Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Domestic bliss has gone amiss in two twentieth-century novellas by

Natalia Ginzburg and Rachel Ingalls.

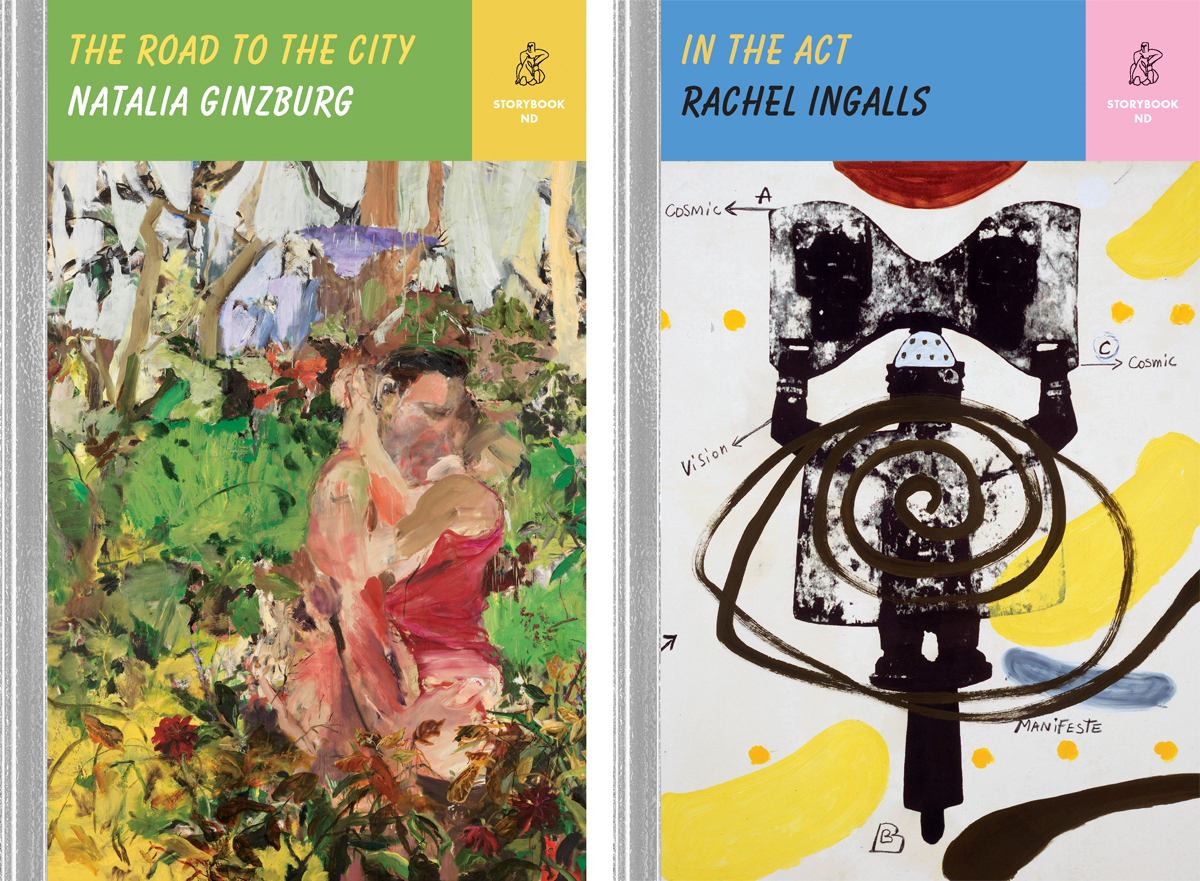

The Road to the City, by Natalia Ginzburg, translated by Gini Alhadeff, New Directions, 94 pages, $17.95, and In the Act, by Rachel Ingalls, New Directions, 61 pages, $17.95; both part of the Storybook ND series, created and curated by Gini Alhadeff

• • •

Ann Quin, Kathleen Collins, Eileen Chang, Zora Neale Hurston, Natalia Ginzburg, Rachel Ingalls . . . recent literary headlines have declared these twentieth-century greats “revived” and “rediscovered.” And good thing—I love these authors. To the feminist writer of the twenty-first century, their “revival” is a reminder that at least two specters have long haunted the novel: one, the conviction that the previous generation wrote them better; and two, heterosexual doom.

I might not have thought to read Italian memoirist Natalia Ginzburg (1916–91), wry chronicler of family life and politics in Mussolini’s Italy, and American writer Rachel Ingalls (1940–2019), master of surreal feminist novellas, together. While Ingalls is fantastical and satirical, more single-minded in her critique of patriarchy, Ginzburg’s understated protest is powered by narrators’ faux naivete of power structures. New Directions makes a persuasive case for a pairing, however, with the simultaneous publication of the novellas The Road to the City (1942) and In the Act (1987), both part of their new Storybook ND series. A shared genius for terse tragicomedy is on display: behold the reactive potential of a mid-century woman in domestic captivity, distilled into less than one hundred pages.

The youngest of five, Ginzburg writes like someone used to being interrupted, precisely observing daily life with a sibling’s affectionate revenge. Her work is marked by a kind of atmospheric pressure. Social expectations press in on all sides, and it’s her conviction in the personal, the detail, that keeps private experience from collapsing under them. The autobiographical, anti-fascist Family Lexicon (1963), for example, translated by Jenny McPhee, reverberates with bespoke vocabulary, as her father directs his favorite insults (“Nitwittery!” “Jackass!”) and solecisms toward his errant children and Mussolini indiscriminately. As the novel progresses, fascism’s erasure of the individual is counteracted by a record of idiosyncrasy.

