Sarah Resnick

Sarah Resnick

Set in Las Vegas, Nina Menkes’s 1991 film tracks a castoff of

conspicuous consumption.

Tinka Menkes as Firdaus in Queen of Diamonds. Photo: Arbelos Films.

Queen of Diamonds, written and directed by Nina Menkes, Brooklyn Academy of Music, 30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, April 26–May 2, 2019

• • •

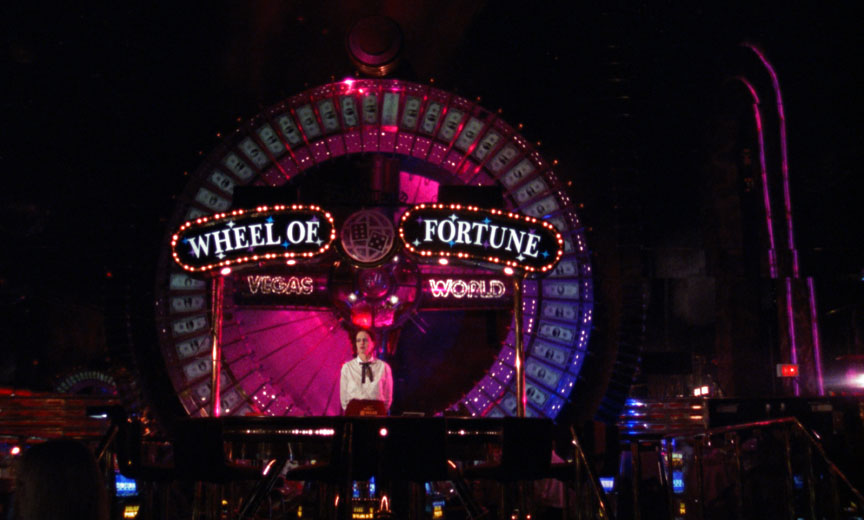

Parched, tawny wastes; shriveled blades of aloe: Queen of Diamonds (1991), the second of five fiction feature films made to date by American director Nina Menkes, trades the Las Vegas of glut—of excessive barbarity and intoxication, greed and tempestuousness, lust and loss, expectation and disappointment—for the Las Vegas of lack. A single fan palm stands crowned by a garland of flames. Spindle-shanked masts ornamenting a trailer-park shantytown strain upward for high-frequency radio waves. A freight train edged by vacant billboards and crossbar power lines trundles toward a hazy mountain vista.

Queen of Diamonds. Photo: Arbelos Films.

In Queen of Diamonds, Menkes offers a trance-inducing tour of an overdeveloped city—a stand-in for our overdeveloped country—by fixing her camera precisely on the castoffs of conspicuous consumption. Las Vegas’s totemic opulence flickers mirage-like only in the imagination. The hero of the film is named Firdaus. Played with taut disaffection by Menkes’s younger sister, Tinka, Firdaus is a croupier at the Par-a-Dice casino; between shifts, she drifts alone through the city’s outskirts. Her circumstances are otherwise vague. She lives in a one-room motel apartment. Her next-door neighbor routinely batters his soon-to-be wife, which she hears and sometimes sees. She is married, although her husband’s whereabouts are unknown, as eventually we learn, even to her. Firdaus doesn’t seem to care. As she moves about town (always on foot), strange men seize on her solitude as an invitation to trespass. Firdaus retreats into indifference. Her days wilt with apathy.

Tinka Menkes as Firdaus (left) in Queen of Diamonds. Photo: Arbelos Films.

Menkes’s movie, recently restored in 4K resolution by the Academy Film Archive and the Film Foundation, borrows the name of its protagonist from Woman at Point Zero (1975), the renowned novel by the Egyptian physician, psychiatrist, and writer Nawal El Saadawi. In the book, we meet Saadawi’s Firdaus in a Cairo prison on the eve of her execution; following a life sodden with subjugation and betrayal, she has been sentenced to death for killing a man. This man had recently forced her to accept him as her pander, thereby stealing from her the sovereignty that after decades of striving she found she could approximate only by forgoing both marriage—“the system built on the most cruel suffering for women”—and socially accepted employment for sex work. Even in the face of death, Firdaus refuses to search out a pardon. For that she would have to apologize. She does not want to apologize. “I am a killer,” she says, “but I’ve committed no crime.”

Tinka Menkes as Firdaus in Queen of Diamonds. Photo: Arbelos Films.

The film shares little with the novel by way of setting or plot, but what links Menkes’s Firdaus to her namesake is her isolation, her invisibility. Both are diamonds, so to speak: forged by pressure, their glittering core has long been inhumed within a colorless, compacted, unyielding facade. The writer, in some ways, has the easier task; her medium is words, and Firdaus on the page relays her invisibility by describing it. The director, meanwhile, must contend with the pith of her own image-based medium: the protagonist must (literally) be visible if she is to be the protagonist at all. Menkes embraces the challenge: the screen-based Firdaus, who rarely speaks—the film contains little dialogue—appears in nearly every shot. Menkes triumphs by always framing Firdaus and her ashen complexion in medium and long shots; never do we see her face in close-up, that “transparent window to the soul,” to borrow from film scholar Richard Dyer. Our Queen is protagonist and at the same time background character.

When Queen of Diamonds debuted at the 1991 Sundance Film Festival, it was among the first features directed by a woman to be shown at the Utah resort-town fête. The movie was well-received by critics, although it eventually retreated, along with Menkes’s other films—all but one of which ply dream logic to woman-centered narratives of estrangement—into something approaching obscurity. Since then Queen of Diamonds has been hard to see, unless you were lucky enough, as I was in 2012, to catch it in a rare theatrical screening on the occasion of a Menkes retrospective at New York’s Anthology Film Archives. Queen of Diamonds shares not only the formal sophistication and structural rigor of Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970) and Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975) but also their themes: female alienation and the ways that passivity, muteness, and a refusal to engage can serve as forms of resistance to patriarchal oppression. Ironically, these same themes helped to eclipse the three works—and many others like them—for too long. In an interview in 1991, Menkes recounted how, at the conclusion of a showing of Queen of Diamonds in the AFI’s Women Make Movies festival in Washington, DC, three men in the audience booed: an auguring, perhaps, of its fate to land in the cellar of difficult films made by women.

Tinka Menkes as Firdaus in Queen of Diamonds. Photo: Arbelos Films.

Menkes, who grew up in California, studied dance and choreography before pursuing filmmaking, which may explain the ease with which she relinquishes certain customs of American cinematic storytelling while remaining in a narrative mode. Queen of Diamonds’ steady assemblage of wide shots and long, static takes, in which Firdaus is often stationary or inanimate, conjures a claustrophobic restlessness. Will she ever move? As if she may settle in place, the ground giving way as she sinks gradually downward. Only once does the film’s torpor cede to freneticism: cards (an eight of clubs, a four of hearts) piled faceup on green baize, gamblers set in concentration, the glint of crimson-lacquered nails, Firdaus beset by shimmering catenary arches and mirrored tile, stacked chips, nervous tics. For seventeen minutes the anticipation accumulates. The discordant din of electronic slot machines abrades by the time the casino gives way to morning twilight, but no climax emerges to usher in a resolution. Nothing happens. There is no fulfillment, no virtue, no moral benefit that redeems the drudgery of a blackjack dealer’s long night. There is only futility.

Sarah Resnick was born in Canada and lives in New York. Her short stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in n+1, Bookforum, BOMB, and frieze, as well as in the Pushcart Prize and Best American Essay anthologies. A former editor of Triple Canopy, she is a 2019 Canada Council for the Arts grantee.