Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

A stalwart of the UK’s Black Audio Film Collective gets his first US survey.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 (installation view). Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

John Akomfrah: Signs of Empire, New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through September 2, 2018

• • •

It’s hard to evoke the thrill and bewilderment of seeing John Akomfrah’s films back in the 1980s. Born to Ghanaian parents in 1957 and brought up in London, he was one of seven members of the Black Audio Film Collective, a gang of young British para-academics, theory heads, and image scientists who developed a body of work—shown in galleries, picture theaters, and on television—that flouted all the rules about how black and immigrant stories could be told. Instead of those approaches associated with current-affairs news programs—social realism, “frontline” dispatches, the rhetoric of crisis—Akomfrah, who directed most of the BAFC features, was developing a proto-essayistic style that was allusive and elliptical, sonically dense, compelled by the mysteries of the archive. In television interviews, he was—and remains—both plummy and incisive, adept at discussing Althusser and Antonioni in the same sentence, brilliant at joining the dots between structuralist cinema and revolutionary politics.

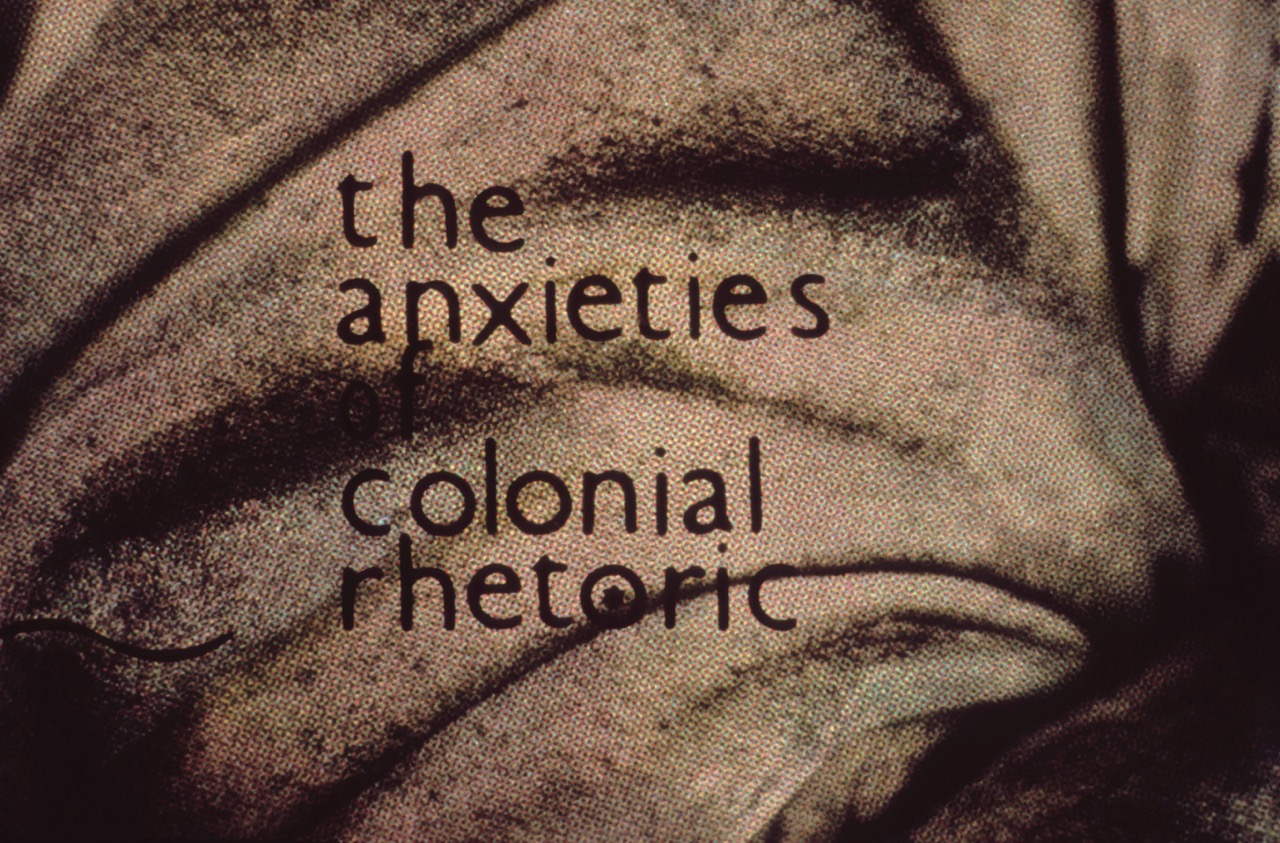

The Black Audio Film Collective wound down in 1998. In recent years, especially after a retrospective of his work appeared in 2002 at Documenta 11, Akomfrah’s art has migrated to the gallery world. While individual pieces have been screened across the US, John Akomfrah: Signs of Empire at the New Museum is his first survey in this country. It takes its name from the earliest Black Audio work, Expeditions One: Signs of Empire—a twenty-six-minute slide-tape piece from 1983 for which the underfunded collective culled copies of National Geographic and second-hand books for images of colonial statuary, sepia photographs of mutilated Africans, and verse from Victorian-era children’s poetry. They deployed Letraset to overlay these with phrases—“the hinterlands of narrative,” “the impossible fiction of tradition,” “binaries of abjection”—that sound like notes taken from a poststructuralism lecture, and framed them so that they echoed the text-image art of Victor Burgin, the typographical experiments in Derrida’s Glas, and the record sleeves of postpunk designers such as Vaughan Oliver.

