Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

What ever happened to the glue-stick?: a new show chronicles

the past fifty years of zine history.

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, installation view. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Paula Abreu Pita.

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, organized by Branden W. Joseph and Drew Sawyer, Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, through March 31, 2024

• • •

For me, as for many adolescent fanzine editors, the first cut was the deepest. My zine was called Eheu! Caudex! (Latin for Alas! Blockhead!) Of words it had plenty—yacking screeds about racism, Sartre, Shelleyan Orphan. But images? The only way to get those was to steal magazines—from a local corner store, a doctor’s waiting room—and then, alone in my bedroom with trembling fingers, to let snip. Decades later, I still recall the sound of paper being cut, my heart beating, the question in my head—am I a delinquent? I recall my answer too: I feel free!

To think of fanzines is to think of our younger, stumblebum selves. Warmly, bemusedly. Was that who I was? Oh God—I’m still that person now! At their best, they’re unfiltered, expressways to our hearts, half-cooked documentation of us tottering out of teen-dom. Private lives going public. Not all fanzines are the same—far from it—but they tend to thrive on ferocity, something that feels (if only to their makers) like authenticity, a comically blunt belief in “us” versus “the man.” The key is in the prefix “fan”—with all that word’s need and hunger, unreason of passion, crotch-clammy intensity.

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, installation view. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Paula Abreu Pita.

Copy Machine Manifestos, currently showing at Brooklyn Museum, favors the term “zines” over “fanzines.” A thousand of them (including videos and sculptures), mostly North American. It’s also about the “artists” who make them—not chippy upstarts, tortured hobbledehoys, blaggers hoping to get free swag from record companies (“It’s for a review!”). Did the writers and editors think of themselves as artists when they were assembling their publications? Do artists think about and produce fanzines—sorry, zines—differently from your average glue-stick wielder? Do zines, in times past bartered, sold via mail order, or racked up tight in indie stores, contaminate art galleries? (Or vice versa?)

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, installation view. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Paula Abreu Pita.

It’s easy, at first, to set aside reservations. How thrilling to have the opportunity to see so many obscure, near-mythical examples of splenetic, outsider, weirdo printed matter. Some will feel there aren’t enough examples of science-fiction or folk fanzines from the 1930s through the 1960s. But the overlaps with mail art, comics, and queer pamphlets are very much on display. The names alone are gigglesome. The group-compiled New York Correspondence School Weekly Breeder, Raymond Pettibon’s New Wavy Gravy, Vaginal Davis’s Rich Jewish Husband, Gene Barnes’s, aka Portia Manson’s, Hippie Dick! (Issues of the latter did indeed sport covers of hippie dicks.)

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, installation view. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Paula Abreu Pita.

Seeing is almost all you can do in this show. But few zines, at least until recent times, were wholly without text. The writing could be informative, autobiographical, pustular with social critiques; it wanted, and sometimes deserved, to be read. Reread, even. Maybe passed on to pals. How that writing was presented—in block lettering, ransom-note cut-ups, pastiche of mimeograph-machine poetry—was inseparable from its meaning.

Copy Machine Manifestos does feature a room with a small, seemingly random selection of zines that can be handled. That—apart from a few spreads and paste-ups—is all. This is a show about fanzine covers more than it is about fanzines. Contemporary print curators grapple with issues of tactility and totality—some more ambitiously than others: Steffani Jemison and Jamal Cyrus, in Museum as Hub: Alpha’s Bet Is Not Over Yet! (New Museum, 2011), included complete reproductions of more than five hundred Black American publications from 1902 to 1940—facsimiles of all of them available to read and pore over.

