Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Abstract pioneer or mystic message-bearer: a Guggenheim survey resparks debate over the enigmatic Swedish artist.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © 2018 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, the Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through April 23, 2019

• • •

“Af Klint is simply not an artist in their class, and—dare one say it?—would never have been given this inflated treatment if she had not been a woman.” This was Hilton Kramer’s assessment of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) after seeing her work in the 1986 exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985—the first time af Klint’s turn-of-the-century abstractions were shown since her death.

Kramer was angry that the exhibition was trying to put her on the same level as those manly pioneers of nonobjective painting, Kandinsky and the gang, but thankfully no one listened to him. He did, however, in a twisted and sexist way, put his finger on a certain ongoing problem of af Klint scholarship: curators and art historians have been rushing in to save her from patriarchal erasure by claiming her as the very first painter of abstraction, a woman who beat the boys by a good five years. But af Klint, an occultist, was crystal clear about her intentions: her paintings were crucially important documents of, and portals to, another plane communicated to her by spirits, not an artistic program of nonobjectivity. She compulsively recorded and annotated the work in notebooks (more than 26,000 pages worth) to ensure it would be read in exactly the right way after she was gone. (In 1932, she decided the world was unready for her message and marked in her notes those paintings that were not to be seen until twenty years after her death.)

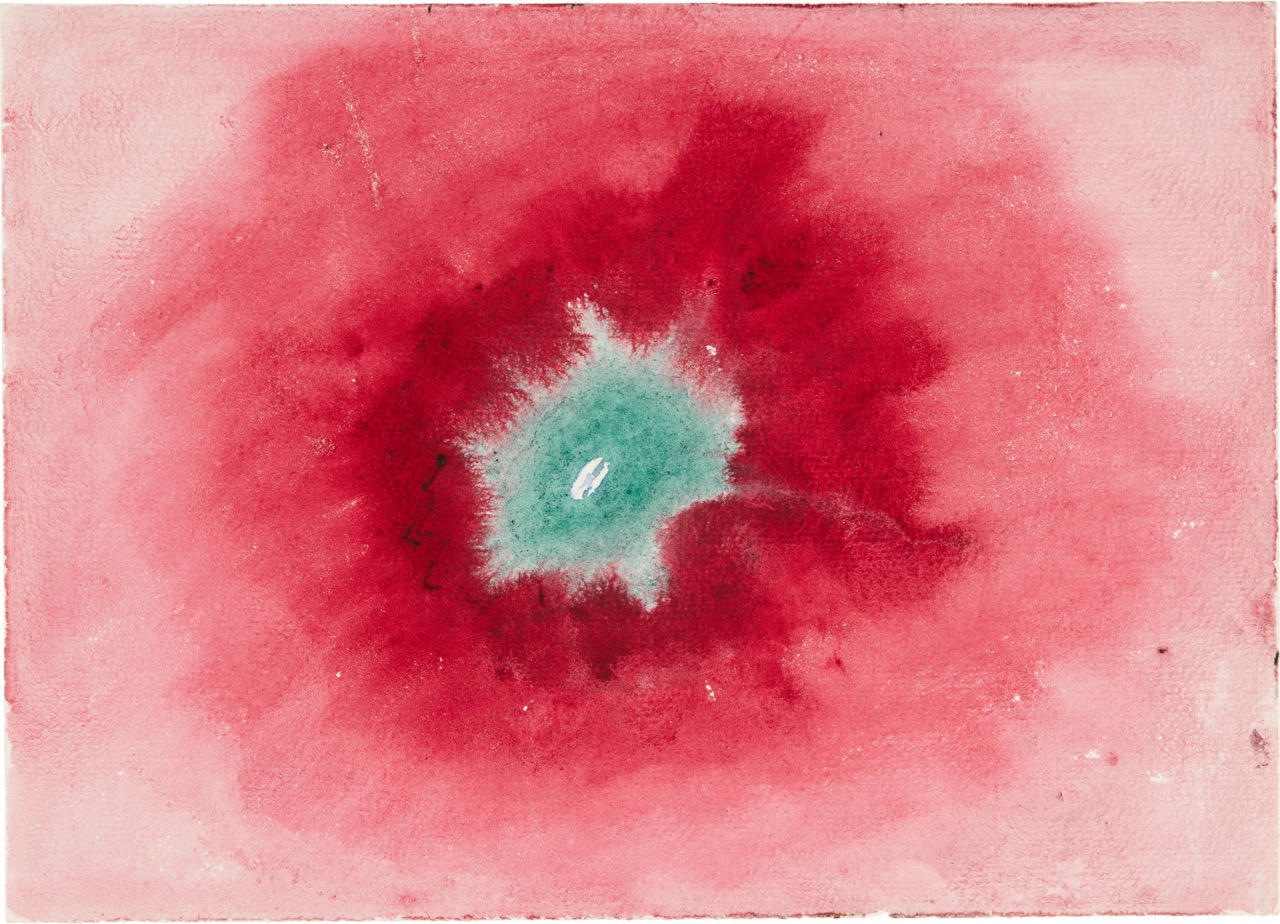

Hilma af Klint, Untitled, 1920. From On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees. Watercolor on paper, 7 × 9.8 inches. Photo: Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet.