John Akomfrah, Expeditions One: Signs of Empire, 1983 (still). Single-channel 35mm color Ektachrome slides transferred to video, sound, 26 minutes. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Expeditions One is also built around a complex sound design by Akomfrah’s long-term collaborator, Trevor Mathison, that is full of tape delays and muted loops, an acoustic ghostscape that includes the posh cadences of Queen’s Counsel Sir Ronald Bell talking about second-generation West Indians in Britain (“I think they don’t know who they are or what they are”). Akomfrah’s best-known film as part of Black Audio, Handsworth Songs (1986)—on view as part of a screening series of single-channel works—heightens the hauntology by having a woman on the voicetrack announce, “There are no stories in the riots; only the ghosts of stories.” The riots she’s talking about took place in multiracial Handsworth, West Midlands, during September 1985 and led to a wave of disturbances across the country. Conservative commentators claimed they proved that Britain’s inner cities were under siege by feral foreigners; many of the left, in their clamor about the “present crisis” and in their demands for Something To Be Done, seemed equally unable to discuss immigration in a historically inflected fashion.

What made Handsworth Songs so exhilarating is that it rejected the amnesiacal “state of emergency” rhetorics of both the right and would-be radicals. It circled around, drifted across, and reverse-geared from “the riots,” refusing their centrality to questions of race and migration in Britain, and instead opening new spaces for reflection and speculation. The polyphonic voiceover incorporated elements of epistolary fiction as well as political analysis; Mathison’s sound design, bleak with clangs and thumps partially influenced by industrial bands such as Test Department and Cabaret Voltaire, fashioned a post-imperial musique concrète; slowed-down footage showed a revolving clown mask and a young man trying to evade baton-wielding policemen. They all made Handsworth Songs both militant and ambiguous. Militantly ambiguous.

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation, 2012 (installation view). Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