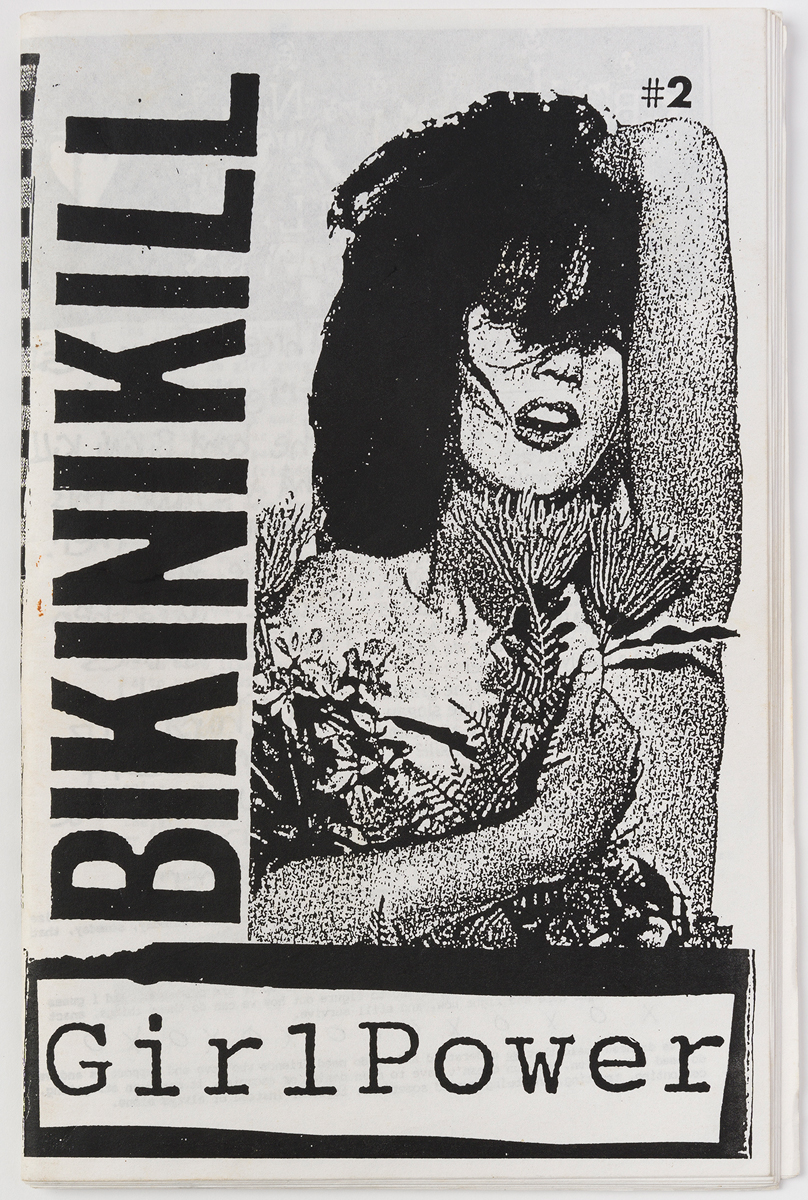

Kathleen Hanna with Billy Karren, Tobi Vail, and Kathi Wilcox, Bikini Kill, no. 2, 1991. Photocopy, saddle-stitched, 8 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches. Photo: David Vu.

Noise bleeds out of this show’s zines. Many editors were also musicians —Cary Loren (Destroy All Monsters), Barbara Ess (The Static, Y Pants), Kathleen Hanna (Bikini Kill)—and their publications were miniature sonic weapons, interference devices, deviance broadcasts. For them, as for queer activists in the 1980s, Silence = Death.

