Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

Orgone gone anodyne: Peggy Ahwesh and Jacqueline Goss’s “theoretical musical” attempts to capture the wild tenets of iconoclastic psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich.

Still from OR119. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

OR119, directed by Peggy Ahwesh and Jacqueline Goss, Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through March 7, 2023

• • •

Wilhelm Reich was a psychoanalyst, but he was also a vegetotherapist, a bioelectrician, an orgonomist. What do these brave new words mean? Perhaps they just make you giggle. As early as 1919, when Reich was an emaciated student in Vienna subsisting on dried fruit and cardboard-tasting oats, he wrote in his journal, “My life is revolution—from within and without—or it’s a comedy! If I could only find someone who has the correct diagnosis!” Freud would call him “the best head” in the International Psychoanalytic Association but later excommunicated him. The FBI offered up its own diagnosis—“dangerous enemy alien”—and had him detained on Ellis Island. His writings on the importance of orgasms, and on the psychosexual maladies that plagued society, won him many admirers. The invention he designed to cure those maladies—an orgone accumulator—irked governmental officials. His books were burned and he was imprisoned. He died, age sixty, behind bars, in 1957.

Reich was . . . a lot. Never one for understatement, he compared his discovery (skeptics might use the word “fantasy”) of “orgastic plasma contraction” to Columbus’s arrival on American shores. At various points in his life, some more lucid than others, he likened himself to Socrates, Savonarola, Giordano Bruno, Galileo, Nietzsche. Christ? Yes, Christ too. He also fancied himself a matinee hero; his son Peter remembered him wearing a cowboy hat styled after Gary Cooper and addressing government officials in the manner of Spencer Tracy. He watched High Noon, Bad Day at Black Rock, A Man for All Seasons. “He thought these movies were about him, and maybe they were . . . He didn’t make a distinction between that and real life,” Peter once said.

Versions of Reich, against which he would have fumed and fulminated, can be found in Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968) and Woody Allen’s Sleeper (1973). Dušan Makavejev was forced into exile after the Yugoslavian authorities banned his carnivalesque biopic W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971). Now, playing at Anthology with an accompanying program, “Wilhelm Reich and the Cinema,” that includes Barbarella, W. R., and other titles, comes OR119. It’s that rarest of birds, a “theoretical musical”—by Peggy Ahwesh and Jacqueline Goss. The directors have set themselves a huge challenge—to make ideas sing, to imbue specialist, quasi-scientific language with soul and élan. How, you may wonder, do they see Reich: Was he a cult leader masquerading as a magus? A renegade intellectual who questioned state doxa? More fundamentally, is it even possible to render such a mutinous, multitudinous life in an hour?

