Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Dystopia and cyborg chickens: the technoparanoiac worlds of the artist’s late works.

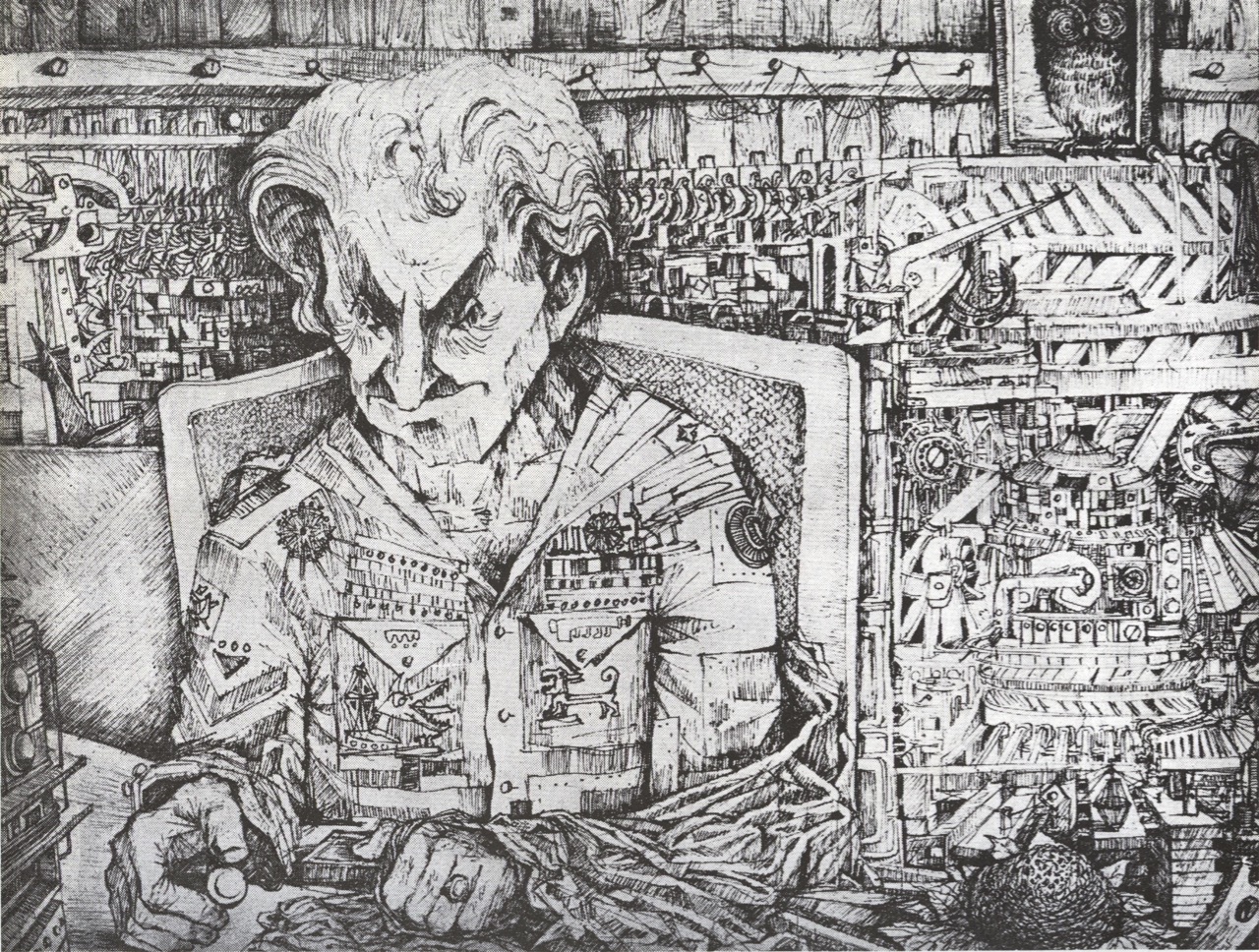

Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, A Body Falling from the Sky, 1964. Pen, watercolor, and gouache on board, 24.4 × 27.2 inches. Image reproduced from Sobhi al-Shorouny, Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, 2007.