But is af Klint’s running in the historical horserace toward abstraction the most important thing about her? At the press preview for the Guggenheim’s sweeping survey, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, curator Tracey Bashkoff made a heroic case for the painter as the original abstract artist—an avowal reiterated in the opening lines of the wall text framing the show. It’s a thesis other scholars and critics have advanced as well. Their motivation is eminently understandable—the category of “artist” has historically been denied many brilliant women, and it’s frustratingly unproductive to see af Klint dismissed from art history as a hysterical mystic. But this strategy of recuperation is a bit like cutting off the nose to spite the face; the work presages something greater than a litmus test of avant-garde originality.

Though she was a devoted chronicler of her art, af Klint eschewed diary-keeping, so not much is known about her personal life. But we do know that when she was seventeen, she started attending séances, flush with the spiritualist fever that overtook Stockholm after a famous medium visited. Then her little sister, Hermina, died in 1880, a trauma that seems to have sent af Klint even deeper into the beyond: she began obsessively reading a heady and syncretic mix of sources from the world’s religions; she was particularly taken with Rosicrucianism and Theosophy, whose tenets became the foundation of her paintings.

Hilma af Klint, Cress, 1890s. Watercolor and ink on paper, 5.7 × 5 inches. Photo: Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet.

Af Klint managed to sequester her private pain and burgeoning obsession with the other side; also in 1880, she commenced studies in art at Stockholm’s Technical School, where she was successful enough to move on to the Academy of Fine Arts. This socially sanctioned dimension is narrowly represented at the Guggenheim—one wall shows a captivating impressionist landscape next to minutely detailed and gorgeously rendered small-scale botanical drawings, the kind of work af Klint showed publicly and sold.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © 2018 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

It’s the artist’s private, slightly mad-sounding dimension—the churning desire to commune with spirits, to achieve holy union with the divine—that explodes all over the Guggenheim. In the first gallery, a series of ten-foot-high paintings washed with thin fields of color and splashed with swooping tendrils and swollen orbs and inscribed with mysterious cyphers imposes itself, astonishingly. These are The Ten Largest, painted in just over sixty days in 1907, with no advance sketches or preparation. In her notes, af Klint tells us they represent the four stages of life, and were meant to be “paradisiacally beautiful.”

In fact, those were the words of one of the spiritual guides who “inhabited” af Klint. While she was still painting polite landscapes at school, by 1896 she had also joined a collective of mediums called The Five, who took turns channeling words and images sent by mysterious forces. One of those spirits asked af Klint to create a major body of paintings to be housed in a divine temple. On January 1, 1906, she began a ten-month period of purification. In November, she started painting. A year and a half later, she had finished 111 works.

.jpg)

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 7, Adulthood, 1907. Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, 10.3 × 7.7 feet. Photo: Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet.

The Ten Largest represents the third series in this compressed period of frenetic activity—af Klint always worked in series, each piece carefully numbered, to be seen in an exact sequence, like stills from a film. These ten paintings (glowing with soft hues of lilac and peach and mauve and orange and blueberry, progressing from light to dark) also reveal the slippery nature of af Klint’s symbolic system during this early period. The loopy letters from the spirit language (which she decoded in neat, tidy script in her notebooks) have multiple valences. Certain formal elements (engorged flower petals and spiraling snail shells, which first germinated in the automatic drawings with The Five) are similarly amphibolous. The compositions are swirling and bombastic, ambiguous and equivocal; af Klint painted at least some of these on the floor, a wild innovation, as if she were giving herself fully over to possession.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © 2018 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

