Judith Stein

Judith Stein

Co-ops, tin cans, and baby carriages: the Grey Gallery surveys a period of marvelous experimentation.

Danny Lyon, 79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, 1967. Gelatin silver print, 16 × 20 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Magnum Photos.

Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965, Grey Art Gallery, 100 Washington Square East, through April 1, 2017

• • •

In the spring of 1957, the New Yorker art critic Robert Coates broke from his established gallery route of Fifty-Seventh Street “and points north” to venture further afield in search of material. He headed downtown, across the divide of Fourteenth Street, to the cluster of artist-run galleries in and around East Tenth Street. “If you’re game for poking into old hallways and climbing ancient stairs,” Coates tipped his readers, “you will get a fairly good glimpse of what the youngsters who may make the future are doing at the moment.”

Most commercial art dealers weren’t interested in what the kids were doing in 1957. Abstract expressionism was the only postwar American art with market value. But the young Turks downtown were bored by what mattered to their elders and were returning to the figure and experimenting with hybrid art forms. A splendid survey of some two-hundred examples of this largely unmarketable art is on view through April 1 in Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965, an exhibition organized by curator Melissa Rachleff at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery. A passionate researcher, Rachleff documents thirteen artist-initiated spaces and one highly idiosyncratic commercial gallery active during the period of creative chaos prior to the explosion of market interest in contemporary art in the early sixties.

John Cohen, Red Grooms transporting artwork to Reuben Gallery, New York, 1960. Gelatin silver print, 10 × 6 3/4 inches. Image courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs, New York.

Talk about artists taking the art world’s delivery system into their own hands—John Cohen’s photo of Red Grooms sprinting across Third Avenue with a painting wedged into a baby carriage embodies the resourcefulness of a generation that didn’t want to wait until they were gray before their unconventional assemblages, installations, and happenings went out into the world. You’ll know some of the doers in Inventing Downtown—Yayoi Kusama, Allan Kaprow, Alex Katz, and Claes Oldenburg, for example—but most will be discoveries.

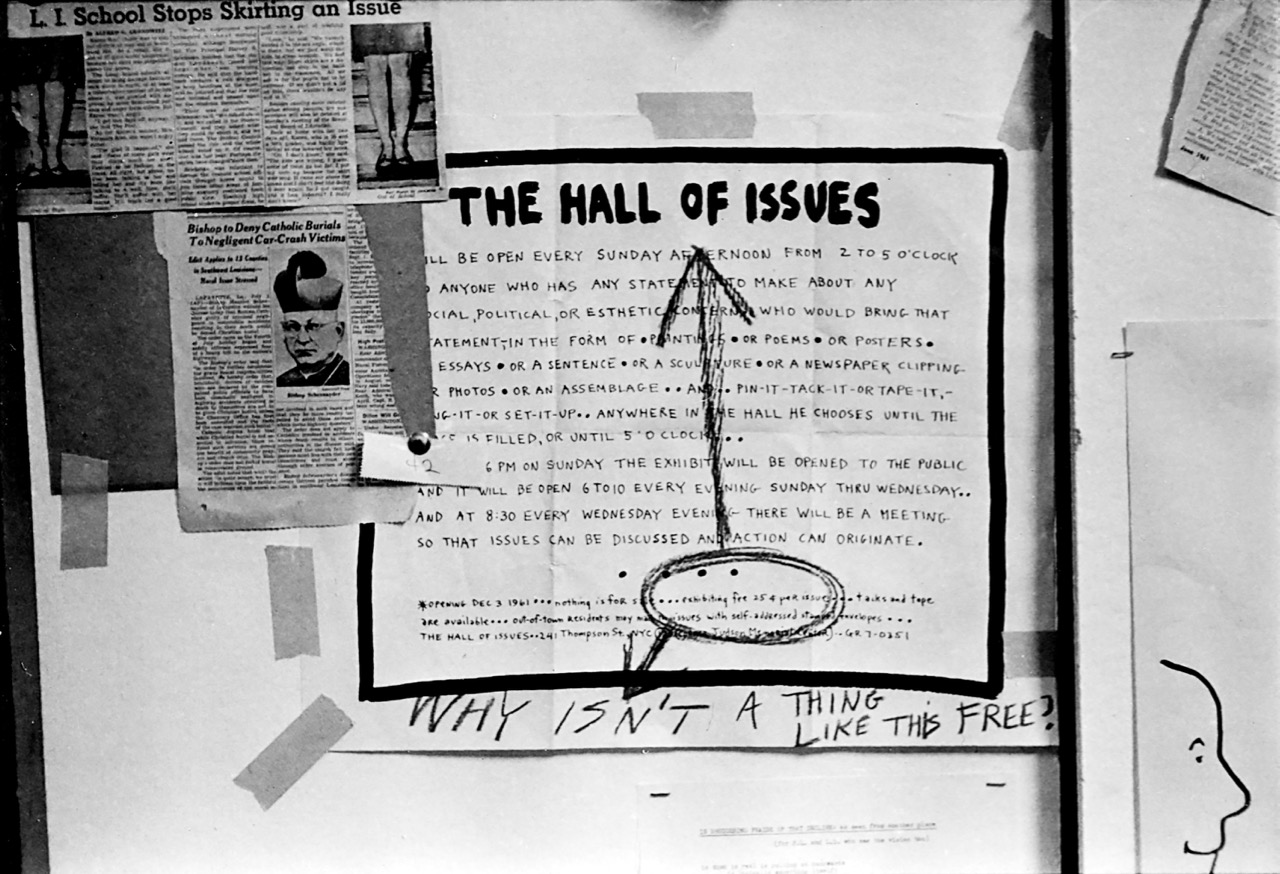

Steven Schapiro, Graffiti on announcement for Hall of Issues, Judson Memorial Church, New York, c. 1961. Digital print, printed 2016, 8 × 10 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Words are nearly all we have left of the more ephemeral initiatives. Phyllis Yampolsky’s Hall of Issues at Judson Church, here evoked with photos and flyers, was an open-call exhibition and public program series. It’s present in a section called “Politics as Practice,” one of Rachleff’s five thematic groupings, which also includes Aldo Tambellini’s community-based multimedia space, as well as Spiral Group, a project by fifteen African American artists, Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Emma Amos among them. March Group, another organization concerned with social justice, introduced me to the charismatic painter and organizer Boris Lurie, a Holocaust survivor. Liberty or Lice (1959–60), Lurie’s massive collage on canvas, is a bristling assembly of text, image fragments, and slashes of acidic color.