Examples of work by Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, including his cyborg bird, are available on the Barjeel Foundation website.

• • •

Editor’s note: Given restrictions on visiting museum and gallery exhibitions in person during the coronavirus pandemic, we have offered our contributors the option to reflect on an artwork or body of work that is particularly significant to them and easily viewed online.

• • •

Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar was one painter in a trainful of artists selected in 1963 to visit the Aswan Dam, during its Soviet-funded construction in the south of Egypt. The trip was sponsored by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s revolutionary regime, which wanted Egypt’s finest to immortalize the president’s dazzling technological triumph over nature. By then, Gazzar certainly was considered one of the finest, if not the preeminent, painter of the new postcolonial state. As was to be expected, his resulting painting, the award-winning The High Dam (1964), was immediately celebrated by officials as an icon of the Nasserist era. But the Aswan experience also provoked a fantastical body of work that the artist largely kept private. His first India ink drafts of the scaffolds and cranes and pipes and machineries he saw there started out as sober visual chronicles of a sublime work site, but soon that sublimity would explode in his vision. Those machineries took on lives of their own, crawling spiderlike across the page and melding with impoverished human and animal forms. Then, a UFO alights to blast this whole invented world down (A Body Falling from the Sky, 1964); and now look, three wrinkled, pastel-colored alien beasts have materialized, whirling their eyes as they crouch beneath transparent membranes in a landscape punctuated by inexplicable equations (Falling Objects, 1964). Though Gazzar had employed futuristic imagery prior to Aswan, the style of these compositions is a world apart: they are claustrophobically covered with inscrutable details, webbed with a multitude of agonized lines, drawn by a cramped and manic hand.

Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, Falling Objects, 1964. Image reproduced from Sobhi al-Shorouny, Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, 2007.

Art historian Sobhi al-Sharouny, long the artist’s most cited interlocutor (and author of the only monograph in English), designated the years from 1963–66 as Gazzar’s “mechanical period,” the last in a trajectory that scholars have tended to explain as ordered by clearly delineated phases, preceded by Surrealist, folk, and social realist. Sharouny and Gazzar’s other early champions (including Lebanese art critic Aimé Azar and French academic Alain Roussillon) found the paranoiac aspect and dystopian vibrations of these drawings and paintings (many of which today are lost or squirreled away in private collections) to be an aberrant distraction from Gazzar’s better-known folkloric scenes of everyday life in downtown Cairo, or depictions of social injustice under monarchic rule. Sharouny saw in the mechanical period Gazzar’s fearful portent that he would soon die, which he did, in 1966, at age forty, reportedly from rheumatic fever that had attacked his heart. Perhaps these works were indeed anxious symptoms of his reckoning with mortality. But they might also augur another type of ruin: the desolation wrought when those in power, blindly striving to achieve their political program, end up banefully tromping on anything in the way.

Gazzar has often been blithely characterized as a state painter whose works agitated for the political commitments of the Nasser regime. Starting from his youthful student days in the Contemporary Art Group—a circle headed by the charismatic Youssef Amin, who taught his young acolytes about things like the Mexican muralists and John Dewey’s philosophy of art—Gazzar evinced a belief that art should drive social progress. He signed his name to a manifesto that declared: “Contemporary art is a tool of attack and knowledge. Art has become its own master, and a leader of people’s consciousness, after it had long served hidden ambitions or been used as a tool for diversion and entertainment.” It would seem he was also targeting the people’s consciousness in his later pictures, which canonize important events like Nasser’s participation in the 1955 Afro-Asian conference, and his issuing of the National Charter, the foundational policy document of his socialist vision. But there were signs of ambivalence and critique in these scenes, such as in Construction of the Suez Canal (1965), into which Gazzzar sneaked depictions of violence that were likely allusions to the deadly work conditions at the Aswan Dam site. And in private, he was simultaneously scribbling into existence those technoparanoiac worlds of machines colonizing body and mind, which reveal the full extent of his trepidation about Nasser’s modernist dream.

Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, The Laboratory, 1964. Image reproduced from Sobhi al-Shorouny, Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, 2007.

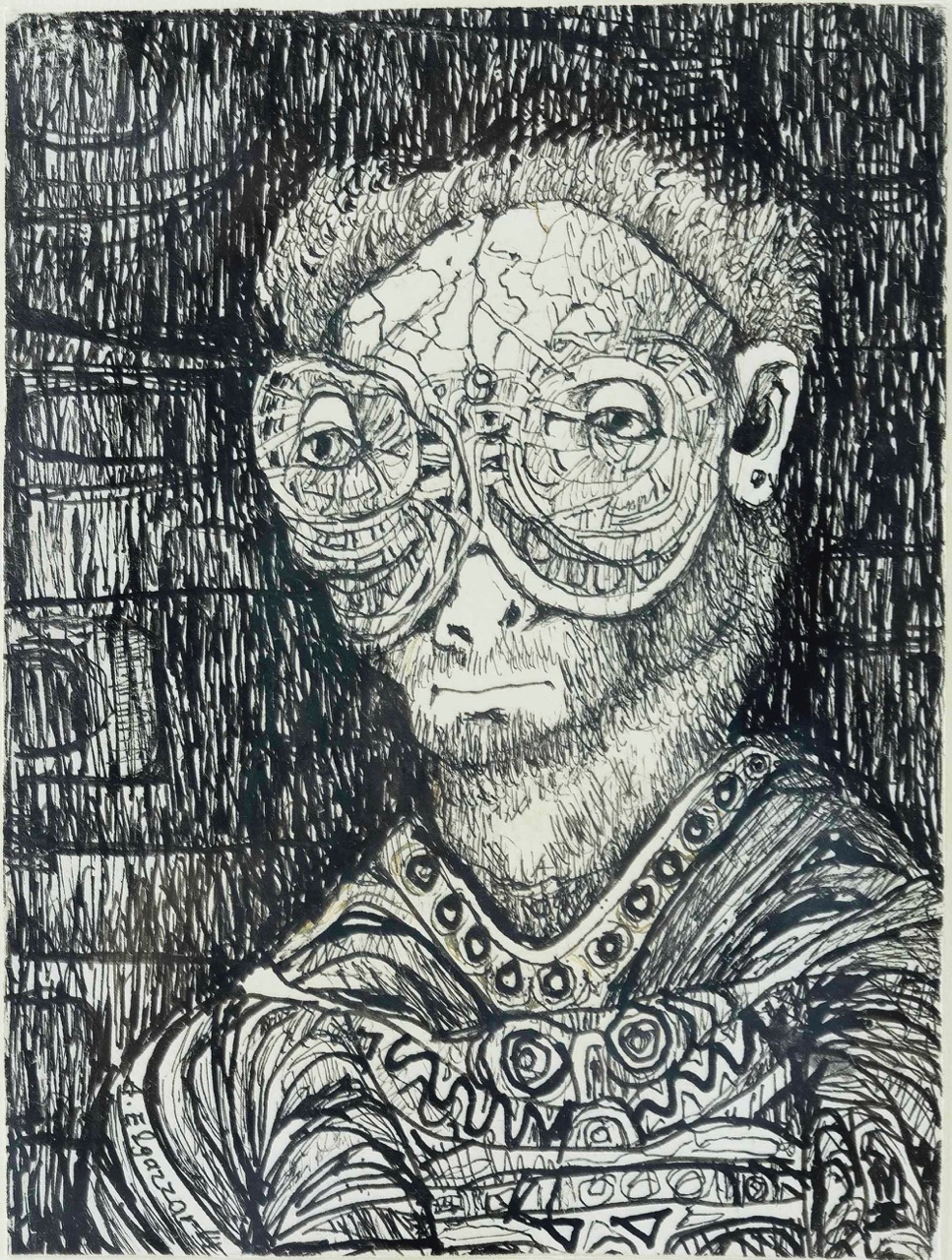

Gazzar, who was something of a Sunday scientist, was on the one hand enchanted by the popular imagery of science fiction, then a burgeoning genre in Egypt. In these late works one finds wild-haired lab technicians and cyborg chickens, leering robots and snaggletoothed beasts of supernatural mien. He even wrote a short story that imagined a little devil and angel tallying up a soul’s good and evil deeds on tiny computers, and which pictured the souls of the dead gliding through cosmic worm holes. But what’s more, images like From the Cosmos or Man and Mechanics (1964)—which shows an anemic, semi-human visage whose forehead is cracking apart, whose suffering eyes have been taken over by some sort of fantastic machine—could also be read as a perverse interpretation of the current discourse about forging a modern Egyptian “man of metal” who would pull the nation into a more advanced future. Omnia el-Shakry has written, for example, of a government experiment in which officials screened agrarian laborers to select the healthiest, most beautiful, and most intelligent men and women, then sent these specimens to live in a desert settlement where everyone wore the same uniform and sang patriotic songs in unison in the evenings. The regime’s attempt to mold and propagate the perfect citizen also revived the subject of eugenics in official conversations. The forces of “progress” mold Gazzar’s subjects, too, but they do not become shiny citizens of the future; instead they emerge erratic, corrupted, and strange.

Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, From the Cosmos or Man and Mechanics, 1964. Ink on paper, 6 × 4.3 inches. Image courtesy Christies.

