While both Defoe and Buñuel, as true artists, allow space in their works for ambiguities to flourish, it may be said that for Defoe, hacking a Christian civilization in miniature out of the wilderness is an act as essentially noble as Christian civilization itself. For Buñuel, the imitation only serves to highlight the absurdities inherent in the original.

Buñuel’s film is given its texture through a series of curious incidents, the sort of elisions one might read between the lines of the journal kept by Defoe’s Crusoe, some compromising—as when Crusoe treats himself to a drunken spree—others overlooked incidents of the everyday uncanny. In dire hunger on first landing, Crusoe cracks open an egg filched from a nest, and inside finds a live, downy baby bird. Shortly after recovering a pet cat and dog from his foundered ship, Crusoe, a social-planning Noah, pauses to stamp to death some stowaway rats that have made their way to the island. These scenes occur nowhere in Defoe’s novel, nor does that of Crusoe, desperate to hear another voice, reciting Psalm 23 aloud in a part of the island designated the “Valley of Echoes,” his words returning to him as the eerily familiar voice of God. The nagging absence of sex, unmentioned by Defoe, Buñuel teasingly refers to in two scenes: in one, a makeshift scarecrow rigged by hanging up a woman’s cornflower-blue dress draws Crusoe near to it as the fabric wavers alluringly in the breeze; in the other, Friday (Jaime Fernández, brother of director Emilio), the aboriginal South American who becomes Crusoe’s companion in his last years on the island, goes on a cross-dressing jape and earns a stern reprimand from Crusoe, seemingly troubled by the possibilities this suggests.

Dan O’Herlihy as Robinson Crusoe in Robinson Crusoe (production photo). Image courtesy Leopardo Filmes.

Observing the figure of Crusoe in the round, Buñuel finds the prismatic reflections of all manner of hermits, cranks, and holy fools. In his parti-colored outfit of patchwork pelts, O’Herlihy looks at times the role of the frontiersman, a daffy Davy Crockett. At another moment, stooping to converse with insects, he appears with his squared-off John Brown beard like some Old Testament patriarch, or even the Almighty himself. Buñuel’s beasts of the field are not mere chattel, but vivid individual personalities, and scenes detailing the death of Crusoe’s dog, Rex, exhibit a pathos that Buñuel rarely allowed himself. About humans, the film is less sentimental. As Crusoe broods over a newly built homemade bomb—his plan to blow the occasional cannibal visitors to his island sky-high visualized as a Wile E. Coyote fantasy of smiting wrath—he recalls other bearded malcontents plotting to upend the world from an obscure redoubt, a Kaczynski or a Bin Laden.

The screenplay—credited to Buñuel and “Philip Ansel Roll,” a pseudonym for Butler, who, per O’Herlihy, was increasingly distressed by the director’s disregard for the script’s realism during the shoot on the Pacific coast near Manzanillo—takes its greatest liberties after Crusoe is joined by Friday. Lost at sea while on a voyage to export slaves from Africa, the pampered gentleman Crusoe is forced in his new domain to fall back on his own resources. But man is defined by company, and the presence of Friday permits Crusoe to cast himself as white again, with all the implicit airs and privileges. Here Buñuel’s Crusoe assumes the form of still another archetype of gloomy isolation: he is Robinson Crusoe el jefe, Robinson Crusoe the tinhorn dictator of a tiny banana republic.

This role, too, Crusoe leaves behind, long enough at least to work together with Friday to secure, through comradeship in arms, their safe passage off the island. His final form, in gentleman’s sherbet-colored silken raiment, is that of a middle-aged fop, and Buñuel is as ambivalent about the gift of the protagonist’s deliverance as he is of society itself. As Crusoe sets sail, a final flourish is heard, the distant, plaintive sound of a dog’s barking—the call of the wild, beckoning him back from the return to normality.

Nick Pinkerton is a Cincinnati-born, Brooklyn-based writer. His writing appears regularly in Artforum, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, frieze, Reverse Shot, and sundry other publications, and in areas of interest, he covers the waterfront.