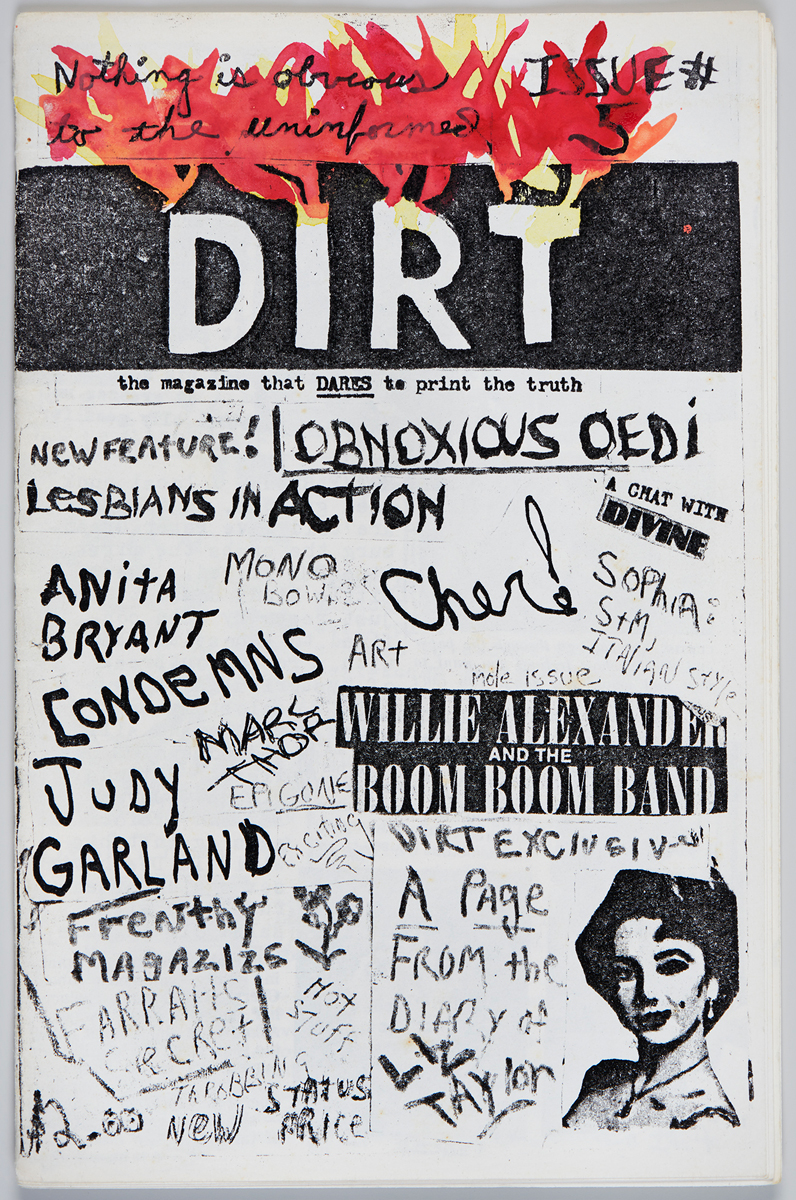

Mark Morrisroe and Lynelle White, Dirt, fifth issue, 1975/1976. Xerox, 8 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches. © Estate of Mark Morrisroe.

The pistols and syringes in Redrum by Tommy Turner (with David Wojnarowicz), the hip-hop stylistics of David Schmidlapp and Phase2’s International Graffiti Times, the downtown entropy in Mark Morrisroe and Lynelle White’s Dirt: such zines channel the din of screeching subways, post-punk collage, the white noise of corporate media consolidation, Network’s Howard Beale yelling “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore.” The loudest zine in the show? W. Wayne Karr and Cory Roberts-Auli’s early 1990s Infected Faggot Perspectives—“Dedicated to keeping the realities of Faggots living with AIDS and HIV Disease IN YOUR FACE until the Plague Is Over!!!”

