Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

In Agnieszka Holland’s tragic film about the refugee crisis at the Belarus–Poland crossing, a provocation to bear witness and reflect on complicity.

Talia Ajjan as Ghalia and Jalal Altawil as Bashir in Green Border. Courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Agata Kubis.

Green Border, directed by Agnieszka Holland, opens June 21, 2024 at Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City

• • •

To make the wrenching decision to leave your home (no matter how unendurable your circumstances may be, the choice is never easy) is to have hope—to believe that the frightening unknown for which you are departing may offer something, anything, better. Sometimes people live off nothing more than that hope—and hope is the spring from which Agnieszka Holland’s new film, Green Border, starts. Its first chapter begins in October 2021, with a family of six (grandfather, parents, three small children), cautiously cheerful, on a “Turklines” flight to Minsk, Belarus. The chatty mother, Amina (Dalia Naous), as she breastfeeds her youngest, tells her seatmate that they’re from Harasta, Syria, where brutal conflict has left them homeless for the past five years, and a deadly regime has robbed them of their most basic freedoms. They’re headed now to a relative’s home in Malmö, Sweden. “This route through Belarus is a gift from God,” Amina exults—so much safer than the treacherous crossing by sea into Europe. They are nearly there. A flight attendant passes out roses to the women passengers. “It was my pleasure to have you all on board,” the captain croons as the plane descends.

The landing marks the moment when this wellspring of hope suddenly dries and is transformed into something dark, mangled, throbbing—and we are only a few minutes into the film’s unrelentingly cruel two-and-a-half hours. Before that time is up, the family will have shrunk to four, and that abovementioned seatmate—Leila (Behi Djanati Atai), from Afghanistan, whom they welcome on their passage to cross the Belarusian border into Poland, into “free Europe”—will have disappeared. Hope swiftly becomes a putrescent relic that the desperate keep clinging to even as it pushes them deeper into punishment, danger, brutality.

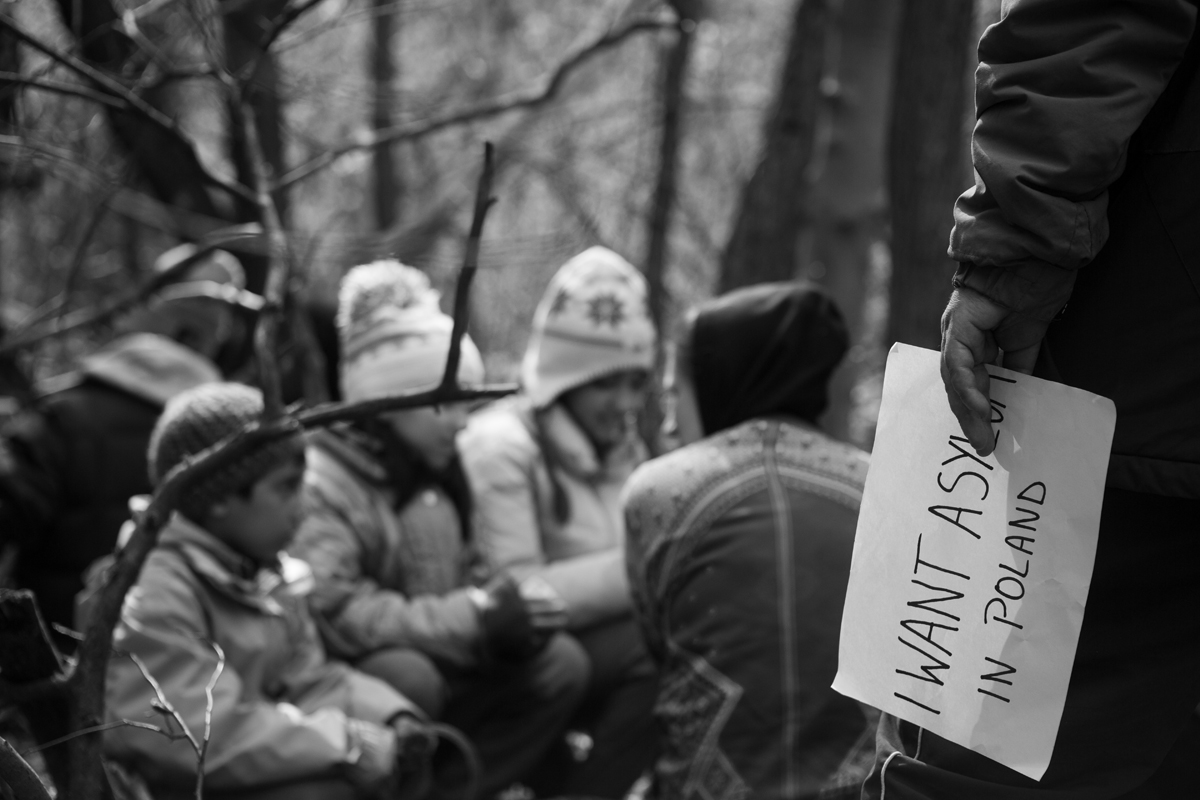

Still from Green Border. Courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Agata Kubis.

