Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

From geometric abstraction to immersive environments: the Whitney surveys the work of the legendary Brazilian artist.

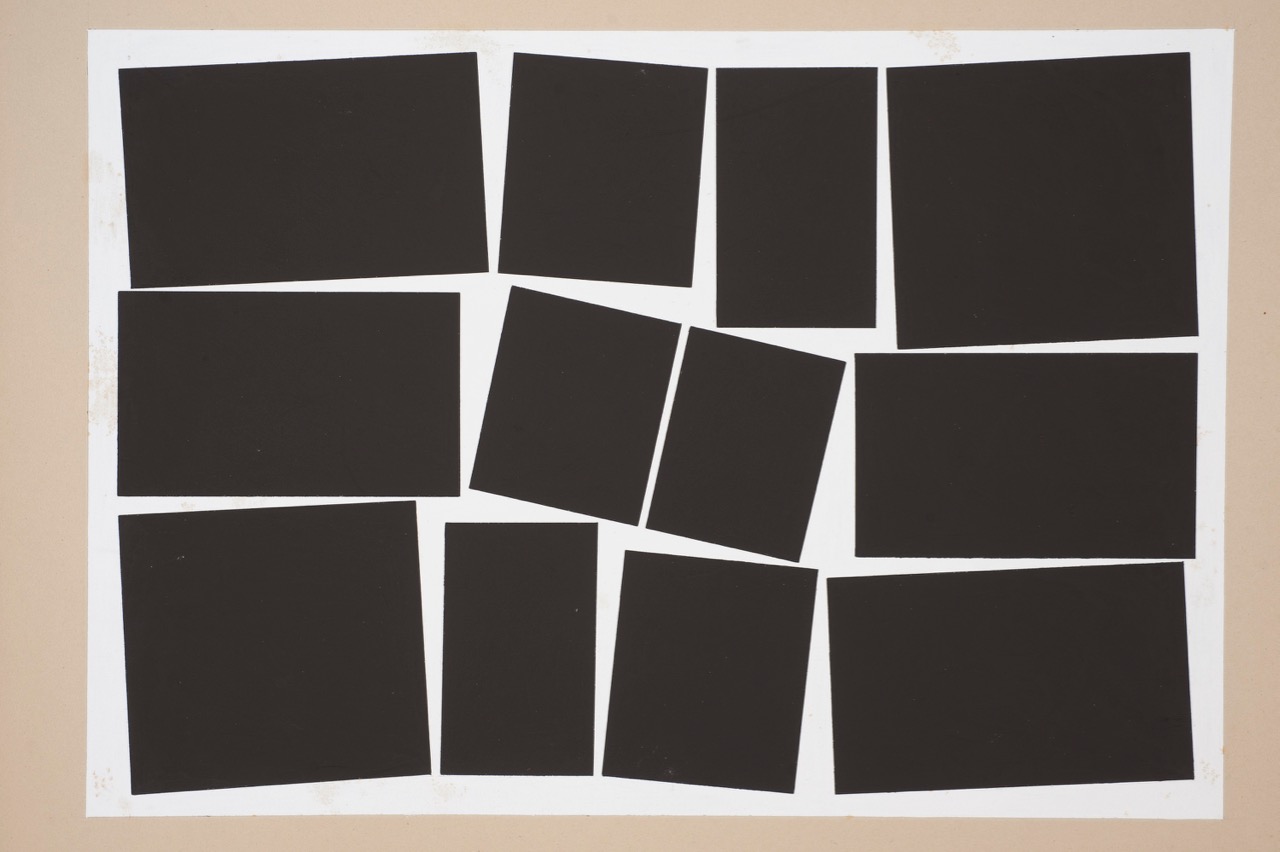

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium, installation view. Hanging sculptures, left to right: P58 Spatial Relief, Red, 1960; P52 Spatial Relief, 1960; NC6 Medium Nucleus 3, 1961–63; all by Hélio Oiticica. Image courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Matt Casarella.

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through October 1, 2017

• • •

To Organize Delirium is a traveling survey of legendary Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica—and he would have hated it. A trailblazer in the mid-twentieth-century utopian quest to collapse the division between art and everyday life, he was virulently anti-institution, disdainful of the convention of the retrospective, and tensely controlling over the presentation of his work, which was often interactive and site-dependent. The curators, of course, are well aware of this fact. Essays in the exhibition catalog meditate at length on how to cope with the many losses that haunt the project: the loss of the artist, who might have warmed to the endeavor (Oiticica died in 1980 at the age of forty-two); the loss of over 1,000 of his works after a fire in 2009; but also the more global loss that always occurs when something that was once so keenly alive becomes a static piece of history. Oiticica’s Argentine contemporary Julio Cortázar once wrote that museums are cemeteries—and there is no curatorial strategy that can resuscitate art from history. So what’s the better alternative: to refuse to present or recreate the work out of respect for Oiticica’s principles, turning his practice into something that is read about but never seen; or to acknowledge the loss and show the work anyway, in the hopes that some new propositions may continue to unfold?

I was conflicted about the answer to that question before I saw the exhibition, which debuted at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, stopped over at the Art Institute of Chicago, and is now finishing up at the Whitney. Oiticica was an artist I loved but of whom I had no first-hand experience, and I imagine that many other visitors will also be encountering his work in the flesh for the first time. It is infrequently shown in the US; this is Oiticica’s most comprehensive museum survey to date. And I’m consistently bothered by the curatorial snake oil of staging these types of vexing dilemmas front and center, as if by directly pointing to the issue the organizers can recuse themselves of the responsibility of solving it.

Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema 362, 1958. Gouache on paper, 19 ½ × 26 ¼ inches. Image courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art.

But a potential critique of the institutional framework begins to seem petty upon confronting the art: it is stunning. The exhibition starts at the beginning, with Oiticica’s friendly formalist paintings on paper and cardboard from the 1950s. Take Metaesquema 362 (1958)—stacks of variously sized black rectangles tilt at different angles, as if excitedly jiggling in place, cheekily resisting the dogma of the grid. Or another work from the same series, Metaesquema 4066 (1958), where the outlines of trapezoidal shapes in bright, primary red and blue huddle in the center of the composition, verging on the higgledy-piggledy but still gently restrained by an ineffable geometric order; the warm and cool colors create the impression of a pulsing constellation. On one hand, these early pieces are conceptually sophisticated explorations of surface and frame, form and color; but they’re also the most endearing geometric abstractions you’re ever likely to see, and no art historical knowledge is required to enjoy them. Surrounding the paintings is a roughly contemporaneous series of sculptures. Suspended from the ceiling like Calder mobiles (though some hang close to the floor), these constructions bring the 2-D geometries into the third dimension. The pale Bilaterals look like bits of Malevich paintings that floated off the canvas; the colorful Spatial Reliefs make you feel like you’re inside one of the Metaesquemas. As you walk around them, they all unfold in your vision like huge origami constructions. Though it’s tempting to rush through the first galleries to experience the more-famous environments, this work merits time.

Hélio Oiticica, Tropicália, 1966–67. Image courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Matt Casarella.

And restagings of the best-known of those environments, Eden and Tropicália, are installed side-by-side just around the corner. By the late sixties, Oiticica had abandoned image production in favor of engendering sensorial experience. Eden (originally created for Oiticica’s first solo show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 1969) is, in the artist’s words, “a proposition for behavior” that comprises a sandy beach dotted with tent-like structures where you can lay down and listen to breezy music, step into a shallow pool of cool water, enjoy a sit on a pile of fragrant hay—in short, it is an undirected invitation to laziness. The wildly influential Tropicália (first shown in the ground-breaking New Brazilian Objectivity exhibition at Rio’s Museum of Modern Art in 1967), on the other hand, is more pointed in its sociopolitical critique. Here, a path of pebbles leads you through lush potted plants, stones graffitied with bits of poetry, and an enormous metal cage housing two plump parrots that were busy devouring some snacks when I visited. Made in the midst of a military dictatorship, when notions of a “national art” were sharply contested, the environment functions as a multilayered commentary on cultural conservatism and stereotypes about Brazil. But at the same time, Tropicália transcends its political valences in its creation of a space that tenderly embraces the viewer.

Oiticica continued creating participatory environments when he moved to New York City in 1970 (he would return to Brazil in 1978, just two years before his untimely death). Typically glossed over as a fallow period, his time in New York is explored in depth here with a cornucopia of facsimile copies of his writings (the originals were mostly destroyed in the devastating fire), as well as a presentation of his (often sexy) experimental films—and, most notably, the delirious Quasi-Cinemas. Begun as a collaboration with Brazilian filmmaker Neville D’Almeida, these fully immersive, multi-channel slideshows of pop stars and “coke drawings” (which are exactly what they sound like) play alongside rock music and Latin American tunes. Viewers swing in a hammock (as in CC5-Hendrix War, 1973), or lounge on a pile of pillows and file their nails (Cosmococa 1: CC1 Trashiscapes, 1973). Oiticica would orchestrate the cocoon-like viewing parties in his dingy East Village loft; these (imperfect, as the curators admit) recreations are based on his carefully detailed and poetic notes.

Hélio Oiticica, CC5 Hendrix-War, 1973. Thirty-three 35mm color slides transferred to digital slideshow, sound, and hammocks. Image courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Oto Gillen.

Even the eminently weird conceptual artist Vito Acconci was weirded out when he saw Oiticica’s Nests at MoMA’s 1970 Information exhibition. Only visible in the current show through documentation, the Nests were a series of wood-framed cells shrouded with drapes that viewers could crawl into and indulge in whatever behaviors they chose. Now, we take immersive, participatory museum experiences for granted, and are well-trained in how to interact with them: obey the signs telling you what you can and cannot touch, obediently stand in line until a gallery attendant tells you it’s your turn to walk through the installation, apologize to the other attendant who is diligently sweeping up the sand you’ve tracked through the gallery. I left To Organize Delirium feeling deliciously mussed and rumpled, but also a little ashamed that I had gotten some cheap bourgeois thrills rolling around in a nest of foam blocks or idling in a hammock when Oiticica’s ambitions were so much grander—to create an opportunity for communion, to radically alter perceptions, to engineer small oases of utopia in a dirty world. Maybe more than anything else, that is the greatest loss foregrounded by the exhibition—the loss of our collective capacity to imagine utopia in the first place. But despite the melancholy fostered by such realizations, and despite the polite constraints of the museum, Oiticica’s work still triggers at least some sort of illusion of joy. That’s something I haven’t felt in an art space in years.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns. From 2011–15, she was the chief curator of Townhouse, a nonprofit contemporary art space in Cairo, Egypt; she was also a founding editor of Mada Masr, Egypt’s premiere platform for independent, progressive journalism. She is a recipient of a 2016 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.