Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

The ecstasy of song and dance in the face of war and upheaval.

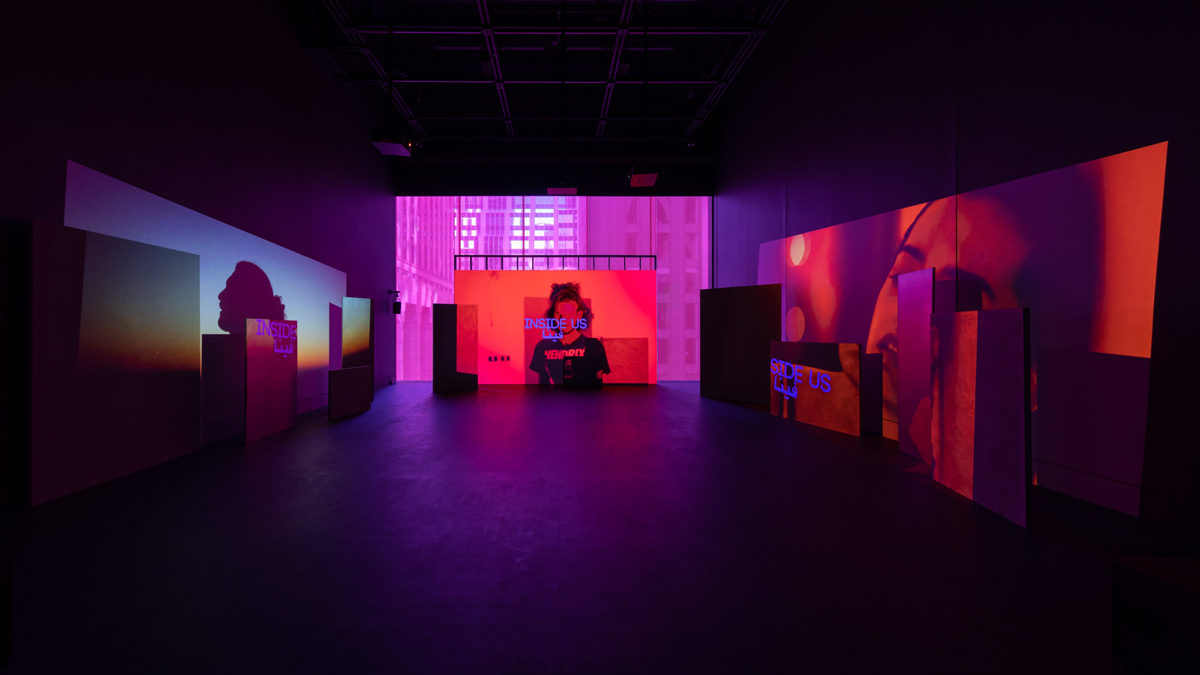

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar. © Museum of Modern Art.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, online here for the Dia Artist Web Project, and curated by Martha Joseph for the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through June 26, 2022. Live performances by Hiro Kone, SCRAAATCH, Muqata’a, and the artists throughout the month of June.

• • •

“The bourgeois and the petite bourgeois spend their time partying,” Roberto Bolaño writes in “Leave Everything, Again,” the first manifesto of the Infrarealist literary movement. “The proletariat doesn’t have a party. Only funerals with rhythm. That’s going to change. The exploited will have a grand party. . . . To intuit it, to consider it certain nights, to invent its edges and humid corners, is to stroke the acid eyes of the new spirit.”

Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas might be intuiting the edges and humid corners of such a party in May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, a nearly decade-long project whose title comes from a line in Bolaño’s text. He penned his manifesto in Mexico City in 1976, after the Tlatelolco Massacre, after Pinochet’s coup. Abou-Rahme and Abbas began collecting the materials for May amnesia in the early 2010s, after the Iraq War “ended” and the Syrian Civil War started, both in 2011; when the Yemeni Civil War began in 2014; when Israel bombarded Gaza that same year, another episode in its decades-long illegal occupation of Palestine, its attempted genocide.