Styled almost like a documentary but paced like a horror movie—quiet pauses lasting just long enough for your adrenaline to ebb before the next episode of violence twists your nervous system back into knots—Green Border is a deeply researched, precisely detailed story (Holland has said almost every incident in the film is based on a real-life event) about the crisis at the border in the primeval forest that separates Poland and Belarus. The cataclysm had begun a few months before the film’s opening scenes, in July 2021, when Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko ordered state agencies to advertise easy passage into the EU through his land, mainly to people living in conflict-riven places like Syria, Congo, Yemen, Iraq, and Afghanistan, as a form of hybrid warfare against the NATO bloc. As refugees have surged to the forest, Belarusian and Polish militarized patrols have committed innumerable grievous human-rights abuses against them. Holland’s film, which she cowrote with Maciej Pisuk and Gabriela Lazarkiewicz, interlaces the lives of individuals on both sides of that border: Amina’s family, Leila, and other refugees who are trying to cross, and, on the Polish side, Jan (Tomasz Włosok), a border guard, and Julia (Maja Ostaszewska), a psychotherapist living in seclusion at the edge of the forest, who radically alters her life to become an activist after witnessing an unspeakable tragedy.

Maja Ostaszewska (far right) as Julia in Green Border. Courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Agata Kubis.

Green Border could be called an activist film; it is certainly a razor-sharp indictment of Polish president Andrzej Duda and his Law and Justice party’s fascistic regime. When Jan is in training for the Podlaski Border Guard Unit, his commanding officer name-checks then–Interior Minister Mariusz Kamiński and his deputy Maciej Wąsik, who insisted those seeking entry into the country were not human, but rather “live bullets” deployed by Putin and Lukashenko; twisted animals addicted to drugs; pedophiles and zoophiles who rent the children that accompany them to take advantage of “Polish compassion.” Green Border is also a crystal-clear indictment of the Western racism that allows these refugees to continue to die but eagerly seeks to aid the white Ukrainians fleeing their war-torn home, as the movie’s epilogue reveals (Poland welcomed over two million Ukrainians in March 2022). But it is also a film, in keeping with the grisaille tenor of the seventy-five-year-old director’s oeuvre—Holland remains best known for Europa Europa (1990), about a Jew who escapes the Holocaust by posing as a Nazi—of moral complexity, in which even a seeming monster like Jan has his own side of the story to tell, in which the viewer is not just asked to bear witness but to deeply feel their own complicity, to ask themselves what they would do—what they are doing now.

Maja Ostaszewska as Julia in Green Border. Courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Agata Kubis.

“How is your outrage at our reactionary regime?” Julia asks one of her teletherapy patients, Bogdan (Maciej Stuhr), whom she is treating for a benzo dependency and mild marital strife. He insists that his mental-health woes stem not from the details of his daily life but from having to live under Poland’s neo-Nazi rulers. He will turn his outrage into service to others. Julia will ask a friend, Basia (Agata Kulesza), to help, too—she assumes Basia, who votes liberal, who goes to vigils and protests, will be sympathetic to the plight of the refugees. But Basia turns away from the footage Julia tries to show her of Leila being abused by border guards: “I can’t watch that sort of thing.” She has a living to earn and a family to take care of; she can’t bring herself to help. I identified with Bogdan’s feeling of insanity in the face of our barbarous present. I identified with Basia turning away. But Green Border, with its formidable length and grueling rhythms, forced me to keep looking.

Talia Ajjan (right) as Ghalia in Green Border. Courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Agata Kubis.

At one point in the film, Jan and a fellow patroller find a body just on the Polish side of the barbed-wire border. They flip it over—it is a woman, her face frozen in a scream. They toss her over the fence back into Belarus. Later, Jan, alone in his car, listening to a pro-regime newscaster describing Duda thanking the border guards for their diligent work and professionalism, starts screaming, too, and for a second, his face looks just like hers. The image returned to mind at the film’s end, when a group of young teens—two Poles and the three West African refugees they are sheltering—sing together, in this otherwise unflinching movie’s ever-so-slight shift toward sentimentality (which risked being wince-inducing, but which I found to be a welcome reprieve), “Mourir mille fois,” by the French-Congolese rapper Youssoupha: “I cry when you cry / I pray when you pray / Your grief is my grief. . . . I’ve lost so many close to me, I feel like I’ve died a thousand times.” The great power of Green Border lies in its determined insistence on identification, on revealing this “we,” undivided—we on one side of the border, we on the other, our lives imbricated. If hope has been shriveled and distorted and maimed throughout the film, in seeing this “we,” I felt it returning to what it was at the beginning—limpid, life-giving, necessary.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.