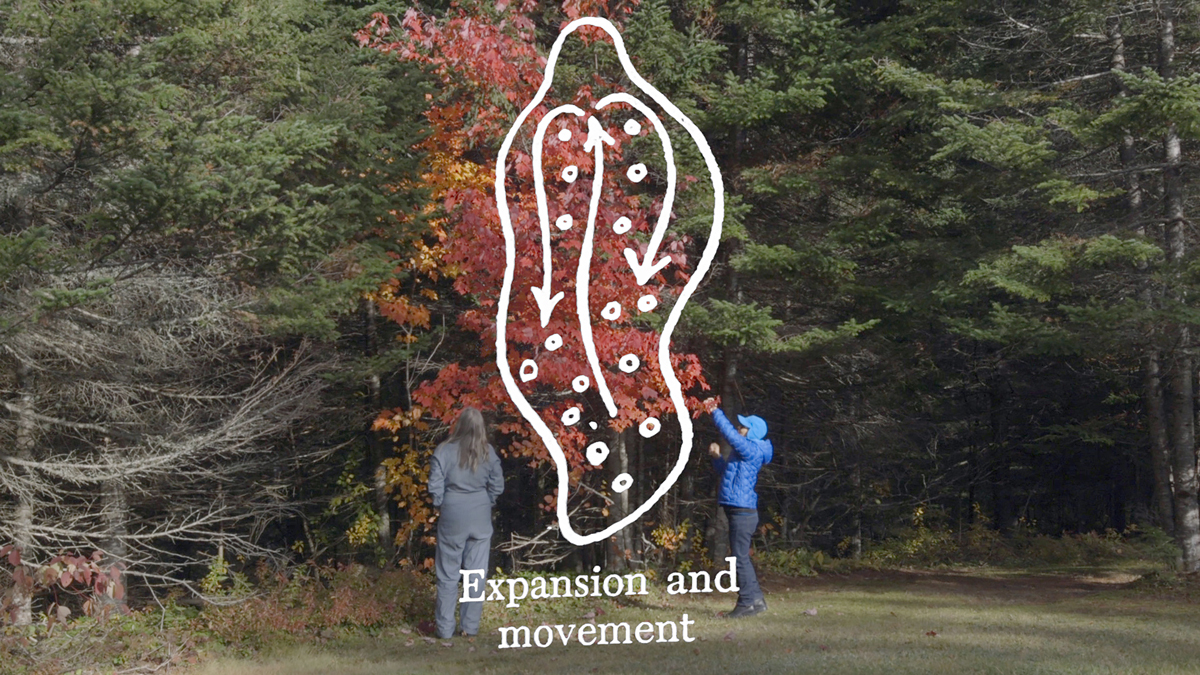

Still from OR119. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

OR119 is set in present-day Orgonon, a 175-acre site in Maine that Reich had bought in 1942 and converted into a home, laboratory, and research center. It was here that he had conducted his experiments in cloudbusting—pointing rows of copper pipes at the sky to alter the atmosphere and produce rain. The film, like many an artist-residency project, gazes at the site lingeringly, straining to hear its frequencies, to channel its atmospherics. Is it more than a sarcophagus? There are gadgets, rusting supplies, a stamper that says “planetary core.” Words on wood that evoke graffiti, prison-cell inscriptions, hermetic ravings. And there: the semi-mythical orgone accumulator. It resembles a ShopRite bomb shelter.

Still from OR119. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Orgonon looks like a perfectly lovely place for a retreat. The performers, among them filmmaker Cecilia Aldarondo and writer Marianne Shaneen, arrange flowers, light fires, carry wood across the grounds. They swim in a lake, scour the sky with telescopes, and appear so commune-cozy that it’s hard to imagine Reich and his colleagues had been the subjects of moral scares, accused by locals of staging sylvan orgies. The Reich associates in OR119 are shown stretching, teasing out patterns in the air like theremin players, deep in their own choreographic reveries. Occasionally, there are chapter headings—“How matter comes to matter,” “learning to live with death”—which seem simultaneously meaningful and meaningless.

Still from OR119. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Reich’s loudest cheerleaders have tended to be men such as William S. Burroughs and Norman Mailer. (The latter compared him favorably with all other psychoanalysts, who he believed were “ball shrinkers.”) Ahwesh and Goss try to rescue him from such dubious boosters by having filmmaker Jennifer Montgomery play Reich and by putting his writings into dialogue with a range of feminist thinkers, including Karen Barad, Anna Tsing, and Betty Dodson (the sex educator who previously appeared in W. R.). These exchanges involve copies of books by Monique Wittig and Hélène Cixous floating underwater, or pairs of performers voicing short extracts from Reich and then, say, Judith Butler. The tone is genteel, gratingly so. What’s missing is friction, dialectical drama.

Some of that does come through in Zach Layton’s protean soundtrack. Reich’s fascination with aliens is suggested by kosmische synths and BBC Radiophonic Workshop–style wibbles. In an unexpectedly Tik-Tokky sequence, three cast members throw shapes in a library while chanting “What do they want for proof? There is no proof” in the fashion of Chicks on Speed or Le Tigre. The worthy didacticism of 1970s Rock in Opposition bands is heard when singers try to scan lines such as “the lack of luster can be understood in terms of some reduction of orgonotic pulsation.”

Still from OR119. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

I left OR119 wanting to object: “There is no argument.” Do Ahwesh and Goss believe, for one, that Reich was a physician-scientist? That’s the claim of the Wilhelm Reich Infant Trust, which controls access to Orgonon and, according to its website, “forever guards against distortion of the work.”

Reich’s ideas are never not timely. He thought about the politics of breathing. About the ways in which capitalism damages mental health (he would surely have applauded Mark Fisher’s attack, in Capitalist Realism, on the “privatization of stress”). He insisted on a woman’s right to abortion and repeatedly decried America’s racism. He was also anti-homosexuality and refused to treat gay clients. He drank, had a volcanic temper, and fell out with countless associates and admirers. It’s impossible to separate his work from his life.

OR119 seems to think it is. And mystifyingly, the film’s goal, according to Ahwesh and Goss, is to “inspire a revitalization of his primary tenet: ‘Love, Work, and Knowledge are the wellsprings of our lives.’ ” That’s pure pablum. The stuff of Goop, smoothie start-ups, thalassotherapy spas. It’s Reich shorn of politics, his rebarbative prose, his jarring charisma, his concussive energy. Reich ohne Reich.

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for the Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.