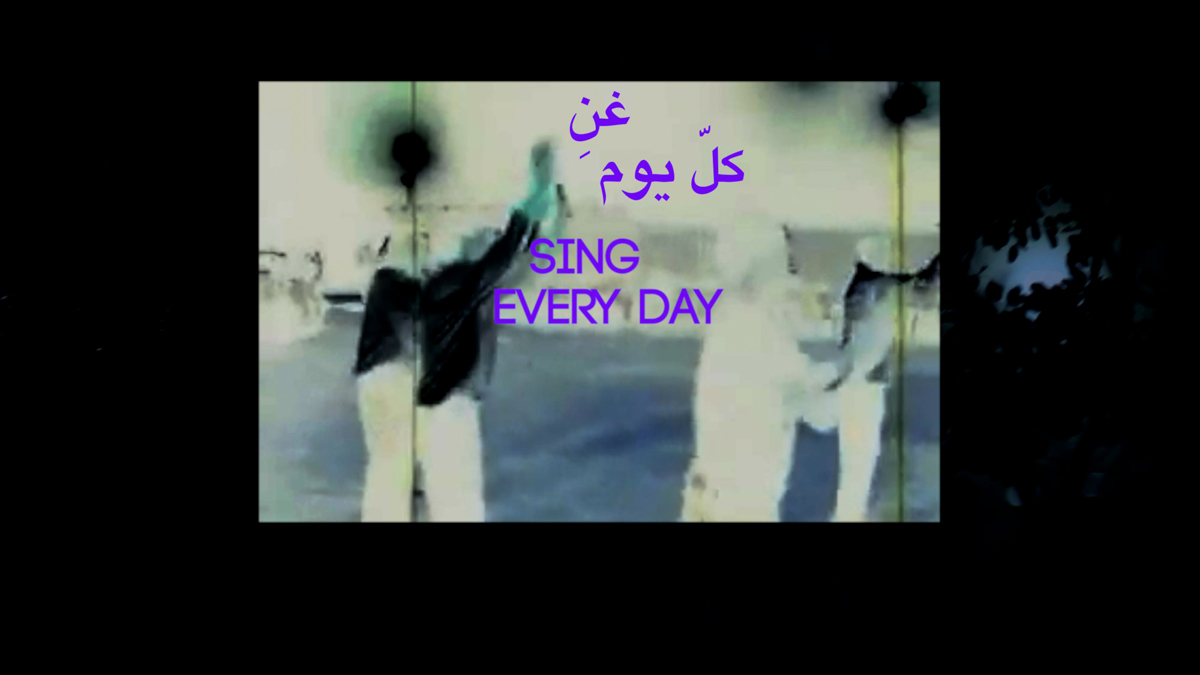

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, still from May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2020–ongoing. Courtesy the artists.

“These are hard times for poetry, some say,” Bolaño writes. “These are hard times for mankind, we say.” Yet it’s especially in hard times, as he knew, that poetry is to be recited, songs to be sung, and parties to be had. Cultural institutions like media outlets and art museums usually sniff for bloodied content when they endeavor to represent such hard times. But the materials Abou-Rahme and Abbas have been collecting are of the ecstatic kind: found online recordings of people they don’t know—from Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Palestine—singing, playing music, dancing, alone in their bedrooms, together at weddings, on a beach, at parties.

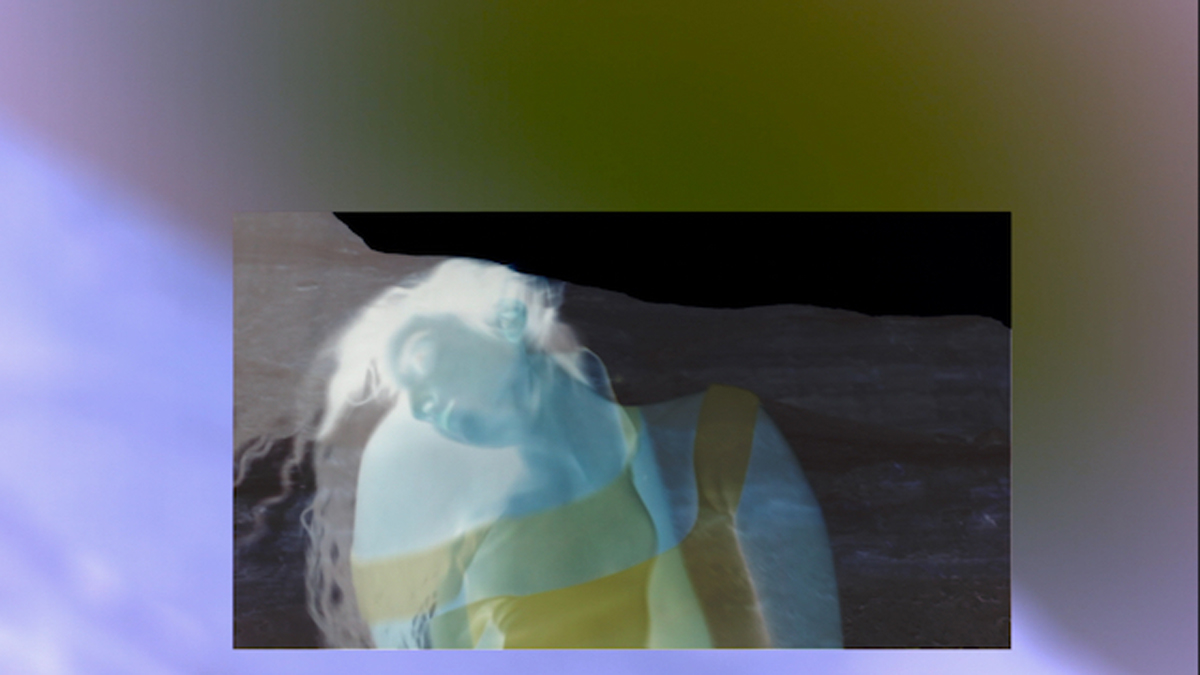

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, still from May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2020–ongoing. Courtesy the artists.

