Ben Ratliff

Ben Ratliff

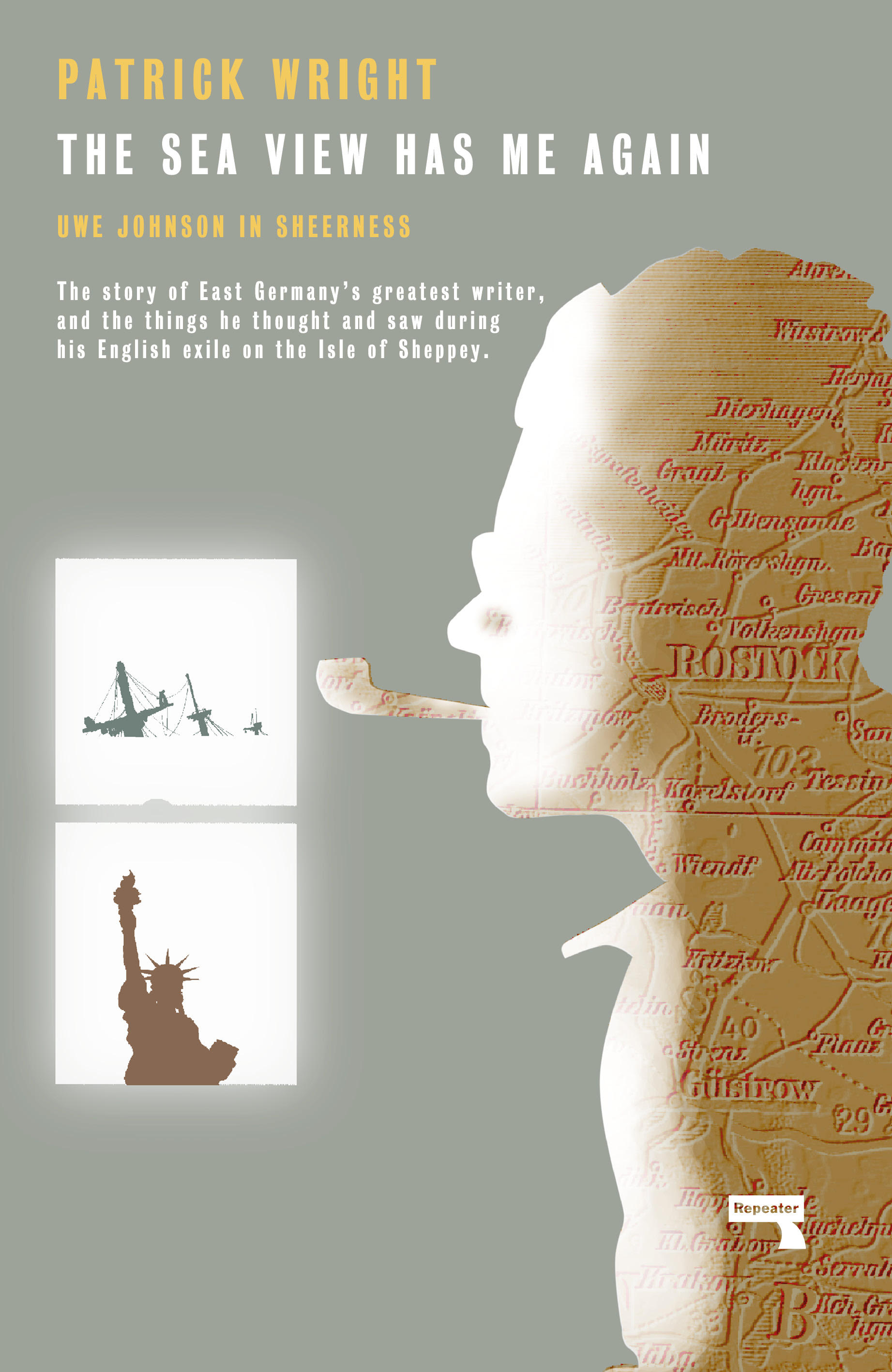

Patrick Wright offers a sideways biography of the writer Uwe Johnson.

The Sea View Has Me Again: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness,

by Patrick Wright, Repeater, 733 pages, $29.95

• • •

The first telling of a life tends to be heroic, dramatic, and efficient. But a second telling can always be imagined, built of stories left out of the first for any number of reasons. This second, inverse telling might be arduous, indirect, speculative, and sad. It might provoke a reaction of what-exactly-is-this?, like Rachel Whiteread’s negative-space sculptures of building interiors. It might also be as valuable as the first.

I am describing something like the experience of reading Patrick Wright’s tangent-besotted, sort-of biography, The Sea View Has Me Again, about the final phase of the East German writer Uwe Johnson. But it is mostly about Sheerness, on the Isle of Sheppey, an estuarial marshland forty miles east of London with a history of libertarians hardened by government neglect and mosquito-borne disease. This was where for ten years the bald, columnar man-from-elsewhere who introduced himself at the pub as “Charles” worked fitfully, devoured the Sheerness Times Guardian, alienated his wife and child, drank, and endeared himself to almost nobody. In February or March 1984—his body was not found for weeks—he died alone at home while opening that night’s third bottle of wine.