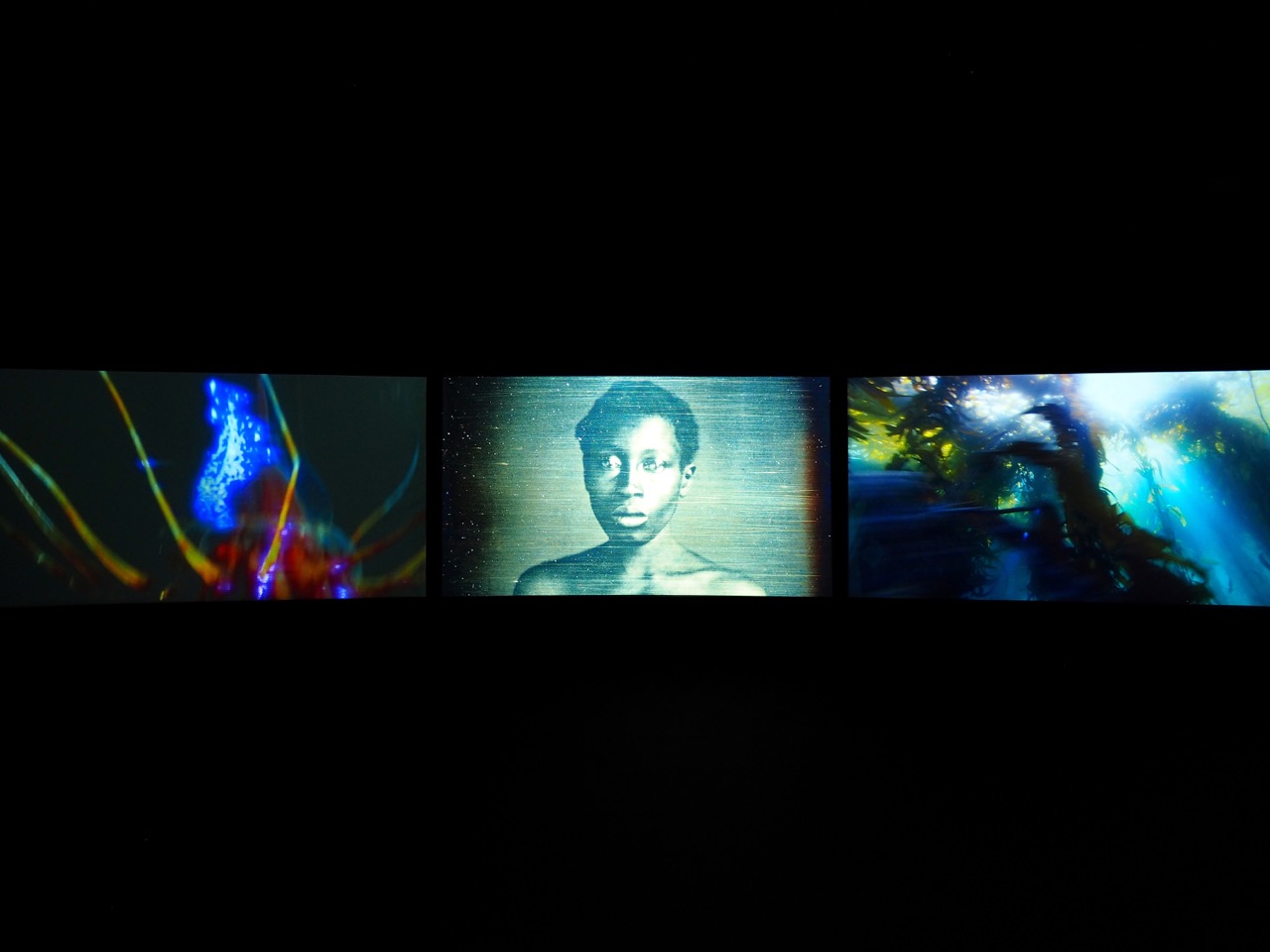

The Unfinished Conversation (2012), a three-screen installation, serves as a companion piece to Akomfrah’s more conventional biographical portrait The Stuart Hall Project (2013). The multiple channels—often offering triptychs of landscape shots, black-and-white footage of uprisings in Hungary and Vietnam, and family photographs of the pioneering, Jamaica-born cultural theorist—convey the jostle and juxtaposition that also characterized Hall’s activities, whether in the mimeographed publications he edited and wrote for, or in the heated public debates to which he often made key contributions. Akomfrah challenges us to interpret and make connections between, say, Hall talking about his love of William Blake’s poem “The Tyger,” footage of a woman giving birth, and gospel singer Mahalia Jackson in full devotional effect. This leads to conjecture and instability; appropriately so, for, as Hall is heard to argue, “Identities are formed at the unstable point where personal lives meet the narrative of history.”

