Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Cuteness, cruelty, dance party: new works from the Thai video artist.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Jaonua: The Nothingness, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Jaonua: The Nothingness & Sanook Dee Museum, Tyler Rollins Fine Art, 529 West Twentieth Street, New York City, through July 28, 2017

• • •

Two loving hands delve into a dog’s luxurious pelt, scratching, smoothing, and scrunching the furry flesh with pleasure. A tiny baby goat quivers and bleats plaintively, stumbling around on knocked knees like a defenseless Disney character. A beautiful, softly lit young couple enjoys happy, bouncy sex.

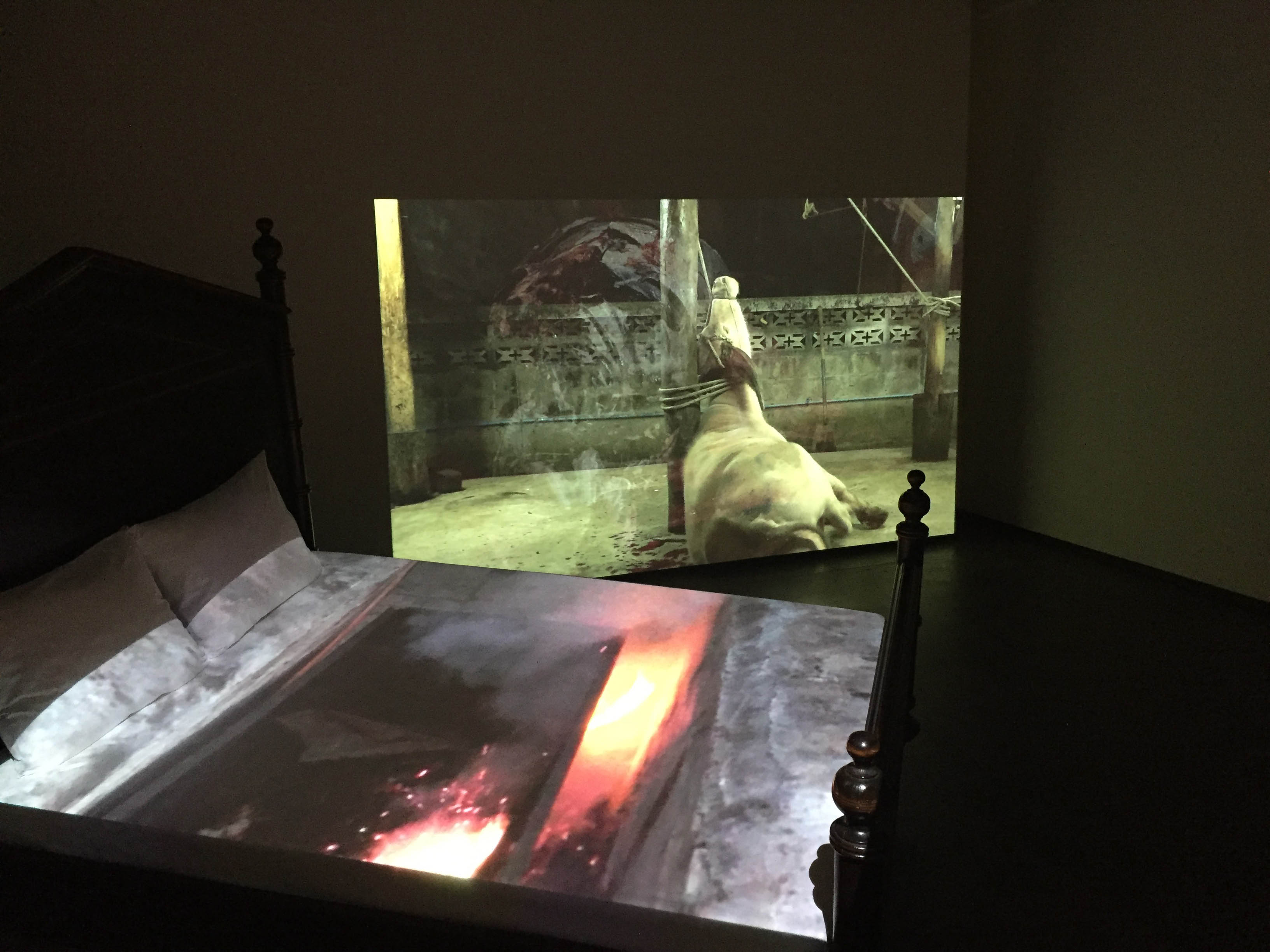

Internationally renowned Thai artist Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s five-channel video installation, Jaonua: The Nothingness (originally commissioned for the 2016 Singapore Biennale and now on view in an “expanded format” at Tyler Rollins) is filled with paroxysms of cuteness and visceral pleasures. In one channel, a truck full of barnyard animals takes a joyride through a quaint village—look how adorably inquisitive the cuddly beasts are! In another, a delightfully entitled little bulldog stands on a table (well, actually a horizontal video monitor playing porn) between an attractive young man and woman, helping them gobble up a meaty meal! The fact that each video is projected onto a domestic item (a fuzzy rug, a half-cocked bed, a comfortingly tacky picture frame) only reinforces the work’s sweetness.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Jaonua: The Nothingness, 2016. Digital print, 31 × 47 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

But that sweetness turns out to be contingent on the moment when the viewer enters the installation—because soon enough, jarring images of extreme cruelty destroy the reverie. That innocent newborn goat is in fact an orphan being ruthlessly rejected by another mother, who head-butts him away every time he comes near. In another scene, we find ourselves in a slaughterhouse, watching a bloodied ox bound to a pole by his neck flip, twist, and groan in an agonizing attempt to escape. (I had to turn away more than once while watching—the images are disturbing enough that a warning was posted at the entrance of the gallery.)