Today, Gazzar is Egypt’s best-known modern painter, the most studied and written about, the most valuable to collect, the most likely to be counterfeited. Renewed interest in his oeuvre started seriously percolating after the eighteen days of January 2011, which makes sense, the painter of the earlier revolution being resurrected in the wake of a second one. In the summer of 2011, the freshly installed director of Cairo’s Museum of Modern Art brought several long-forgotten Gazzar paintings out from storage and finally put them on display; in the spring of 2012, she also spearheaded an exhibition of his works at the museum’s temporary exhibitions gallery, many of them previously unseen. When I myself was researching Gazzar around this time, the apartment of his widow Laila was frequented by American and European scholars and curators who accepted her kind hospitality as they combed through her archives and personal collection in search of the not-yet-published. Gazzar’s work has been included in recent large-scale traveling exhibitions, like Surrealism in Egypt: Art et Liberté 1938–1948, which opened at Centre Pompidou in 2016 before going on tour to the UK and Sweden; and this year’s Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s, currently on pause at NYU’s Gray Art Gallery. He’s collected by major foundations and museums around the world, including the Met, which in 2018 acquired his 1951 An Ear of Mud, An Ear of Paste for over half a million dollars (it is now on view in the recently reopened institution). There are reportedly a catalogue raisonné and new monograph in the works.

Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, Chain and Time or Waiting for the End, 1964. India ink on paper, 11 × 14.5 inches. Image reproduced from Sobhi al-Shorouny, Abdel Hadi al-Gazzar, 2007.

Gazzar’s cryptic intergalactic scenes have mostly been footnotes in these recuperations; perhaps they are still considered too ancillary to the rest of his oeuvre to merit serious study. (I have also encountered a petty predisposition among some US scholars to dismiss them as “bad” and “derivative.”) But these pictures, too, deserve our attention. His tattered and monstrously complex robotic bird, his begoggled and vitiated space man, his tremulous alien beasties feel just as anxious nearly sixty years after they were made, as sweeping authoritarian programs in Egypt and around the world are still trying to subjugate the earth and its humans, wrecking both in the process.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.