Mimi Gross, Street Scene, 1958. Oil stick on paper, 11 × 13 7/8 inches. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Jeffrey Sturges.

Figurative art and assemblage predominated at the temporary exhibition spaces Rachleff chronicles under “City as Muse.” The sight of people passing on the street inspired several artists, perhaps none more memorably than Mimi Gross, whose brilliantly colored oil-stick sidewalk scenes (1958) deserve to be better known. Artists mined the city for subjects and art supplies. Dan Flavin, pre-neon, devised a delightful relief portrait of Apollinaire (1959–60) with a flattened tin can that puns on the shape of the poet’s bandaged head. “Every time you turned a corner,” said Happenings pioneer Jim Dine, “you’d see in the next trash can some wonderful piece of sculpture.”

Stills and videos interspersed in the Grey galleries provide at best a deracinated record of Happenings, events often infused with the épater spirit of the preceding century. In Snapshots from the City (1960), Oldenburg startled his audience by ushering them into a pitch-black room and blinking the lights on and off thirty-two times for a dramatic, low-tech strobe effect. People who attended Robert Whitman’s Duet for a Small Smell (1960) would not have forgotten its noxious sulfuric odors.

The longest-lasting of the artist-run galleries were cooperatives that elected members and shared expenses. Of the many such spaces that clustered in and around Tenth Street, Rachleff highlights three with distinct cultural visions: Tanager and Hansa opened in 1952, Brata five years later. The delightfully inventive sculptor Jean Follett was one of Hansa’s twelve founders, as was her then-partner Richard Stankiewicz. By the late fifties, each had work in New York museums. But Follett’s early success stagnated after fire destroyed her art in storage in the early sixties. She’s represented here by Many-Headed Creature (1958), a fanciful relief of casters, coils, and switches owned by MoMA, which hasn’t had it out on view in decades.

For many co-op artists, the opportunity to show was an end in itself; for others it was a hoped-for stepping stone to recognition. Hansa moved up to Central Park South in 1954, to be closer to the commercial center of Fifty-Seventh Street. But selective acclaim eroded its fractious camaraderie. The gallery folded in 1959, not long after dealer Eleanor Ward took on Stankiewicz, one of the minority of those in Inventing Downtown who attracted and sustained art historical attention. “The commercial success of some of its artists ultimately ended up excluding and marginalizing many others,” Rachleff observes in the catalogue, speaking not of Hansa but of the anomalous Green Gallery, located on Fifty-Seventh Street from 1960–65.

Green is the only tenant in Rachleff’s final section, “Defining Downtown,” installed in the lower-ceilinged spaces downstairs at the Grey. You’ll find some of the same artists here and upstairs: Green’s director Richard Bellamy was an aficionado of the artist-run spaces. Rachleff explains that she included Green in Inventing Downtown because it “brought the downtown uptown.” It’s a phrase I too used in Eye of the Sixties, my 2016 biography of Bellamy published while Rachleff’s comprehensive treasure of an exhibition catalogue was in press. Both publications argue for a fresh appraisal of an era long hurried past on the way to the enshrinement of pop and minimalism as the next major art movements after abstract expressionism.

That said, I find Rachleff’s inclusion of Green, a commercial gallery, problematic, and her assertion incorrect that the program created by Bellamy and his colorful and complex silent backer, collector Robert C. Scull, “resulted in the narrowing of aesthetic possibilities,” as she puts it in the large-format handout. It’s a truism that every choice precludes others. Bellamy and Scull were no more the hands that shifted the art world’s gears than was Time’s cultural scout Rosalind Constable; in 1960 uptown dealer Martha Jackson took Constable’s advice and showed many of the “terrible children,” in the affectionate description of critic Jill Johnston, who made “baffling noncommercial commodities.” Although Bellamy’s cultural authority was unrivaled, he reflected—not triggered—the zeitgeist shift of the early sixties.

Few can detect change as it’s happening. That’s why lines penciled on door jams reveal children’s growth spurts only after the fact. “There is a difference [between] real time versus historical time,” Mimi Gross commented in the catalogue. “Real time has nuances you may not notice but they’re in front of your nose.” Inventing Downtown brings us back to the future glimpsed by The New Yorker’s Coates, to take the measure of what Rachleff describes as the “sensibility of experimentation” that for nearly a decade flowered downtown uncontrolled by the market. It is the intangibility of passing time that is at the heart of Inventing Downtown.

Judith Stein is a writer and curator specializing in postwar American art. Her biography, Eye of the Sixties, Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Modern Art (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2016), earned an Athenaeum Literary Award. Her exhibitions include The Figurative Fifties: New York Figurative Expressionism, and I Tell My Heart, The Art of Horace Pippin, shown at the Metropolitan Museum. A longtime contributor to Art in America, she is a former arts reviewer for NPR’s Fresh Air. She is the recipient of a Pew Fellowship in the Arts in literary nonfiction, a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, and a Lannan Residency Fellowship, Marfa, TX.