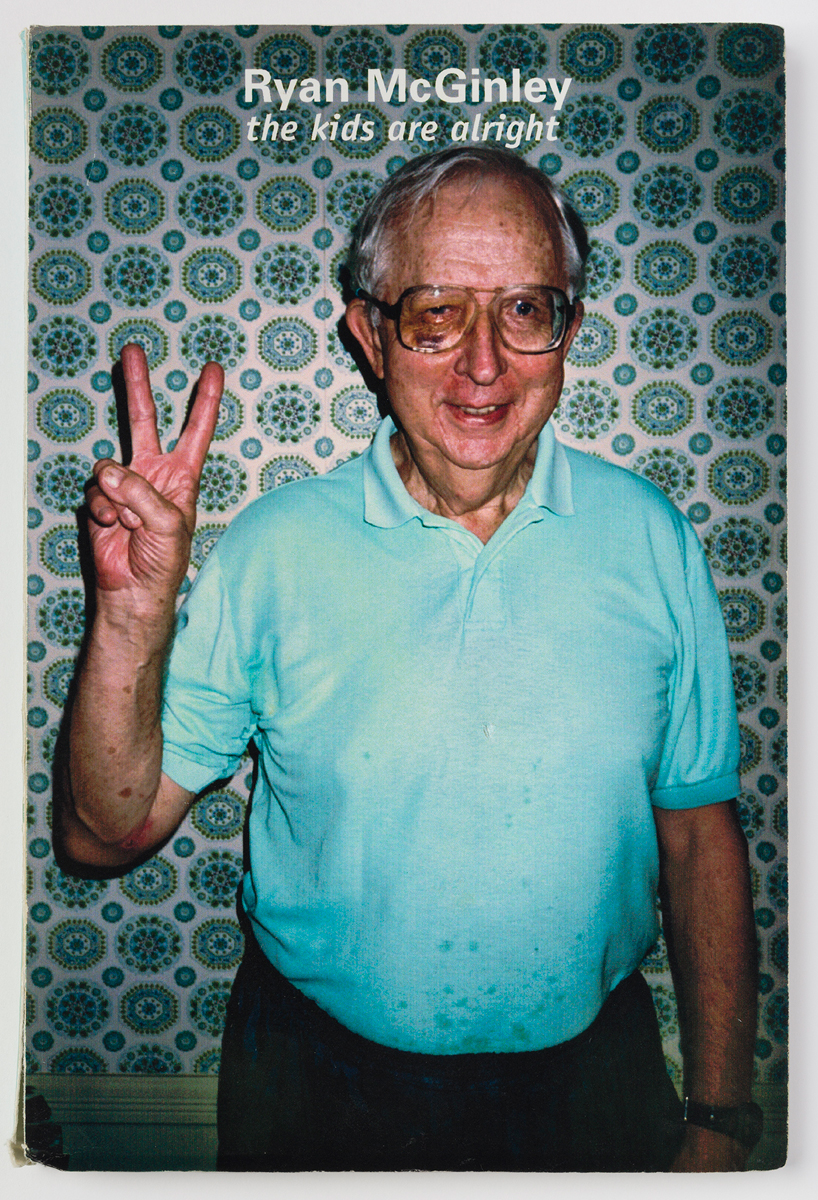

Ryan McGinley, the kids are alright, 1999. Photocopy, saddle-stitched, 8 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches. Photo: David Vu.

Running chronologically, Copy Machine Manifestos loses steam by the mid-1990s. The internet may not have made zines redundant, but it forced them to develop new rationales. Historically, zines had been an attempt to bypass publishing gatekeepers, the print equivalent of pirate radio stations; then, with the early internet offering at least the illusion of global accessibility, they represented strategic ring-fencing, the aura of scarcity, the ethos of scaling down. Zines had always been as much about process as product; now, with desktop publishing, click-and-drag replaced ripped-and-torn as a mode of designing—and as a labor process. Erratic stapling and toner levels became uncommon; the paper got nicer, scanning replaced xerography, and there was far more photography—often color. So many of the zines from the first decade of the 2000s displayed in the show are full of dudes goofing off, trust-fund jackassery. They resemble—ye gods—little more than American Apparel ads.