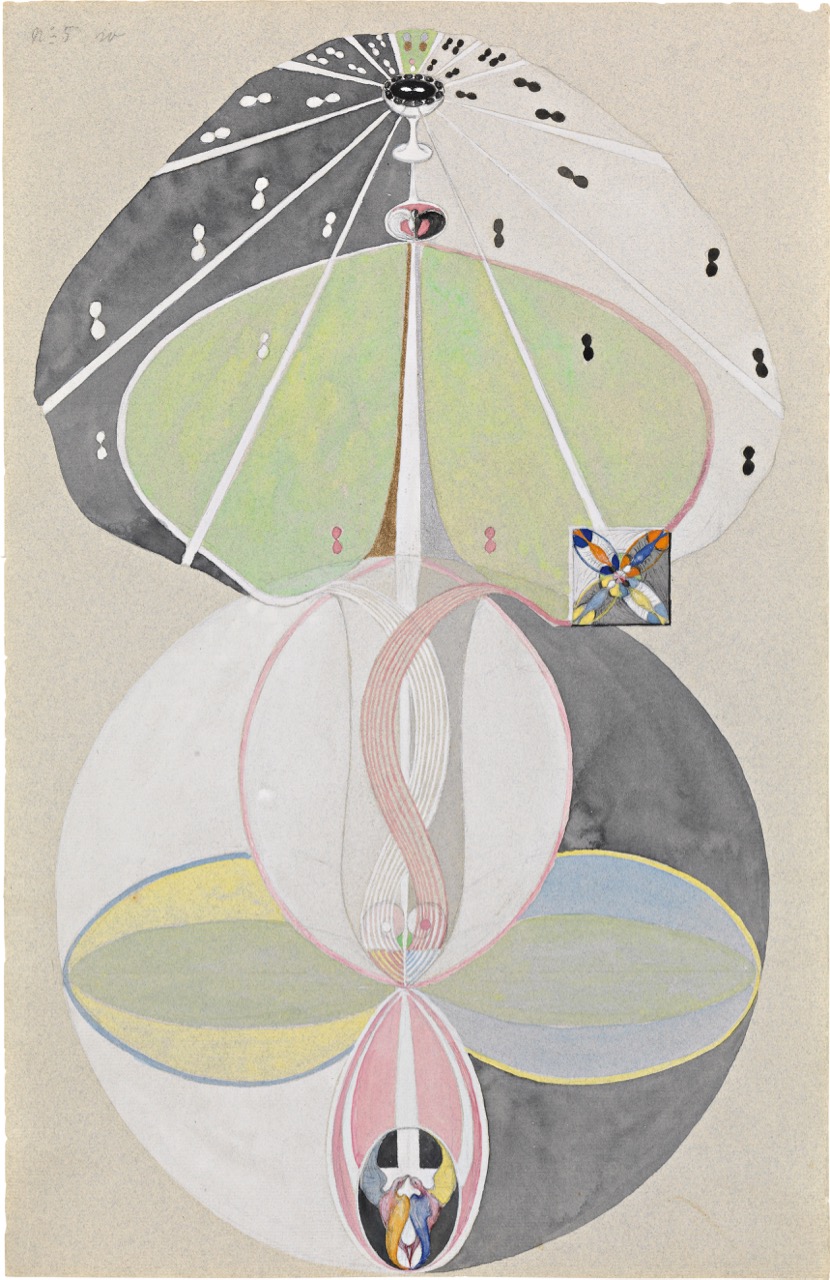

Af Klint’s “Paintings for the Temple” (totaling 193 works on canvas and paper by the time she was finished in 1915) circle up the Guggenheim’s atrium, divided into distinct formal phases. A major turning point came in 1908, when she took a four-year break (some say she was crushed by a bad studio visit with the notorious artist-hating Theosophist leader Rudolph Steiner; more pressingly, she had to take care of her mother, who had recently gone blind). When she returned in 1912, she was no longer acting as a medium, but more as an interpreter, inspired by visions. The work becomes smaller, tighter, diagrammatic. Five watercolors called The Tree of Knowledge (1913–15; af Klint’s take on the Garden of Eden) clearly draw from her background in scientific illustration, as well as a knowledge of Art Nouveau motifs and the decorative arts.

Hilma af Klint, Tree of Knowledge, No. 5, 1915. From The W Series. Watercolor, gouache, graphite and metallic paint on paper, 18 1⁄16 × 11 ⅝ inches. Photo: Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet.

The “Paintings for the Temple” culminate in The Altarpieces (1915), each almost eight feet high: a triad of ascending and descending triangles, gleaming golden spheres, six-pointed stars, dynamic spirals that spring into the viewer’s plane. The paintings wouldn’t be out of place in a Jodorowsky movie; they’re talismanic, vibrating with hidden mystical meaning. Meant to occupy the center of af Klint’s dreamed-of temple, they represent the enduring evolution of the entire cosmos, the triumphant union of dualities.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © 2018 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

What is lost when af Klint’s champions try to complicate her own beliefs about her work? The Guggenheim’s excellent, argumentative catalog reveals anxiety over this problem, with some contributors downplaying her mysticism. (How seriously should we take that medium stuff anyway, Helen Molesworth asks.) Elsewhere, sources have tried to recast af Klint as a genderqueer feminist using Theosophy as a cover for her ground-breaking artistic practice. But to rewrite af Klint’s concerns as allied with our contemporary ones is to lose an element of the works’ power. Surely her paintings can stand as the stunning monuments to conviction, to utopian belief, that they are without downgrading them to something lesser than art. That ability to imagine a beyond seems to have slipped away from us in the present. Af Klint thought the world wouldn’t be ready for her message until twenty years after her death, but maybe now it’s too late.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.