Charity Scribner

Charity Scribner

The most famous German novel you’ve never heard of receives its first full English translation.

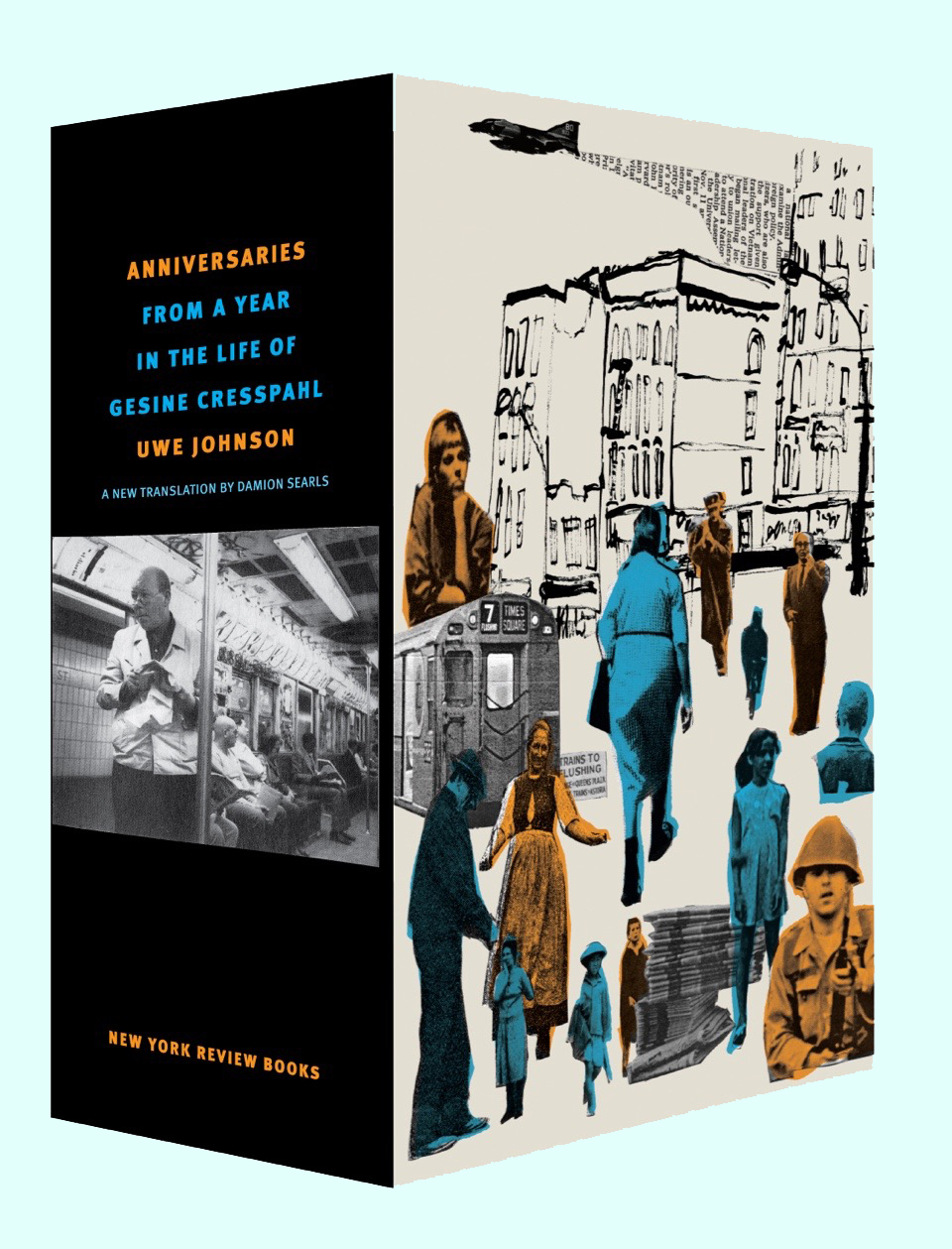

Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl, by Uwe Johnson, translated by Damion Searls, NYRB Classics, 1,668 pages, $39.95

• • •

Many consider Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries to be the most important German novel of the postwar period. Conceived in New York in the mid-1960s and set there around the year 1968, the multi-volume work reflects on the global political antagonisms of that time and relates them to the emergence of fascism in Europe in the 1930s. When the first volumes of Anniversaries came out with the Suhrkamp Verlag in the early 1970s, they quickly found a receptive audience. Hannah Arendt called the novel “a masterpiece,” and critics have put it on par with other great books of European modernity, like Proust’s In Search of Lost Time and Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. Anniversaries, which was completed in 1983, transcended literary circles. It was discussed by artists, journalists, and historians, and, together with works like Peter Weiss’s The Aesthetics of Resistance and Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde, became required reading for intellectuals and activists on the left. To date, the work has not gone out of print.