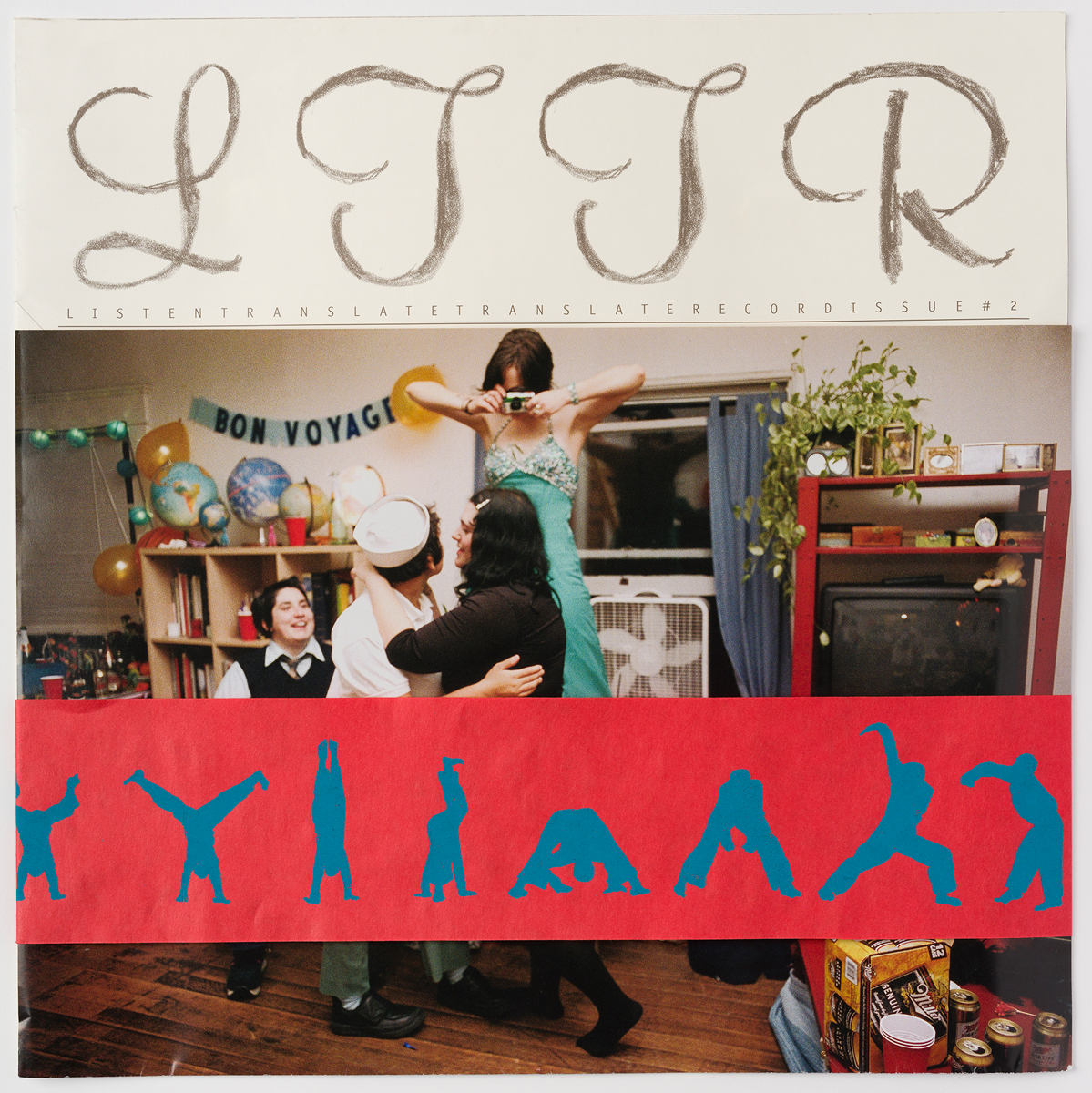

LTTR (Ginger Brooks Takahashi, K8 Hardy, Every Ocean Hughes, Ulrike Müller), LTTR, no. 2, Listen Translate Translate Record, August 2003. Offset, folded, with one booklet, one screen-printed band, one altered tampon, compact disc, 12 1/2 × 12 1/2 inches overall. Photo: David Vu.

Worse was to follow: respectability. Since the 2010s, zines have been more and more used as marketing devices, slipped into pricey reissue LPs, hailed as formats of edgy “inclusivity” and “social impact.” They are collected, reprinted in hardback editions, taught in colleges (sometimes by the Reagan youths and riot grrrls who originally made them). They are theorized, historicized, elevated (going by some of the claims in the show’s accompanying publication) to none-more-subaltern, revolutionary status.

Pat McCarthy, still from Babylon Pigeons, no. 13, Photocopying Pigeons, April 2019. Color video, sound, 9 minutes 43 seconds.

The final room in Copy Machine Manifestos is exemplary: installations, videos, and zines by pre-professionalized artists whose art is as eloquent as it is enervating, their publications claggy with the language of community, pedagogic activism, world-making. Extractive Industries, the name of an art piece by Demian DinéYazhi’, even reads, “We deserve dignity over solidarity / we desire survival over statements / we demand resources / over acknowledgements.” In neon!

Zines, at their most glorious, are indifferent to dignity, reckless in the statements they reel off, determined to make a virtue of their limited resources. Back in 1978, the editors of a book called Copyart likened the photocopier to a “magical machine,” something that produced the “unplanned” and “unexpected.” All the magic in Copy Machine Manifestos is from another time, another country.

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for the Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.