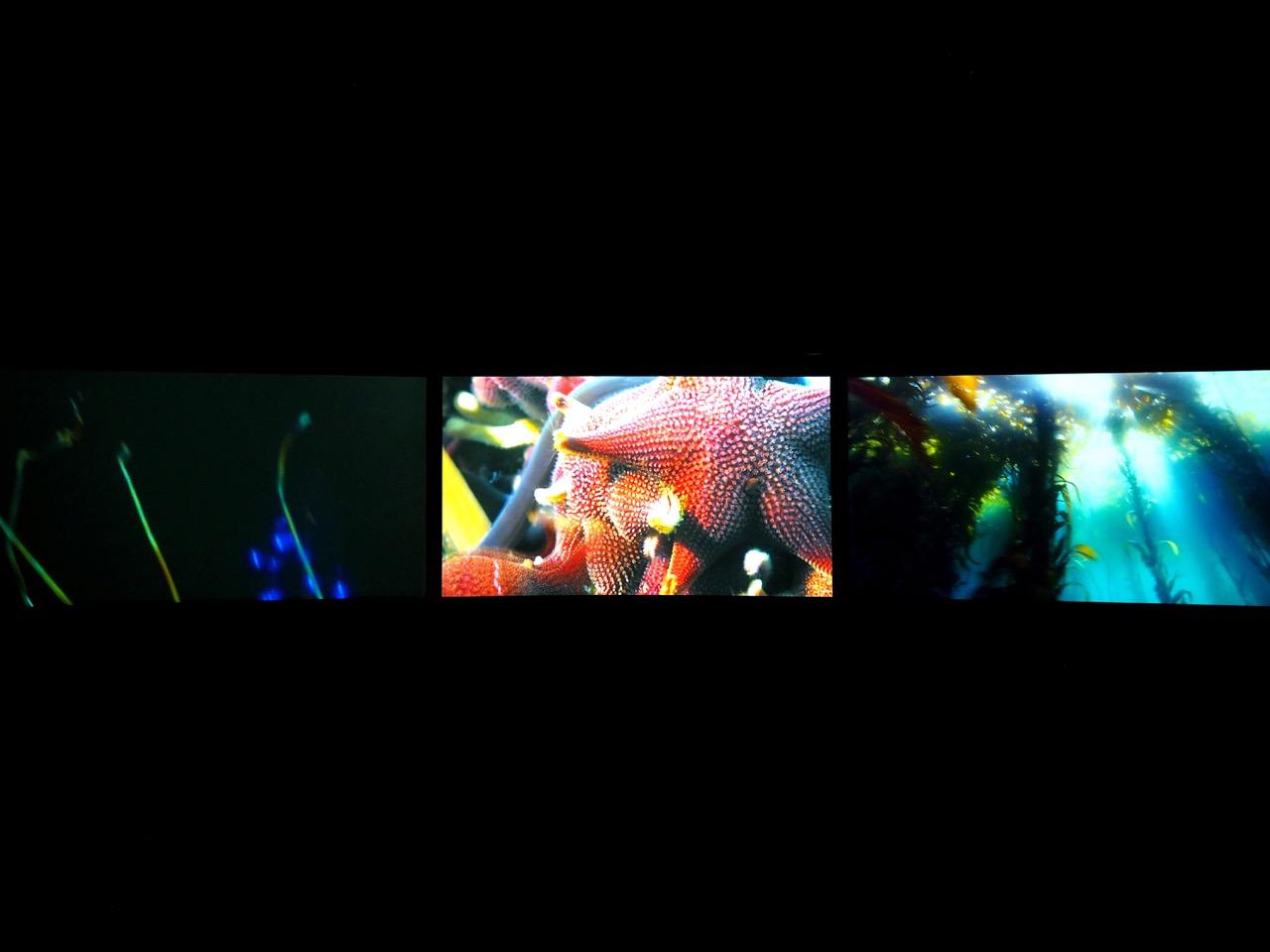

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 (installation view). Three-channel HD video installation, 7.1 sound, color, 48:30 minutes. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

At the heart of the New Museum show is Vertigo Sea (2015), a three-channel work that, like Patricio Guzmán’s The Pearl Button (2015) and Philip Scheffner’s Havarie (2016), is an exercise in hydropoetics. It shows water and seas, fish and whales, rafts and trawlers. It invokes the slave trade, Vietnamese boat people struggling—often in vain—to get to Hong Kong, the Argentine military junta’s policy of dumping the bodies of dissenters in the ocean, and contemporary migrant flows from the Global South. It features a wide range of voices—African chants, the testimony of a Nigerian fisherman, radio-news reports of deaths in the Mediterranean, quotes from Melville’s Moby-Dick, Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and Woolf’s To the Lighthouse—that create a kind of hydrophonic motley. Archival footage spanning the twentieth century is supplemented by staged scenes involving white and black figures in period dress (one of them the eighteenth-century abolitionist writer Olaudah Equiano), modern bicycles and strollers placed in low-level water, and a beach full of clocks.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 (installation view). Three-channel HD video installation, 7.1 sound, color, 48:30 minutes. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Water is intersectional. Water connects everything. “Watching the water,” artist Roni Horn once wrote, “I am stricken with vertigo of meaning. Water is the final conjugation: an infinity of form, relation, and content.” In Akomfrah’s piece, the sea is a mass grave, a liquid plantation, a test site, a mobile factory, a bibliothèque, a barometer of climate change. A fish caught in a net, a trapped polar bear, a whale being gutted: each screen, except when it turns pure blue, keeps disgorging dark, opulent images. It’s hard not to feel engulfed. Like many multichannel works, Vertigo Sea believes that more is more. It also relies a bit too heavily on familiar-seeming footage from the BBC’s Natural History Unit over which you half expect to hear David Attenborough’s voice. I found myself wanting to be estranged from the imagery, to experience the same awe and dread about maritime space inspired by the surrealist films of Jean Painlevé, the techno eschatologies of Drexciya, Stefan Helmreich’s microbial anthologies.

This show is proof of Akomfrah’s ever-increasing embrace by curators, his ever-growing prominence in the realm of white cubes and biennials. It coincides, too, with his work becoming grander both in terms of scale and dimensions, and in terms of transhistorical and geographical reach. It’s also becoming more becalmed, more ruminatively crepuscular, in thrall to the vespertine. I admire his art greatly but wonder if it could risk being less posed and poised, less glazed and more vinegary. A bit of agitation—even a cough or a tremble—would go a long way.

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for The Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.