Abou-Rahme and Abbas collaborated with Palestinian dancer Rima Baransai and Ramallah-based electronic musicians Makimakkuk, Haykal, and Julmud to extract gestures, phrases, and melodies from those clips to create new videos of individuals performing simple, repetitive choreography, mingled with imagery of flowers and empty roads, all set to original musical compositions, and in which snippets of the source videos appear as inserts. Their purpose, according to their artist statement, is to exalt the human voice, in song, and the human body, in dance, as “a political act of embodiment and becoming in a moment marked by various forms of violence against entire living fabrics.” The artists write that “regimes of power . . . have rendered them uncounted, inaudible,” but these people the artists found on the internet knew they weren’t really invisible, they were as real as anyone, and they recorded themselves to be seen and heard by other just-as-real people.

The first part of the project, Postscript: after everything is extracted, was published online in December 2020—as part of Dia’s Artist Web Projects series—and then updated in March 2022 with Part 1: May amnesia, which includes an index of 176 of the found video clips. In both these online chapters, a sequence of screens collage together the collaboratively made videos; sound files transmitting the new electronic compositions; and text files (in English, with Arabic translation) authored by the artists as well as journal articles and book chapters by others. There are also clips of trembling computer animations, digital re-creations of watercolor sketches. These frames variously pop up, overlap, fade away. One of these screens ends in silence, with a single video left to linger, against a lurid purple background. In it a circle of men are dancing, in Gaza, their legs kicking in unison to a rhythm we can’t hear, again and again, like the phantom beat will never stop.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar. © Museum of Modern Art.

At the Museum of Modern Art, the next part of May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth is now on view: Only sounds that tremble through us, which remixes the web-based materials into a thirty-five-minute sound and video installation that consumes the darkened studio space on the museum’s fourth floor. Where the website can feel informal and intimate, like a bulletin board with ideas pinned to it, the installation is polished and stylish. There are three different projections (a fourth, onto the alcove in the back of the studio, mirrors the central video opposite it); the ones beaming onto the left- and right-hand walls are slanted so they are distorted into trapezoids. In front of each are flat, vertical, obelisk-like boards, rectangular and square, tall and low, that interrupt and seemingly multiply the streaming images.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar. © Museum of Modern Art.

As videos flow across the room, texts rendered in the artists’ characteristic sans serif typeface flicker in and out in concert with the music and the performers’ gestures. They’re like poems, or song lyrics. Sometimes they provide narrative clues (noting it’s 4 am, for instance, at the Dead Sea), but they’re mostly elliptical, atmospheric, setting a tone. We’re in the lack, we’re in debt, we’re in the negative (here, the videos flash into the negative too, colors inverted, silhouettes of dancers in electric purple and green), we mourn and we mourn, here at the sea that is dead, we catch our breath and we hold it, we lose our breath, our voices tremble, we are in the tremble. As visitors read, and watch, two enormous subwoofers send pounding bass lines oscillating into their bodies. The images flash and compel, but the music is at the heart of this installation, which also functions like a listening party.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, still from May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2020–ongoing. Courtesy the artists.

Philosopher Vilém Flusser explains in his idiosyncratic 1991 taxonomy of gestures that listening to music requires intense concentration—not just of the ear or mind, but of the whole body, because the body is permeable to sound waves, which penetrate it through the skin. Skin normally separates the individual from the world, but in the act of listening to music, it becomes a conduit between the two. This, Flusser writes, “is the gesture of ecstasy.” And it is the gesture, he says, of total empathy between the listener and that to which she listens.

Flusser wasn’t one for toe-tapping, so he doesn’t go into the gesture of dancing, which would be the next logical step in his argument, because once sound waves get inside of us, seizing control of our heartbeats, they induce us to move. When we dance together, it’s not just our skin connecting us to the outside world; we also become joined to others in breath, in touch, in the mingling of sweat. Dance, too, is a gesture of ecstatic empathy.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, still from May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2020–ongoing. Courtesy the artists.

Against May amnesia’s images of celebratory dance, the text is tonally dissonant; if you were only to read this work, mourning would come through as its great theme. “we speak about / what it means to be in a constant state of mourning / every day / every day / we mourn . . .” The authors mourn cities under siege, homes demolished, deteriorating bodies, polluted water and fields, and these things are happening everywhere—they obliquely reference places from Palestine to New York, burning after George Floyd’s murder. In this regard, the work acknowledges how we are all trapped together under a regime of death, the differences being in the particularities of how we will be killed, and when. But in its imagery and in its beat, the work’s great gesture is of ecstatic empathy. If we are mourning, it seems to show, that means we’re still alive, and as long as we’re alive, there is the possibility to sing and to dance, to dream of the grand party we could have together in the glittering dark, where we will overcome our very skins and join in the world.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.