The Road to the City, Ginzburg’s first book, translated for this edition by Gini Alhadeff, is more propulsive than Lexicon, and it’s patriarchy, rather than fascism, that registers barometrically on every page. “When I started to write [it],” Ginzburg shares in an accompanying afterword, “. . . I wanted every sentence to be like a slap or the lash of a whip.” Our unnamed narrator is seventeen, the younger daughter in a chaotic, cash-strapped household, who wishes (so she thinks) to get married. A few pages later, she’s attracted the admiration of two different suitors, and a few pages after that, she’s pregnant—though not yet hitched. With understated doom, she wonders: “What will I do now?”

The culprit is Giulio, the son of the village doctor, who tries to avoid tying the knot. Despite the disastrous consequences his evasion poses for the protagonist, one almost hopes he succeeds; her true love is clearly Nini, a childhood friend and factory worker. They meet every day after his shift until the pregnant narrator’s parents start keeping her prisoner at home. When Nini finally discovers her with child, confined to bed for morning sickness and shame, the would-be couple’s heartbreak arrives as another lash of the whip. Accusing the narrator of having enjoyed making him suffer, Nini looks at her “with a mean glint in his eyes. ‘You’ve succeeded,’ he said.”

The sense of tragedy lies in the speed—too much happens too irreversibly, too fast. Early on, when Giulio lures the narrator deep into the woods, she tries to stall, claiming exhaustion and thirst, but the doctor’s son has come prepared. Producing a bottle of wine, he “made me drink some, till I lay down in the grass dazed and what I’d been expecting happened.” The entire seduction takes a paragraph. Later, feuds erupt and settle in a few sentences. An argument with the urbane older sister, who lives “in the city,” about losing one’s virginity is introduced and then resolved in a phrase: “the next day I went into the city just to make up with her, but when I got there she had calmed down and was trying on a new dance outfit.”

What in other writers might seem like an affected austerity here produces the urgency of trying to stop someone from walking into moving traffic. If the narrator speeds laconically along, seemingly repressing her emotional responses, it’s because that’s the nature of adolescent psychology, where profound loss finds only oblique expression. The novel harnesses its power through all that’s left unsaid. At the opening, she’s ecstatic over a new, light-blue dress she cuts and sews herself; later, bedridden, she proclaims with crushing simplicity, “I no longer had any interest in clothes.”

Ingalls (whose major influences were playwrights, especially Shakespeare and Ibsen) is better known than Ginzburg for leveraging tragic arcs, with the cult classic Mrs. Caliban (1982) tracing an especially swift, predestined demise. A grieving housewife (she’s recovering from a miscarriage) trapped at home with her brutish, neglectful husband falls in love with a frogman who’s escaped from a local laboratory. The unclassifiable speculative streak can make a summary feel ridiculous, yet in Ingalls’s hands, the improbable, if doomed, interspecies affair articulates an emotional and sexual awakening more convincing than many traditional works of science fiction or literary realism.

In the Act tilts more toward the slapstick, and doesn’t quite measure up to Caliban’s originality in its skewering of 1950s-era gender clichés. Nevertheless, fans of Caliban’s more uproarious moments won’t be disappointed. Protagonist Helen is exiled from her home twice a week so her scientist husband, Edgar, can work in his attic laboratory in “complete freedom.” Once allowed back home, she’s not to open the attic door. As in the Bluebeard tale, she does, discovering that her husband has invented himself a robotic sex doll. She disposes of her marital rival in a public locker at the train station, setting off a chain of risible mishaps when a thief steals the robot woman and parades her around as his IRL girlfriend. What follows is a classic skit of marital one-upmanship, as Helen plots her revenge—even demanding Edgar produce a male doll for her own pleasure—and her husband desperately tries to win the original back. The punchline, though foreseeable, is no less satisfying when it arrives, with the robots ultimately enjoying more sex (and relationship power) than the humans.

Edgar is the kind of absurdly awful pedant who counts how many grapefruit segments Helen has failed to dislodge from their membranes while preparing his breakfast. The two sons take after him, and though Helen regrets sending them off to boarding school (at their own request), she’s also “probably lucky they were far away. That would have been two more grapefruits she wouldn’t be able to get right.” But as in Caliban, the true comic engine lies in the protagonist’s practiced manipulation of her husband. What at first seems like docile submission is in fact carefully organized war theater. Having forsaken getting angry with Edgar (“it did no good”), Helen instead adopts the “fudgy, forgiving drone she’d found effective with the children: enough of that sound and . . . people would agree to anything.”

I read these novels delightedly, in a single sitting, as New Directions meant me to. In the afterglow, however, I couldn’t stave off the sobriety of comparing the worlds they depict to mine. The unfettered misogyny Ingalls and Ginzburg subvert is rigid, predictable, inconsistently retired. Its dominion seems to have slipped here, doubled down there. How to write about the not-yet ghost, the specter still dying but definitely not dead? Of course there’s a revival of Ingalls, of Ginzburg. The rules are scrambled, but the game is still on.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens is the author of the novels The Exhibition of Persephone Q and The Visitors. Her debut story collection, Ghost Pains, is forthcoming from And Other Stories in March 2024.