A more standard book on Johnson might emphasize, say, that he had a terrible childhood and early success. Wright offers only the basic verifiable events. Johnson grew up in a small Baltic-coast town; the advance of the Red Army forced his family to flee to Mecklenburg—then briefly occupied by the British until it was ceded to the Soviets—described by Wright as “a famously backward and peripheral province ever since the decline of the Hanseatic League in the fifteenth century.” His father disappeared, perhaps jailed for obscure reasons, but who knows. He attended the local school as a refugee child; later, after Johnson moved to West Germany in 1959, he resisted this designation, not wanting to feel beholden to either side. He sought a kind of objectivity free from government regulation; he needed to live above the wall.

That same year he published his first novel, Speculations About Jakob, which won major prizes and was considered not just literature but long-awaited news from the psyche of the GDR. He joined Gruppe 47, the loose affiliation of writers that included Ingeborg Bachmann, Günter Grass, and Heinrich Böll, who collectively assumed the task of rethinking German-language literature, and the language itself, after Nazism. Much was expected of this man. The opportunity was his to seize, subvert, or waste. He may have done all three.

Johnson’s great achievement was Jahrestage—in English, Anniversaries—a novel started during the two years he lived in New York City, and published in four volumes over thirteen years, from 1970 to 1983. The full English translation by Damion Searls, published in 2018 by New York Review Books, runs to 1,668 pages. It is built of 367 day-by-day chapters, describing in tweezer specificity the life of Gesine Cresspahl, an East German emigrant living with her young daughter on Manhattan’s Upper West Side as 1967 turns to 1968. Spliced into neighborhood scenes and daily readings of the New York Times is a parallel story with a different tempo: forty years of her family’s background in Mecklenburg, through Nazism, the Soviet occupation, the Cold War, and Gesine’s departure for America: the long horizon of European political hysteria.

Wright shows us how Johnson’s colleagues would later describe him: as something like an alien, a stone mass. Grass said that “being a stranger was of great importance to him.” Gerhard Zwerenz called him “a statue of lost cultures.” Max Frisch noticed in him a “logician” who could also be “completely irrational.” Gunter Künert, in a line carried through the book, perceived a man under a “bell jar of strangeness.”

Why Uwe Johnson would move to Sheerness to continue his great project may be less mysterious than it might appear. In 1974, England was neither communist nor hard-capitalist, and above all Sheppey reminded him of home. “I have yet to find anyone,” Wright notes, “who can immediately distinguish photographs of the Swaleside marshes of Sheppey, from those on the flat and watery terrain between the Baltic and the shallow inland lagoon known as Saaler Bodden near Ahrenshoop on Fischland.”

What’s really interesting here is what Wright is doing. You are given just enough of the primary telling, Johnson’s upbringing and claims to fame. You are also given much from Johnson’s letters to friends, including Frisch and Hannah Arendt, and bits of translations from Johnson’s writing about Sheppey, newly translated by Searls. But this is a study of the spaces around the statue much more than the statue itself. It encompasses what is essentially a short critical biography of Ray Pahl, an English sociologist who conducted deep, patient research on the island in the ’70s and ’80s. A history of the Sheerness sea wall, with citations from hydraulics scholarship and Concrete Quarterly, takes up twenty pages. A prolonged legal squabble over a drainage ditch fills nearly another twenty. It may not immediately be clear why or how this task can be sustained. I loved Anniversaries, yet several hundred pages into Wright’s book I wondered whether I could stand to read so much about a suburb where dreams have gone to die since the 1660s.

I warmed to it seriously. Sheppey is Xanadu for Wright, who is not a biographer or a journalist but a sort of spirit-ethnographer, patient and attentive to change and complexity. (Among Wright’s other books is A Journey Through Ruins, a vibe-reading of late ’80s England via East London under Thatcher.) And so Sheppey becomes a cluster of metaphors for Johnson and his struggles, which Wright does not particularly force into relevance; he lets them appear and expand. Just as the island’s shipyard economy had declined through the twentieth century, the East German writer himself became deindustrialized as well. Sheppey is unhealthy, unfashionable, vibrating with concealed paranoia. So was Johnson.

Then there is the SS Richard Montgomery, sunk off the Sheerness coast in 1944 and visible to Johnson from his upstairs window, its masts still today poking above the water level. It was one of many American “liberty ships” used to carry munitions for Allied powers in Europe. Though many of its bombs were rescued from the wreck, an estimated 1,400 tons still threaten to crater out the sea floor and shatter windows for miles around. A hulk cracked in half during the war, full of undetonated ordnance, out of sight but very much there: Wright lavishes eighty pages on the super-metaphor.

One of the most striking primary-tale details is told only in passing. Johnson lived on unrecouped advances from his German publisher, Suhrkamp, and before his death made preparations to start paying them back. When he finally died, he left Suhrkamp almost all his physical possessions. I am amazed by this. I have never heard of a writer doing such a thing. Johnson’s bequest is absurdly ethical, maybe even heroic. I admire Wright’s implication that it is no more a key to his subject than a quotation from Concrete Quarterly.

Ben Ratliff is the author of four books, including Every Song Ever.