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Jaonua: The Nothingness, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

This push and pull between pleasure and pain is at the core of Jaonua’s mechanics, which pivot on pronounced binaries: tenderness and brutality, eros and death, masculine and feminine. This dynamic is then complicated by the multiple screens: at times, one unifying image seems to flit across each channel, as if the discrete videos were coalescing into a cohesive whole; but in fact, each projection tells a distinct story, and you have to turn your back on one to take in another.

A binary structure also informs the second video work in the exhibition, the less-interesting Sanook Dee Museum (“fun museum”), which is cloistered in a curtained-off black box near the gallery’s entrance and shown on an unassuming video monitor. The premise boils down to confronting Thai villagers with canonical Western artworks—the presumed rubes are brought into a museum setting, where foreigners who perform fluency in contemporary art-speak solicit their commentary on a selection of photographs. The ensuing discussions reveal a predictably humorous disjunction between “art world” and “real world,” to the general amusement of all actors. (Here, the binaries are almost annoyingly obvious: East vs. West, high vs. low culture.)

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Amusement in Sanook Dee Museum, 2017. Digital print, 31 × 47 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

Rasdjarmrearnsook gained notoriety for a series of videos executed in the early 2000s in which she acquired corpses from a medical facility and recorded herself interacting with them in a variety of scenarios: hosting symposia for them on the metaphysical quandaries posed by death, dressing them for a party. These works were shown in international venues from the Venice Biennale to SculptureCenter, where the artist had her first US museum retrospective in 2015. I remember becoming hotly indignant as a grad student when I learned of Teresa Margolles’s contentious work with human remains (which included presenting a dead man’s tongue as a sculptural object), but somehow Rasdjarmrearnsook’s investigations with the dead don’t provoke the same outrage. I’m not sure if my self-righteousness has tempered with age or if it’s something to do with the practice itself; indeed, in the critical literature on Rasdjarmrearnsook, the ethical implications of both the cadaver and slaughterhouse videos are raised only as potential questions, never as outright invective. Granted, her methods of obtaining bodies appear to be cleaner than Margolles’s (in some instances, the Mexican artist is reputed to have badgered indigent family members into letting her use their loved ones’ body parts). But more than that, there’s a seductive lightness and conviviality to Rasdjarmrearnsook’s work, even amid the corpse-students and murdered animals.

The artist draws heavily from Buddhist theology, and her work is often embedded in a critique of Thai socio-cultural norms; it’s densely allusive, and at Tyler Rollins, the printout available at the front desk is a necessary key to tracking the plot points of the multiple videos (if you’re concerned with punctiliously following the narrative). The works will of course be more or less legible according to the viewer’s familiarity with these cultural references, but at least some degree of opacity feels intentional; she often touches on a fundamental impossibility of communication—from vainly exhorting anonymous dead bodies to participate in a discussion on death in The Class I (2005), to lecturing a placid, disaffected group of horses on the Stoics in Jaonua. Even in Sanook Dee Museum, attempts to bridge the cultural divide between the villagers and the artworks are ultimately abandoned in favor of a dance party. These one-sided or unsuccessful dialogues underscore not just the futility of the act of communication itself, but the silliness of what we try to talk about in the first place—ancient Greek philosophy seems comically unimportant when you watch someone trying to explain it to a horse.

Despite these missed connections, Rasdjarmrearnsook’s is not a lonely vision—it’s weirdly optimistic, even happy making. Her work could be read through different frames (art historical, political, religious), but its emotional resonance was what I found most striking. “Cute” is usually a weak, pejorative critical term, but these videos are suffused with an undeniable cuteness that inspires not disdain, but longing for warmth and communion. The attendant images of violence and suffering, as harrowing as they are, exert pressure on our empathetic faculties in a way that achingly evinces a fundamental desire to care and protect, even as we must reckon with an equally fundamental capacity to harm. Human subjects are decentered to settle on an equal horizon with their wordless animal counterparts—and no Harawayian lens is needed here to appreciate the egalitarian, fraternal cosmology that such a move invokes. Rasdjarmrearnsook suggests the possibility of tapping into a primal tenderness in a time when it is deeply needed.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns. From 2011–15, she was the chief curator of Townhouse, a nonprofit contemporary art space in Cairo, Egypt; she was also a founding editor of Mada Masr, Egypt’s premiere platform for independent, progressive journalism. She is a recipient of a 2016 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.