NYRB Classics has just released an unabridged edition of Anniversaries, newly translated by Damion Searls. Weighing in at 4.9 pounds, the 1,668-page novel is packaged as a boxed set of two volumes, not to be sold separately. The first English translations of Anniversaries, which appeared in 1975 and 1987, were published by Harcourt, Brace, the house that employed Johnson as a German-language textbook editor in their New York offices in 1966 and helped subsidize him when he began writing the novel. Most copies from these print runs went to university libraries. If the initial English-language reception, then, was largely academic, this time around Anniversaries is being pitched to a new—and broader—generation of readers. 2018 is the fiftieth anniversary of 1968, the year of popular uprising, targeted assassinations, and criminal military invasions. The reappearance of Johnson’s work this fall asks us to reconsider the stakes of literary fiction within our current political conditions.

The book’s German title is Jahrestage, or literally “days of the year.” Each of its central chapters marks a single day in the life of the protagonist, Gesine Cresspahl, from August 20, 1967, to August 20, 1968. The calendar imposes a rigorous, almost mathematical structure on the novel. The character Gesine was born in 1933, when Hitler first came to power, and emigrated from eastern Germany to New York in 1961, shortly before the Berlin Wall went up. A thirty-four-year-old single mother, she works as a translator at an international bank and becomes a constant reader of the New York Times. Gesine’s engagement with the paper serves as a platform for the novel’s intersecting temporalities and narratives: through it Johnson manages to tabulate current events and interleave them with reflections on German history. The escalating war in Vietnam, riots of racialized violence in American cities, the Prague Spring—these accounts become departure points for chronicling a shattered past that Gesine can’t leave behind.

Johnson wants us to know that he can’t forget this history, either. His biography and left-critical worldview correspond closely to those of his protagonist. Johnson writes himself into the novel, as a recurrent interlocutor with Gesine, and the characters’ two voices resonate together in a way that both prefigures and surpasses contemporary experiments in autofiction. Karl Ove Knausgaard probably read Anniversaries before writing the six books of My Struggle. Rachel Cusk would have much to learn from it now.

Reckoning with the past is a problem for Johnson, as an author, and that is evident in both the original version of Jahrestage and the attempts to translate the novel into English. Johnson oversaw the production of the book’s first translation in the 1970s and agreed to omit substantial portions of the text, but the deletions removed crucial contexts of German history and thinking. Eliminated, for example, is a passage in which Gesine recounts the shock imparted by a photograph of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, printed in a Lübeck newspaper after the war. “The effect has not ceased to this day,” she observes. “It affected me as an individual: I am the child of a father who knew about the systematic murder of the Jews. It affected my group: I may have been twelve years old at the time, but I belong to a national group that massacred an excessive number of members of another group.”

This passage is restored in the 2018 translation, but Anniversaries is still troubled by other blind spots, for example, Johnson’s allusion to Paul Celan’s “Death Fugue.” This poem, which Celan wrote in German after his parents perished in a Nazi internment camp in Romania in 1942, has become a part of postwar Germany’s literary canon. “Death Fugue” was anthologized in textbooks; it was read aloud at the Bundestag to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Kristallnacht. In Anniversaries, Gesine, a gentile, invokes “Death Fugue” in an exchange she imagines with her mother, who committed suicide. With this move, Johnson risks collapsing her single death into the incalculable tragedy of the Holocaust, perpetrated against Jews by the German nation.

Anniversaries has generated a dynamic body of criticism. Some have warned against a canonization of the work, which Johnson might have bid for in his precarious invocation of “Death Fugue” as an intertext. But, at the same time, the novel is a labor of memory. As he looks to the past, Johnson describes the absences that follow genocide—the voids of language and culture. Anniversaries also opens up new lines of inquiry that lead from the 1960s and up to our present day. We could compare the novel to the work of Hanne Darboven, the German conceptual artist whose serial drawings in the 1970s demonstrated the dialectics between writing and time. Darboven and Johnson both lived in New York City from 1966–68. How does the minimalism of Darboven’s Schreibzeit project relate to the maximal dimensions of Johnson’s epic novel? Through different means, Darboven and Johnson both ask about the adequacy of the German language to express truth in the aftermath of atrocity.

Besides aesthetic questions, Anniversaries also raises doubt in the order of politics. Johnson underscores the continuities of corruption and crisis that connect Germany to America. It remains for us to consider what Johnson’s protracted experiments in life writing have to say about the rise of authoritarian power in the twentieth century—or its continued rise today. As Johnson must have realized while writing Anniversaries, 1968 was defined not only by hopes for social justice but also by ethical failures, including the election, in November of that year, of Richard Nixon as US president. Fifty years later, on November 6, 2018, some of those hopes will return, when Americans go to the polls for midterm elections. They have the chance to strike against Donald Trump’s campaign for one-party rule. Like Johnson, the critical minds of today will do their own accounting.

Charity Scribner is an associate professor of comparative literature at the City University of New York. Her most recent book is After the Red Army Faction: Gender, Culture, and Militancy.