René Steinke

René Steinke

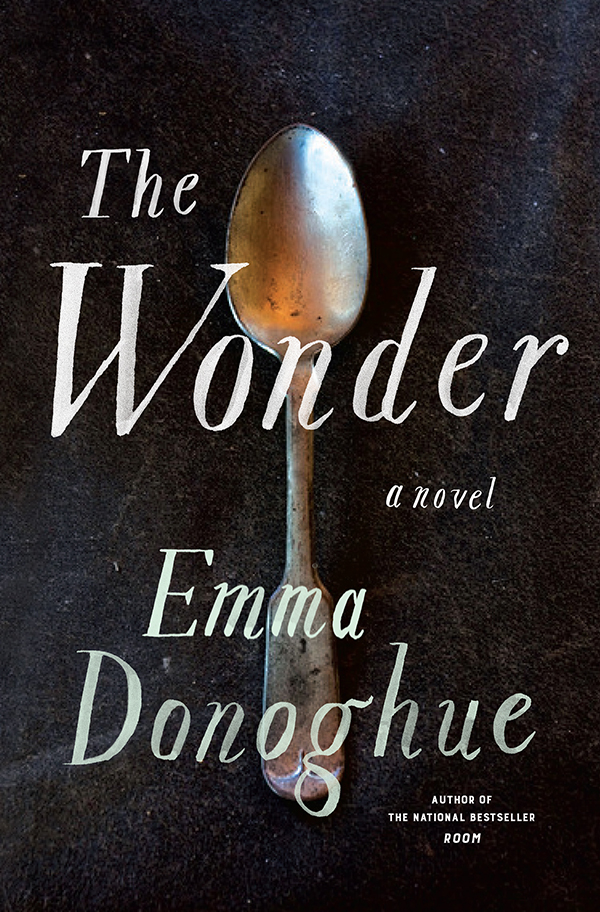

The Wonder, by Emma Donoghue, Little, Brown, 291 pages, $27

• • •

Emma Donoghue is a master at creating charged drama within small spaces. In her 2010 novel Room, a bestseller and finalist for the Man Booker Prize, a mother imprisoned by a madman with her young son invents an entire landscape—and even a kind of cosmology—within four walls. In her absorbing new novel, The Wonder, the room in question belongs to Anna O’Donnell, an eleven-year-old girl said not to have eaten for four months. Here again, Donoghue sets remarkable scenes inside a narrow space to explore how belief comes to shape—for good or ill—the identity of a child.

Anna is a “fasting girl,” one of the young women in centuries past who refused to eat, some of them claiming to live purely on God’s sustenance. The fasting girl was sometimes hailed as a religious model, or even a miracle, but at what cost to her? The Wonder draws from this history and imaginatively bears witness to Anna’s fast, which is not only tolerated, but celebrated by her strict Catholic family.

The story is told from the viewpoint of Lib, a practical British nurse charged with overseeing Anna. Lib has no patience for the miraculous. Trained by Florence Nightingale, she has remade herself as one of the “new nurses” with a rare basic knowledge of medicine. Lib has been called to a rural village in Ireland, where people leave bowls of milk out at night for the fairies, tie rags to a tree in order to cure bodily ills, and nearly everyone is Catholic.

This is 1859, a few years after the potato famine, during which about a million people died from disease and starvation. Insisting that she is nourished by “manna from heaven,” Anna has been touted by the locals as “an extraordinary wonder.” She has attracted the attention of newspapers and visitors who come from as far away as America to gawk at her or ask for her blessing (and make donations to the coffers of the village parish). A “committee” of local men has enlisted Lib, along with a nun, to keep vigil over the girl: to verify that Anna is indeed living without earthly food, or to discover the hoax.

Anna is first described sitting in a chair “as if listening to some private music.” Despite the grotesque results of her starvation—a “downy fuzz” all over her body, papery skin and bald spots on her head, legs so swollen she wears her dead brother’s old boots—she is also resilient and charming. Her faith seems to have helped her endure poverty, and within her limited means, religion provides access to ideas and beauty.

Lib and Anna spend hours in the small quarters of Anna’s sickroom. At first, Lib is convinced that Anna will easily be found out, that she is “a cheat of the deepest dye,” but even when Lib searches the girl’s private chest, or inside a china candlestick, she finds no evidence of hidden food.

It’s a brilliant move to filter the story through Lib, who (like many contemporary readers) relies on science, not religion. “Science was the most magical force Lib knew,” we’re told. As one of the few professional women of her time, reason is where Lib finds her authority. But as much as she prides herself on this, she is also hobbled by prejudice—against the poor, the Irish (who were “notorious for neglecting the niceties,” and might be prone to “hairiness”), and especially Catholicism (“pious gymcrackery”).

Told in spare, lucid prose, the narrative relies more on dialogue than interior reflection—fitting for Lib’s position as the outsider searching for evidence. Donoghue’s approach transforms Anna’s private prayers and interpretation of doctrine into clues to the compelling mystery of her fast. The storytelling is especially nimble in the tense, intimate moments between Lib and Anna—when they discuss the death of Anna’s brother, the physical symptoms of starvation, or God’s silence.

Lib may be liberated from religiosity by her scientific worldview, but it also limits her ability to see. Before Lib came to monitor Anna, she had been taught to guard against “attachments in any form and root them out,” to care for her patients in the most clinical way. However, the spiritual crisis that threatens Anna’s health resists detection by medical observation—daily notations of pulse, respiratory rate, and body temperature don’t help one to grapple with ideas outside the material world. Lib begins to worry that she might become complicit in the girl’s death, along with the parents, the priest, the nun, and the doctor—all of them just watching and waiting.

Ironically, it’s Anna, the patient, who first draws out Lib’s confidences. Only after Lib has confessed her own catastrophic losses does she begin to understand how Anna’s imagination works. (And Anna is such a winning character, it’s difficult not to hope that she is a miracle, surviving on a few sips of water and air.) Anna’s fasting might even be seen as an attempt to quietly subvert the same Catholicism that oppresses her: “To fast was to hold fast to emptiness, to say no and no and no again.” Fasting allows Anna to take control of her body, to consecrate the same flesh she’s been shamed into hating. But it’s also a very dangerous trap.

Eventually, Lib admits that despite Anna’s wasted body, she seems “lit up with a secret joy.” At this point, the story turns away from interrogation to the seemingly impossible mission of saving Anna’s life. Lib finally realizes, “This fast, it’s Anna’s rock. Her daily task, her vocation.” No reason or medicine will keep her from it. In an especially moving passage, Lib, out of desperation, finds herself praying to the God she still doesn’t believe in.

Donoghue writes with exceptional appeal about the often uncomfortable subject of religious belief, which, she says in a piece in The Guardian, “is the most embarrassing subject to talk about in detail. You sound pompous or confused as soon as you open your mouth.” In The Wonder, though, such conversation reveals the radiant complexity of human limitation and longing.

René Steinke is a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow. Her most recent novel, Friendswood (Riverhead), was shortlisted for the St. Francis Literary Prize and was named one of NPR’s Great Reads. Her previous novel, Holy Skirts, an imaginative retelling of the life of the artist and provocateur Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, was a finalist for the National Book Award. She is currently the director of the MFA program in Creative Writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University. She lives in Brooklyn.